Joseph E. Stiglitz: "The pandemic has accentuated the inequalities in our society"

"Each country, period, situation has a singularity that distinguishes it from the others. But there are also similarities, convergences and resonances. This is where the idea of Latin America comes from, as a concrete history and as an imagination. With these words, Brazilian sociologist Octavio Ianni spoke of a region that is currently facing one of its greatest challenges. The economic weaknesses, the social and health systems' precariousness that characterize this continent, together with the economic and health crisis caused by the coronavirus have brought Latin America to the edge of the abyss. In this context, institutions such as CAF -- a development bank established in 1970 and made up of 19 countries, 17 from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal, and 13 private banks from the region -- play a fundamental role. Since its creation in 1970, this organization has financed more than US$188 billion to bring water, electricity, housing, education, health, mobility and telecommunications to millions of Latin Americans.

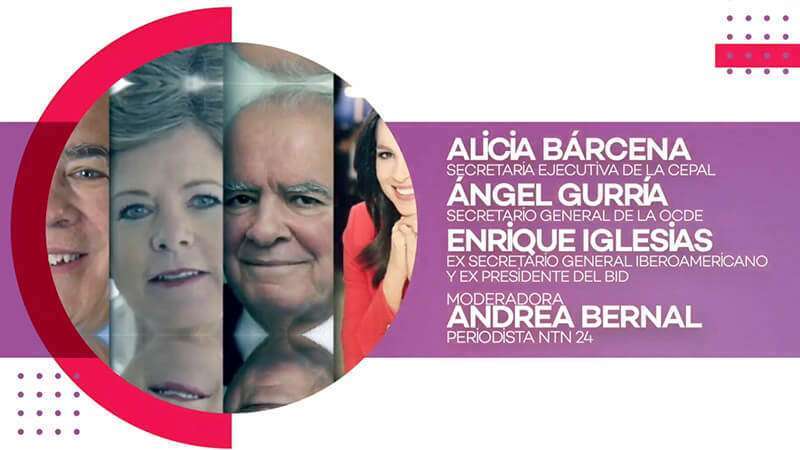

"In Latin America we have faced many adversities, some have lost much more than others, but today we understand that solidarity is a force that always accompanies us". The Latin American development bank thus began the event organized to celebrate its 50th anniversary, a webinar entitled "Keys to rethink the present and future of Latin America" in which Luis Carranza, executive president of CAF; Joseph E. Stiglitz, professor at Columbia University and winner of the 2011 Nobel Prize in Economics; Ángel Gurría, Secretary General of the OECD; Alicia Bárcena, Executive Secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC); Enrique Iglesias, former Ibero-American Secretary General and former President of the IDB; and Andrea Bernal, journalist at NTN24 and in charge of moderating this panel.

"The world will no longer be the same, but now we can build a better, more harmonious, cleaner and more efficient one. And for the challenges that await us at CAF, we have two words: here we are. Through an introductory video, the Latin American development bank has taken a look at its main successes over the past fifty years. "At CAF we have been accompanying our region on the road to progress for 50 years. Today, more than ever, here we are and here we will continue to be firm in our commitment: to be the development bank of Latin America", they stressed.

The coronavirus pandemic has changed the world as we knew it until now, not only our health systems, but also our economies, as Luis Carranza, executive president of the CAF, has explained. In 1970, Latin America accounted for 5.5 percent of international trade and 7.3 percent of world GDP. Fifty years later, this region accounts for 5.6 percent of world trade and 7.4 percent of global GDP. Carranza has emphasized that this sense of stagnation is very different if we look at it decade by decade and analyze the situation of each of the countries. "As a region we have a productivity problem and we also have infrastructure gaps, as well as low levels of integration that we have not solved and that have led us to be the most unequal region in the world," he lamented.

However, he stressed that the strengthening of recent years has allowed the CAF to face this crisis and has made it clear that, beyond the criticism, there are examples of success in the region such as digitalization in Uruguay or Colombia's commitment to the orange economy.

Columbia University professor and Nobel Prize winner in Economics, Joseph E. Stiglitz has stressed that the success of this bank over the last few years has been an example for other organizations of the same kind. "One of the key roles of development banks is to have a long-term perspective, taking into account the disparity between social and private returns," he said after stressing that the CAF is partly a beacon of light in these turbulent times. "The CAF has a high rate of operation in its member countries; that is, it has the capacity to provide capital to be able to invest in key needs such as infrastructure and other areas at a lower cost of capital," he explained.

During his speech, Stiglitz spoke about the limitations of the market and how these influence development banks. In this sense, he regretted that the world is facing a threat such as climate change. "Efforts have been inadequate to deal with this problem, even though there was a global agreement in Paris in which the world committed itself to addressing the issue," he said before advising both public and private entities to take stronger measures to encourage, motivate and finance this type of policy.

