Ever Given sets alarm bells ringing over new and bigger megabuqs

The Japanese cargo ship that blocked the Suez Canal is dwarfed by the new mega-ships that are coming out of Asian shipyards and which, according to experts, pose increasing risks to the shipping industry.

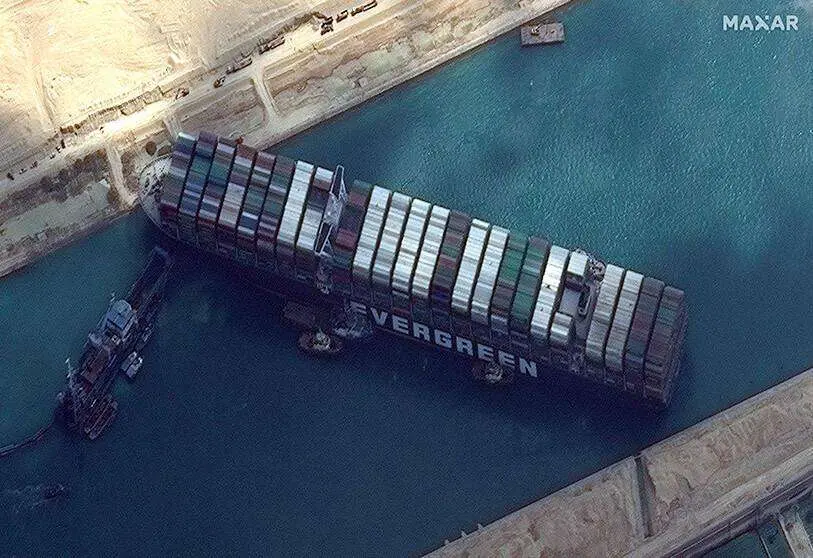

At 400 metres long and with a capacity of around 220,000 tonnes, the ship involved in the incident, the Ever Given, is just the tip of the iceberg in a sector led by Korean and Chinese companies, and whose trend is towards ever-larger sizes in line with the boom in international trade.

The capacity of container ships has soared by 1,500% since they started operating more than half a century ago. In the last decade alone, their cargo potential has doubled, according to data from the German financial and insurance group Allianz Global.

"Building ships just for economy of scale is no longer enough," Rahul Khanna, global maritime risk consultant at Allianz, tells Efe, who sees "a clear gap" between the exponential enlargement of ships and the pace at which risk mitigation measures are implemented.

South Korean and Chinese shipowners are leading this "arms race" and in 2020 shared 43% and 41% respectively of the industry's global order market, according to official data and UK consultancy Clarkson.

The five largest mega-carrier models today, mostly operational from 2020, are all of South Korean manufacture and range in capacity from 23,000 to 24,000 TEU, well above Ever Given, giving an idea of where the industry is heading.

Last January, the world's largest commercial shipowner, China State Shipbuiding Corporation (CSSC) delivered to French logistics company CMA CGM a mega cargo ship with a capacity of up to 23,000 containers, which is about 3,000 more than the capacity of the Ever Given.

The new vessel, 400 metres long and 61 metres wide, was the fifth such ship delivered to the company since September, when the Jacques Saade became, according to CSSC, the world's first LNG-powered 23,000-container freighter.

Among the dangers associated with such huge vessels are greater difficulties in the event of accidents such as fires or collisions, greater exposure to extreme weather conditions and groundings such as the Ever Given in Egypt's sea lane, according to Khanna.

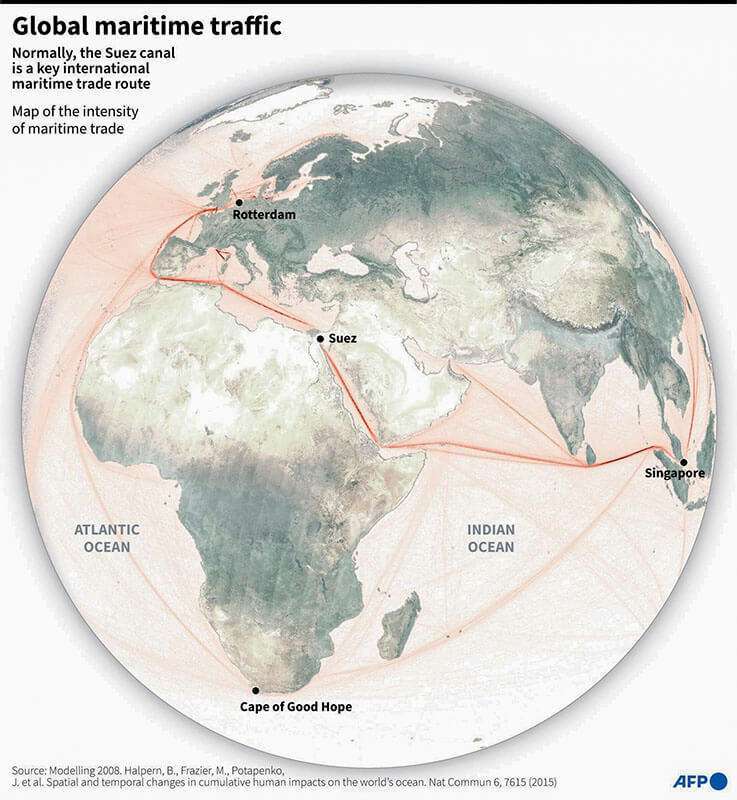

The blockade of the Suez Canal caused a daily loss of $12-15 million per day to the shipping industry, according to initial estimates, but also taught some lessons.

Ports and canals "have not always been developed sufficiently" to accommodate extra-large vessels and in some cases have become "relatively cramped" and significantly reduced "manoeuvring space and margin for error", says the aforementioned captain and maritime risk consultant.

In addition, many ports "do not have sufficient infrastructure to deal with mega-ships if something goes wrong", the expert stresses, adding that "other rescue operations for ships of this type have taken much longer than Ever Given".

The Suez crisis has opened the debate as to whether the size of sea lanes such as this or the Panama Canal could ultimately represent a limit to the size of cargo ships, and whether the necessary additional infrastructure development could undermine the profitability of even larger mega-ships.

In Khanna's view, the Ever Green incident "will not be enough to curb the growth" of these ships, which will continue to get bigger as long as risk prevention measures in infrastructure, maritime operators and shipowners are upgraded.

In South Korea, the shipbuilding industry was born in the 1970s with Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI) and its president Chung Ju-yung, an emblematic North Korean-born businessman who was one of the fathers of the South Korean economic miracle, and until the 2000s was one of the main economic pillars of the Asian country.

Its price competitiveness and its growing technical capacity to build supercarriers and supertankers have taken HHI from domestic leader to global market dominator, a position it aims to reinforce with plans to take over Daewoo Shipbulging & Marine Engineering.

These two groups and Samsung Heavy Industries had a combined turnover of 28.8 trillion won (about $25.48 billion) in 2020, and nine of the world's 15 largest supercarrier models came from their shipyards.

In the case of Chinese shipbuilders, their expansion has gone hand in hand with the country's growth as a manufacturing and exporting power in recent decades, and also made possible by state support.

Created in the early 1980s with an important component of military objectives, and sanctioned last year by the United States for its alleged links with the Chinese army, the aforementioned Chinese colossus CSSC expects to have another 400-metre mega-ship with a capacity of 23,000 containers ready this month.

According to its website, its clients include companies from Germany, Norway, Belgium, Sweden, Hong Kong, Greece, the United States, Japan and France.