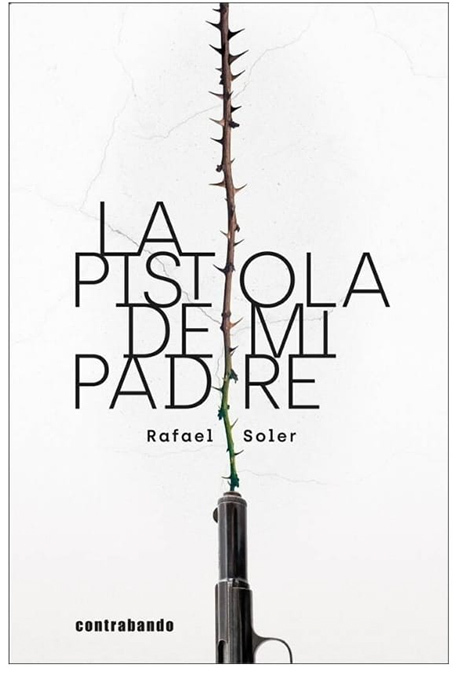

Soler: ‘My father's gun is perhaps the conversation I never had with him’

‘Where does this way of writing novels come from?’ asked the writer Luis Landero before stating: ’It is radically original, unpredictable in the plot, in the characters, in the literary resources used...’ He was talking about Rafael Soler and his freedom when it comes to writing. Both of them had an interesting conversation at the Madrid headquarters of the General Society of Authors and Publishers (SGAE) on the occasion of the former's latest novel: La pistola de mi padre (Editorial Contrabando).

A long silence

A meeting, the two of them, as if no one were listening. The two of them and their confidences; the two of them and their curiosities; the two of them and their complicities; the two of them and their languages; the two of them and their memories and their fears and their frustrations. The two of them. And so, in the conversation between these two writers, in which they didn't need to tell each other that they admired each other because it was palpable, we learned why that young writer Soler was who showed promise, who was on the list of the good ones, who had already written novels such as The Scream (1979), The Heart of the Wolf (1981), The Dream of Torba (1983) or Ravine (1985), who rubbed shoulders with the leading writers of the moment, great writers today, one day disappeared, and did so for many years. ‘I realised I didn't have the talent for a literary life,’ Soler said. But maybe that statement wasn't entirely true, because that itch was always there, because eventually the day came when Lucía, his wife, didn't hesitate to tell him it was time, ‘that he had to go back to his own kind’. ‘And I went back to being a poet,’ says the Valencian writer.

And so it was, because after that long silence it was poetry that put Soler back on the list of writers whose names had been fading away. His work was entitled Maneras de volver (Ways of Returning) (2009), which was followed by other collections of poems until, in 2018, the narrator Soler did indeed return, at last, with El último gin-tonic (The Last Gin and Tonic), and two years later with a wonderful story full of tenderness and humour: Necesito una isla grande (I Need a Big Island). And since then, more poetry, until now, when he bursts back in with La pistola de mi padre (My Father's Gun).

He returned, fortunately for himself, for his readers, for Lucía, indispensable in her early mornings, in her writings, in her wake-up calls, in her fierce criticism, in her marvellous walks by the sea, in her constant and profound support. He returned without a return ticket and to stay.

And among friends like him, one tells what on many occasions is difficult to tell. And Rafael Soler threw himself into the arena like a good bullfighter. And he said the ground-breaking phrase, because it does break your heart a little, because it lets sadness appear, because these are not things that are said just like that, in public: ‘I realised that, perhaps, I had written this story to have the conversation I never had with my father’. And there is a silence, and there is nothing more to add to that sentence. But that thought, that reflection came later, when the novel was already written, when many early mornings had passed, when there was already a full stop.

‘Your father wants to see you’

And this sentence comes from a question from Landero, from wanting to know where his latest novel began. And then he took us all back to that first early morning when, at four o'clock, the sentence came to him: ‘Your father wants to see you’. When he heard himself saying: ‘And what does he want now?’ When he saw his characters: father, mother, son... When he got out of bed, that morning and the following ones, ‘crazy’, says Soler, until one of them, Lucía, asked him: ‘Are you writing?’ ‘Yes’, he replied. ‘And is it a novel?’ Lucia asked again. And he said yes again. And that's how it all began. A family with a father “who doesn't speak, and that's deliberate”, Rosario, Carlos, Isabelita... A narrator to bring order, Castellón, a mattress salesman. And... you'll have to read the novel to find out what happens next.

And Landero talks about the strength of his characters, characters who are very human, And Soler agrees and tells him that he needed those four strong characters in this novel. And both delve into the curious world of those who star in stories to affirm that, sometimes, and without wanting to, a secondary character suddenly begins to take centre stage. And they also delve into the world of language, a language detested by Landero ‘when it is administrative and bureaucratic’ and Soler agrees with him, and both defend creativity and originality and from the language they approach artificial intelligence, although they pass by it half-sideways, because they do not want to go too deep into what it means and will mean, although they did make it clear that it is a complicated moment.

And there they are, having that interesting conversation as if they were both sitting at a café table, which could well be El Comercial, with its Soler gin and tonic and its glass of Landero red wine, talking about their things, their curiosities, about My Father's Gun.

‘The poet wins’

And Landero, at another point in the conversation, wants to know how the poet and the novelist get on. And Soler doesn't think about his answer for two seconds: ‘The poet wins’. A poet who says that he is happy when he writes novels, that he is very disciplined and ‘a real pleasure’. Music, coffee, a cigar, six in the morning... But faced with such effusiveness, and from writer to writer, two disciplined writers who work in the morning, Landero looks at him and repeats the word ‘enjoyment’, as if he did not quite believe in that great joy when it comes to writing, and he asks again: ‘And when things don't work out?’ And Rafael Soler opens up: ‘I am not immune to discouragement and despondency’. Laughter. And it is wonderful to witness this hand-in-hand that envelops them.

Sincere questions and answers that follow a dual path, Soler's personal and vital and the literary or perhaps it is only one that, sometimes, after merging needs to separate in order to meet again. Unfiltered questions and answers that provoke interest in those who listen, laughter at the witticisms, curiosity about what is being said, the desire to read La pistola de mi padre and also Soler's poems because of the times he confesses to being more of a poet than a novelist: ‘I am a poet who also writes novels’.

One day, he says, Lucía told him he was ‘a frustrated bastard’. And if we have to make confessions and talk about frustrations, Landero also dared: ‘If you are a frustrated bastard, I am a frustrated poet’. And between frustrations and laughter, a moving and amusing encounter came to an end with the reading of a few lines not exactly from My Father's Gun, but from Landero's The Balcony in Winter, and that first chapter entitled ‘No More Novels’. Fortunately, that title was not a portent of anything and here we are, enjoying, on this occasion the last of Soler, the poet who writes wonderful stories.