Secondly, the role of digitisation is fundamental to understanding the impact of this crisis. "We would not have been able to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in the way we have, if we had not had these advances in research," he said. And finally, the main market constraint, according to Stiglitz, is distribution. "The COVID-19 pandemic is synonymous with inequity and inequality. This disease is unfair to those in precarious conditions. The bias present in those capital investments that try to save labor leads directly to greater unemployment, the Nobel Prize in Economics has assured; a bias that has been aggravated by the policies established during the 2008 crisis.

"Private finance is at the centre of many of these market distortions. The idea is that many of the investment needs are long term, but in between come private financial markets with short term costs. And this is precisely one of the main functions of the world banks: to have a broad perspective that takes into account the disparity between social and private returns," he said. "The challenge is not only that private markets have advanced in some areas, but they have advanced too far in others, leaving countries over-indebted. And when this happens, debt crises inevitably follow. The private sector tries to strangle countries irrationally. Not only is this inhumane, but it undermines recovery processes," he warned during his presentation, arguing that, at this time, debt restructuring "needs to be sustainable.

ECLAC Executive Secretary Alicia Bárcena fears that this crisis could turn into a lost decade in Latin America. "The coronavirus could take us back thirteen years," she said before explaining that "what we are experiencing today is the result of decades of privatization and commodification of certain public sectors such as health care".

"We have large structural gaps that we have been dragging on from even before the pandemic began," he announced, something with which Angel Gurria, secretary general of the OECD, agreed. He defended that "we are at this difficult juncture because we were already in trouble before the arrival of the pathogen. We had difficulties in terms of raw material prices, in the concentration of income, but we were also with very serious problems of competitiveness and productivity in our economies.

"It is never good that an enemy like this appears, but in the case of Latin America it came at a difficult time and showed us how unprepared we were," added Gurria before emphasizing that Latin America is in a vulnerable moment. "If there is a second wave, the numbers will be worse," he said. The OECD's secretary-general has also applauded the role of bodies like the CAF. "The role of the development bank is fundamental and therefore it must be strengthened, since it fulfils many functions, covers many spaces that the market does not manage to cover in our countries".

Alicia Bárcena has shown her concern about the idea that Latin America could emerge from this crisis with more debt or higher unemployment rates. "The international community does not fully understand the situation of middle-income countries. The CAF is a bank that serves a large number of these countries that have had to reorient their budgets; something that is not going to be enough since they are going to have liquidity problems," she insisted. During her speech, Bárcena defended the role of this bank, highlighting three of its main characteristics: that it provides resources in a counter-cyclical manner, that it serves segments of the population that are not covered by the private financial sector and, thirdly, that it can help implement medium- and long-term development strategies.

ECLAC has bet on five measures to get out of this crisis; initiatives that include implementing an emergency basic income to protect people, a temporary subsidy to small and medium enterprises, developing a welfare system and preventing economic impacts from deepening inequalities and promoting sustainability and economic integration. "We have to bet on the infrastructure of life," his secretary defended.

Former Ibero-American Secretary General and IDB President Enrique Iglesias believes that "the current crisis has transformed the foundations of the financial world. Poverty and the fall in GDP are going to mark this crisis. The financial problem has a special dimension in these countries, since our countries do not have a financial reserve". "First of all, the world is facing a breakdown of the so-called multilateral relationship. We are in a regression that will hopefully stop. In this environment, the issue of integration and regional cooperation acquires a new dimension, as or more important than in the past," he lamented during his speech.

Like the Nobel Prize winner in economics, Enrique Iglesias has opted for technology. "There is an important challenge for the regional banks to see how new technologies can be used to boost the productivity of these sectors of society," he said. And, finally, he stressed the importance of betting on the heritage that nature has given us. "The issue of climate change must be incorporated into all aspects of the development bank's policies, because it is an essential issue for continuing to live on this planet," he concluded.

Uruguay is the Latin American country with the greatest capacity to fight corruption and Venezuela the least, according to an annual index that, in the words of its authors, shows that the region has lowered its guard against this problem during the coronavirus pandemic. Humanitarian organizations have assured that the absence of real data does not allow them to maintain their effectiveness in helping the population.

"To tackle the problem of corruption, institutions must be strengthened," advised ECLAC Executive Secretary Alicia Bárcena. "One of the problems is that corruption and the culture of privilege have made inequalities natural," she lamented. "What worries me is that the state has taken a leading role. We don't want an authoritarian state, we want a social and democratic state and we want curfews to be temporary and not permanent. We must promote a social and political pact. We have to move towards a system of governance, transparency and accountability of governments," she concluded.