Samuel Shimon: "Banipal is a platform for dialogue, mutual understanding and knowledge of cultures"

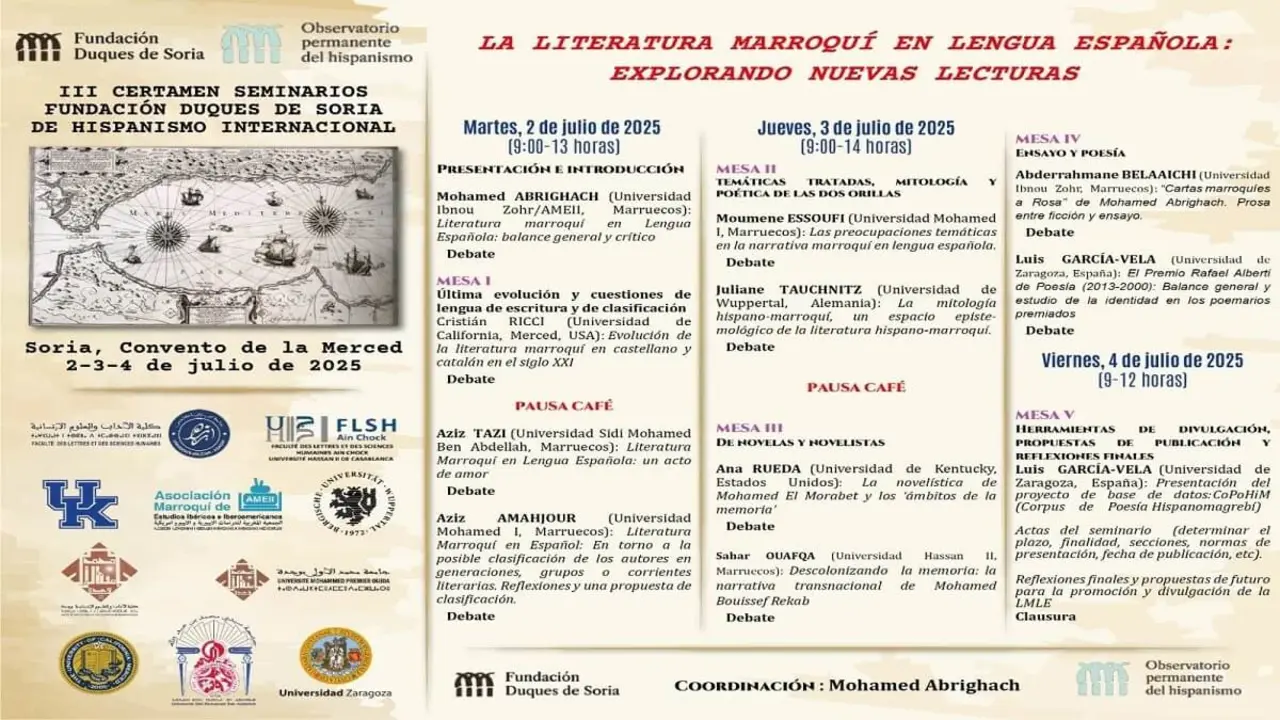

The life of Samuel Shimon could be the plot of a novel. Born into an Assyrian family in the Iraqi city of Habbaniyah, he decided to leave his country when he was just over 20 years old. The year was 1979. Amman, Beirut, Cyprus, Egypt, Yemen... these are some of the places where he lived until 1985, when he was granted asylum by the French government. Complicated years, full of experiences, some good, some not so good, but during which he never lost his passion for books and his desire to make Arab literature known. A journalist, writer and editor, his first writings appeared in the 1970s, although it was not until 1987, in Paris, that he published his collection of poems in Arabic, Old Boy. France was also the country where he set up his publishing house Gilgamesh with the aim of promoting Arab writers, and which inspired his first novel, An Iraqi in Paris, which was published in 2005 by the Dar Al-Jamal publishing house in Beirut. The book was a bestseller in the Arab world and was translated into several languages: English, French, Swedish, Hebrew and Kurdish. His next novel may soon be published: The Assyrian Fedayeen, in which he delves into the Palestinian resistance in Beirut to tell us what he lived and felt.

