The day it all began to fall apart

With each passing day, those events seem more distant, but Pedro Sánchez's rise to power through a motion of censure, with a cheating black pudding included, was the culmination of a series of circumstances, coincidences and blunders, which ultimately led to the current political situation the country is going through.

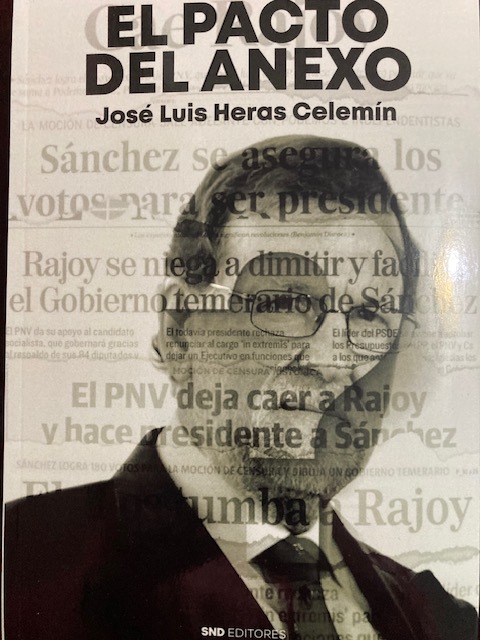

‘El Pacto del Anexo’ (SND Editores, 383 pages) is a fictionalised account of those decisive days for Spain. Its author, the Zamora-born engineer José Luis Heras Celemín, knows the corridors and undergrounds of the Congress of Deputies well. Not in vain does he work as a veteran parliamentary chronicler without wishing to stray from his fine observation of Spanish political life, a vision captured in works such as ‘El Caso Naseiro y algo más’, ‘El Caso Bankia y algo más’ and ‘El Socialismo Superado’, several of his most outstanding stories.

The vast majority of Spaniards who experienced those days live or through the news are still asking themselves questions such as: Why did Mariano leave? Why didn't President Rajoy resign two minutes before the vote and leave the government in the hands of his party? Why did he spend the afternoon taking ‘shots’ and not return to Congress? Why wasn't Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría, the vice-president, president of the Spanish government?

The book is a compilation of the most relevant facts in the author's opinion. For him it was decisive to discover the secret celebration of a meal in the small restaurant of the Congress of Deputies, the one that crosses the passageway under the Carrera de San Jerónimo. As diners, deputies from different groups were seated at the table, it seemed that they had been carefully chosen. The meal coincided with the meeting between the President of the Generalitat of Catalonia and President Rajoy, at the end of which Artur Mas summoned the national press to the premises of Blanquerna in Madrid, also dependent on the Catalan government.

‘In the novel there are events that show real powers, hidden or otherwise’, says José Luis Heras, for whom ‘in Spanish political life, these powers of all kinds influence as much as they can, although the reasons are not always known‘. This is what the (good) journalists always try to unravel, although as one of the characters in the novel confesses, ‘when we journalists go there are those who have already been there twice, some are even more ahead of us’.

The author scrutinises the veracity of clichés that are deeply embedded in public opinion, such as Rajoy's supposed laziness or his alleged disdain for finding out more than a few things. And, after collecting and contrasting dozens of testimonies, he puts it in the mouth of another character that ‘Don Mariano is very intelligent, much more so than all those in Genova [headquarters of the Partido Popular] and in the government. There are those who think he is lazy and those who believe that he only knows what he is told. He knows what it's all about, so much so that it is he who, if he doesn't direct everything down to the smallest detail, is the one who cuts and distributes the codfish’.

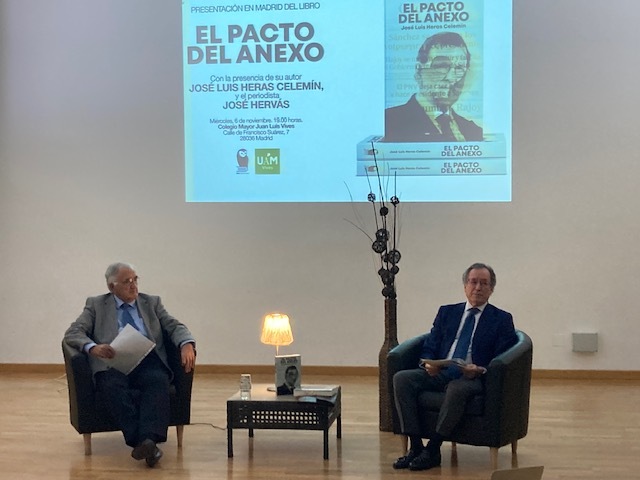

A former student of the Colegio Mayor Luis Vives, José Luis Heras chose this venue for the presentation of the novel, in conversation with a historical figure from Televisión Española, José Hervás. The latter underlines Rajoy's character portrayal with complementary information that is not to be missed, such as the revelation of a three-way meal, including President Rajoy, in which one of them asked the head of the Spanish government ‘the need to do something, to prepare a strategy to deal with the Catalan question’. According to his account, the response left him petrified: ‘Let those [Catalan] politicians drown on their own’.

At a time when the so-called political class is undoubtedly discredited, the author vindicates it after having spent a long time getting to know and analysing its members. We are in a democracy,’ he says, ’in which politicians are not extraordinary people, not even the best. Everyone does what they can, know and want to do. They are human, with virtues and defects, the latter especially exposed by the media. Their loves, horns, envy and desire for power or revenge are no different from the society in which they live or the social status of each one of them’.

A novel in which, as he himself confesses, he has preferred not to include the pages of what would have been his own conclusion, so that it is the reader who, in view of all that has been narrated, is the one who decides the ending.