And from France to England. It is here, in London, that he meets the researcher, translator and editor Margaret Obank. His life changes again, both personally and professionally: they unite their love and their determination to make his great literary dream come true. Together they published the magazine Banipal, named after the emperor Ashurbanipal (668-627 BC) who founded the first library in the world, translating Arabic authors into English; in 2004 they set up the Foundation of the same name to "make modern Arabic literature known through translation"; and they created the Saif Ghobash-Banipal Prize for the best translation from Arabic into English.

In the middle of the pandemic, in the summer of 2020, Samuel Shimon and Margaret Obank decided to go one step further: the publication of the magazine Banipal in Spanish, which they consider "a platform for dialogue, mutual understanding, tolerance and knowledge of cultures". Now, the effort of both is to make Arabic-language writers known to Spanish-language readers. Samuel Shimon told Atalayar: "Spanish publishers should take a look at the published issues of Banipal to discover the treasures of modern Arabic literature".

A new issue of Banipal magazine has just appeared, named after Assurbanipal, the last great king of Assyria. You are an Iraqi of Assyrian origin, can you tell us the story?

Banipal magazine is indeed named after the emperor Assurbanipal (668-627 BC) who was the founder of the first library in the world. That library, which had a catalogue and was perfectly ordered, contained thousands of tablets containing the intellectual and cultural production of the Mesopotamian civilisation in all fields of knowledge. In the same way, Margaret Obank and I wanted to found a magazine in the image of that library, with texts in prose and poetry by authors from all Arab countries between its flaps. Indeed, we have succeeded in fulfilling our dream over the course of a quarter of a century, as evidenced by Swedish scholar Tetz Rooke's statement that "Banipal magazine is both a beautiful library and a bibliographical gold mine for anyone interested in contemporary Arab literature". Or as the well-known Lebanese poet and critic Abbas Beydoun described it as "the best current encyclopaedia of Arabic literature, which with its texts, photographs and essays is like a comprehensive library". The celebrated translator Humphrey Davies also said: "My collection of back issues of Banipal is to me like the library of Alexandria, giving me an idea of what is going on in the literature of the world of Arabic writing".

Banipal was born to become a new kind of library: a library for contemporary literature from the Arab world and its diasporas, a journal in permanent connection with the Arab literary scene that aims to make Arab literature accessible to the widest possible audience, placing its literary production in its rightful place in world literature.

This magazine for the dissemination of Arabic literature was born in 1998, a project with your wife, with translations from Arabic into English. What motivated you, in 2020, to make a Spanish version?

In 1998 we decided to bring out the English version of Banipal magazine as a response to the great lack of translations of Arabic literature into English, as well as for three other reasons: the first was that Arabic literature is part of global culture and human civilisation; the second was to deepen intercultural dialogue; and the third was the sheer enjoyment and knowledge that comes to the reader from reading good poetry and creative texts. These same three reasons are at the basis of the publication of Banipal magazine in Spanish, which we intend to be an open window through which "the breeze of the soul and the conscience of the Arabs" can enter, so that the Spanish-speaking reader has the opportunity to approach the rich production of the Arab literary scene on a regular basis and thus bring this production out of the state of isolation in which it has been plunged. The Spanish version of Banipal is a platform for dialogue, mutual understanding, tolerance and knowledge of cultures, which aims to establish a base of readers who love and value Arab literature.

The magazine has helped to translate and publish the work of hundreds of writers, both emerging and established, who had not previously been translated into English and Spanish. Banipal has also organised, on its own or in collaboration with other organisations, literary events and tours of Arab writers to numerous cities in the UK and Spain, as well as to New York, Dublin, Berlin and Guadalajara, Mexico. In addition, the Banipal Foundation for Arabic Literature was established in 2004 to "raise awareness of modern Arabic literature through translation" and, in 2005, we began awarding an annual prize to promote literary translation from Arabic into English under the auspices of the Society of Authors in the UK.

Translations from Arabic into Spanish and vice versa are very few. Given our history and proximity to Arabic-speaking countries, why do you think this is the case?

I believe that ignorance and carelessness are among the most important factors impeding the translation movement from Arabic into Spanish. The Spanish publisher does not know the Arabic language and therefore does not want to embark on an economically costly and uncertain adventure. On the other hand, it must be said that Arab publishers do not bother to offer summaries translated into English or Spanish of their new publications. At international book fairs, I meet cultural institutions from Denmark, the Netherlands, South Korea, Poland and other countries that do offer translated summaries and excerpts of their new novels, as well as information in other languages about their published children's books, etc.

The catalogue of translations of Arabic literature into English when we started Banipal magazine was no better than the current catalogue of translations from Arabic into Spanish and, for example, no translations of any collections of poetry by great Arab poets such as Adonis, Mahmoud Darwish and Saadi Youssef had been published. Banipal magazine, in its English version, has played a major role in improving translation from Arabic into English. We used to send about 200 free copies to English and American publishers, as well as to many world-famous writers. I will tell you an example: once when we dedicated a special dossier to the Lebanese writer Hanan Al-Sheikh, she called me and told me that Salman Rushdie (they have a strong friendship) had phoned her and told her that he had read the special dossier dedicated to her by Banipal. She said, "I didn't know Salman Rushdie bought Banipal magazine!" and I told her we were sending it to him as a gesture of appreciation. We kept many letters from world famous writers who used to read the magazine.

In 1998, Margaret met the late Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz and gave him a copy of the magazine. He jokingly told her: "Have you waited until I'm eighty to publish this magazine? You should have started much earlier"

The existence of a magazine that specialises in translating excerpts of modern Arabic literature into Spanish and that closely follows the Arabic literary scene is something that fills a gap and that over time will undoubtedly have a readership base. After all, it is our responsibility to encourage the translation of Arabic literature into Spanish.

Issue 10 is dedicated to Saudi Arabia, with 27 authors and 3 literary critics. What would you highlight from this special issue?

We have devoted issue 10 of the Review (summer 2023) entirely to "Modern Literature in Saudi Arabia" with the intention of offering a panoramic view of the schools and trends of this literature in the novel, the short story and poetry. It presents a selection of excerpts from the most outstanding works in these three disciplines, preceded by a preliminary critical study, signed by leading writers and scholars, on the production and characteristics in each of them. This issue is undoubtedly an essential source of reference for scholars and readers in Spanish who want to take a look at the current Saudi literary scene and discover valuable examples of its creative world. The novel includes translations of excerpts from nine novels by writers who have enjoyed success in Arabic, and not only in Saudi Arabia, including Raja Alem, Yousef Al-Mohaimeed, Mohammed Hasan Alwan, Omaima Al-Khamis, Badriya Al-Bishr, Fahd Al-Atiq, Fatima Abdulhamid, Yahya Amqassim and Laila Al-Johani. The short story section features numerous stories by writers of the new generation who have been published since 2020, such as Walaa Fahad Al-Harbi, Ahmed Al-Jumayd, Somaya Al-Sayed, Wafa Al-Rajeh, Aminah Al-Hassan, Shada Al-Quraishi and Mansour Al-Ateeq. As for poetry, poems by Ghassan Al-Khunaizi, Ashjan Hindi, Fawziyya Abu Khalid, Ibrahim Al-Husain, Ali Al-Domaini, Hilda Ismael, Ibrahim Zooli, Mohammad Al-Domaini, Abdullah Thabit and Mesfer Al-Ghamdi who are all recognised on an Arab level are advanced.

The novel is considered the fastest growing literary genre among Saudi authors. According to the critic Ali Zaalah, the total number of women novelists before 2000 was no more than twenty, while in the last decade there have been more than thirty Saudi women novelists, a figure that is close to the current number of male novelists. The interest in the novel is mainly due to the political stability and the economic and demographic growth that Saudi Arabia has experienced, and to a lesser extent to the cultural openness to Arab and international literary production. Literary critics specialising in the Saudi novel point out that the real rise of the novel occurred in the 1990s due to factors emanating from within Saudi society and others from abroad, which created a climate conducive to the production of a modern novel in form and content, in a social environment that was ready to receive a novel capable of penetrating the depths of a self that had hitherto been veiled by fear of traditions and all kinds of real and imaginary restrictions.

What do Saudi writers now bring to the Arab literary scene?

The Arab literary scene has changed with the advent of the internet and it is no longer difficult for readers in Morocco or Sudan to access texts by Iraqi or Yemeni writers. There is a famous Arabic saying: "Egypt writes, Beirut prints and Iraq reads". This statement has become in the eyes of many not only incorrect, but also labelled as "racist". In the last quarter of a century things have changed a lot and the famous printing presses in Beirut are no longer the only ones publishing books, but there are many publishing houses in Baghdad, Casablanca, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Sudan, in almost all Arab countries, and thanks to the Internet and social networks it is very easy for the Iraqi reader to keep up with what is being written in Sudan.

Saudi literature is an essential part of Arab literature and the presence of Saudi writers in the current Arab literary scene is almost equal to that of their counterparts in Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon and Morocco, in some cases even dominating the current Arab literary scene, especially in the category of fiction. Proof of this is that the largest number of novelists who have been finalists or winners of the most important Arab literary prize, the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, known in the Arab world as the 'Arab Booker', since its foundation until today, are Saudi authors.

Let's talk about you. You are an editor, but also a writer. Your first novel, An Iraqi in Paris, was a great success. Now you are preparing The Assyrian Fedayeen, which recounts your experience in the Palestinian resistance in Beirut. It will be published almost 20 years later...

I hesitated a lot when writing this novel because it touches on many sensitive issues, whether it's the Palestinian cause or the lives of many people I met during that period. I started writing it in 2010, and I could have finished and published it before 2012. But, as I said, I hesitated and backed off when I realised that sex was an overwhelming element in the unfolding of the novel's events and that it could somehow cause me a lot of problems. The English title I chose for the novel is Underwear Underwar which perfectly expresses the content of the novel. Another thing I might add here is that most novels dealing with the Lebanese civil war bear the mark of some of the confessional premises of the authors of those novels. The hero of my novel, a young Assyrian named Sankhiro, narrates the events of the novel with an honesty that borders on naivety. This is, after all, the same style in which I wrote An Iraqi in Paris, which was the main reason for the book's success.

Besides reading Banipal magazine, do you recommend any Arab writer, a book you are reading now?

I recommend reading two novels: the first is A Country Without Heaven by the Yemeni writer Wajdi Al-Ahdal, published in its entirety in the new issue of Revista Banipal and translated by María Luisa Prieto. The tragic-police novel A Country Without Heaven is set in a conservative environment in the shadow of severe tribal traditions that imprison women and make them pay dearly for their femininity. Wajdi al-Ahdal captures with astonishing skill the repression and hardship that dominate the society, through the emphasis on the action of how men "watch" and "observe" women. Sama, the character around whom the narrative revolves and whose sudden disappearance forms the main plot of the unfolding events, says: "The incessant stares of dozens of passers-by get on my nerves, get on my nerves and stress me to an unbearable degree. I consider these intense stares coming from all sides to be a pernicious type of male violence". These stares come from all men in society, including a young neighbour who is not yet sixteen and whom Sama treated with affection, taught him and helped him with his homework.

Unfortunately, the second novel has not yet been translated. It is The End of the Desert by the young Algerian Saïd Khatibi, which won the Sheikh Zayed Book Prize in the Young Literature category. In issue 11 of Banipal magazine we will publish an excerpt from this novel translated by Salvador Peña Martín. The beginning of the narrative resembles a detective novel. There is a crime: someone has murdered the artist Zakía Zaguani, nicknamed Zaza. The discovery of the body in a marginal neighbourhood of the city by a poor shepherd opens an investigation to find the perpetrator of the crime. Two intertwined hypotheses are put forward: the one defended by Hamid, the policeman in charge of the case, and the one put forward by Noura, the lawyer of the accused as the first suspect in Zaza's murder.

However, it would be reductionist to categorise this novel as just another unsolved crime. It is set in Algeria in the late 1980s, on the eve of the great changes and the beginning of the Black Decade, and the crime story is only one of the many layers that clothe the novel. Khatibi splendidly portrays the environment in which people's relationships develop: the tragedies, the hopes, the economic situation and the psychological responses of the characters. The novel also touches on socio-political problems such as the lack of medicine and food, water shortages and demonstrations. Furthermore, The End of the Desert depicts how the leaders of the war of liberation stole and accumulated wealth, as well as denounces the monopoly they held on all basic commodities. At the same time, it narrates the rise of a wealthy bourgeois class, which it contrasts with a poor class living in slums and half-destroyed houses.

Let's finish this interview. How do you want to do it?

Finally, I would like to suggest to Spanish publishers that they take a look at the published issues of Banipal to discover the treasures of modern Arabic literature.