Europe and Japan pioneer the removal of orbit-positioned debris

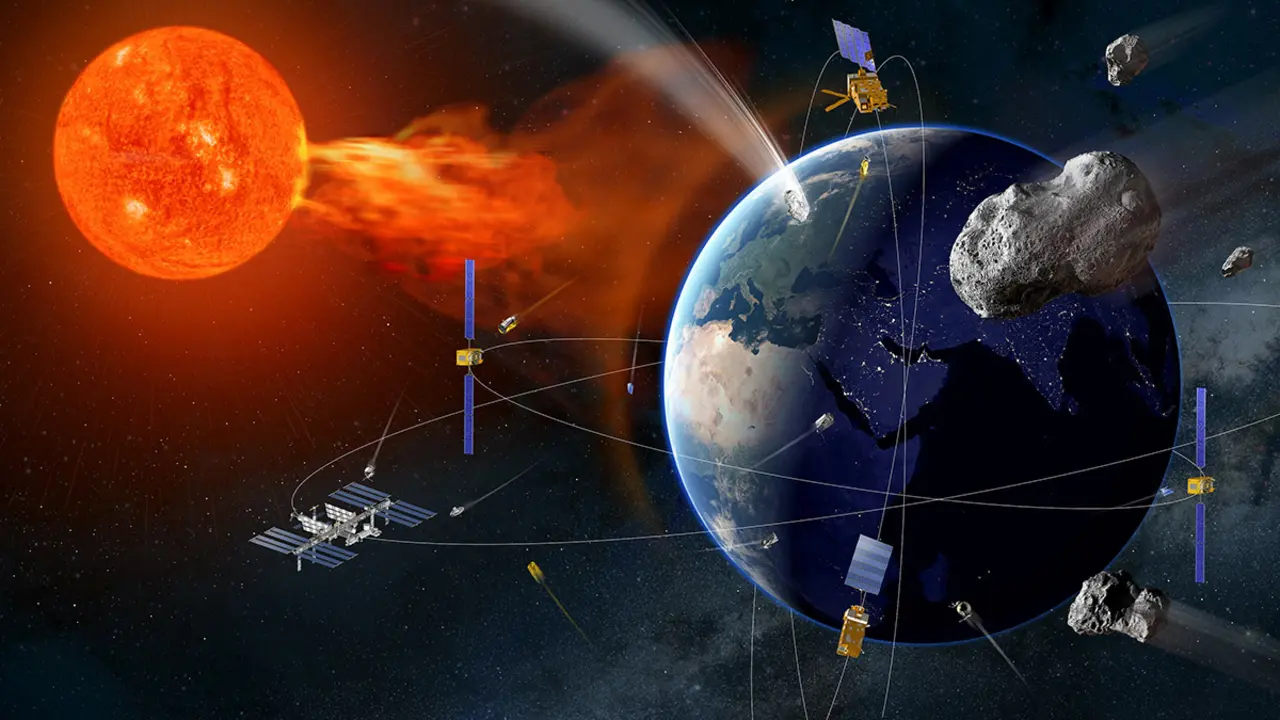

Removing, controlling or neutralising in outer space the vast amounts of fragments and debris caused by space launches that have been occurring at an accelerating rate since 1957 is an absolute necessity if the sustainability of life and the global economy are to be safeguarded.

The European Space Agency's (ESA) latest report on space debris dated June 2023 states that its radars and telescopes track 35,150 pieces of debris travelling unchecked around the planet Earth at around 28,000 kilometres per hour. But estimates from ESA's space surveillance network indicate that there are 36,500 objects larger than 10 centimetres, one million between 1 and 10 centimetres and 130 million smaller than 1 centimetre.

The scientific and engineering communities associated with space agencies around the world have for years been alerting launch service companies, satellite operators and governments to the need for standards to prevent the proliferation of debris and the urgency of removing the fragments and debris of rockets and satellites already in our outer space.

As a matter of priority, it is imperative to sweep up the Blue Planet's saturated low orbit, which is the one up to 2,000 kilometres in altitude. We have to get down to work, because "to have sustainable development on Earth, we have to ensure the sustainable use of space," is the cry of Japanese entrepreneur Mitsunobu Okada, 51, who, with his company Astroscale, founded in 2013, is committed to eliminating critical and useless objects in orbit.

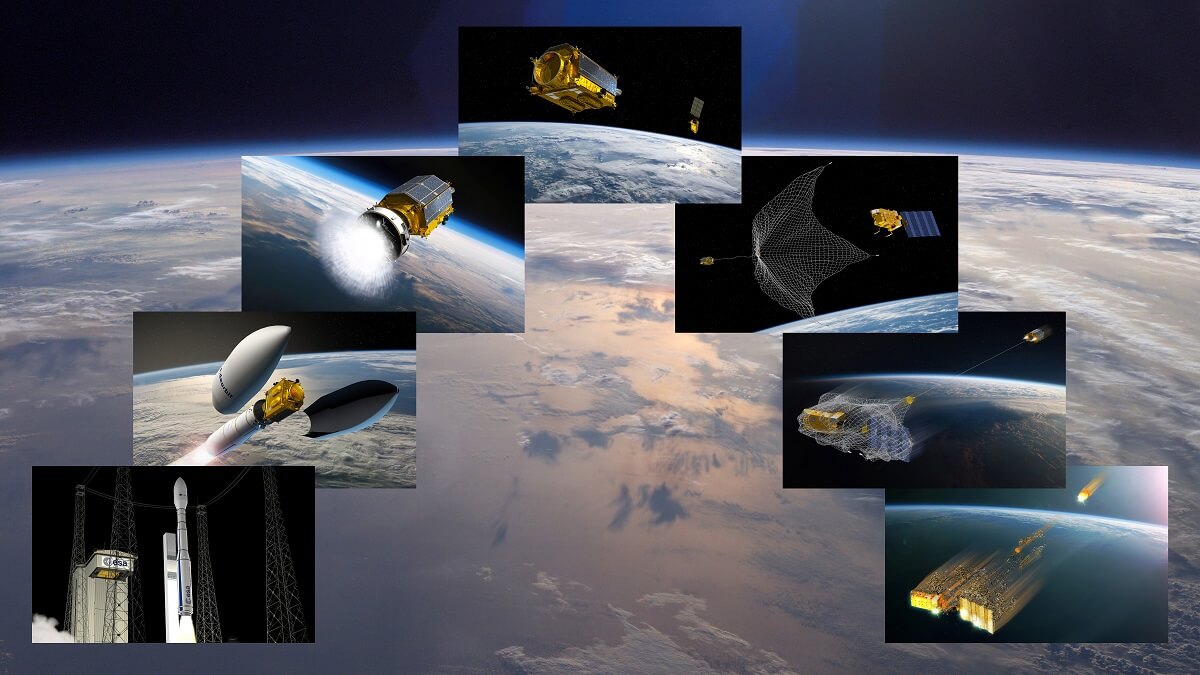

But achieving the desired goal is easy to say and very difficult to achieve. Getting rid of the debris that is already out there is a Herculean task that requires huge investments to develop the technologies that should provide the optimal solutions. Leading the way are ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the organisations most involved in tackling the challenge.

Catch, de-orbit and burn

Both agencies have started with the simplest, at least on the surface. Both JAXA and ESA have projects underway to remove the large unusable structures that, for various reasons, have been left hanging around the planet. The lead mission is Japan's ADRAS-J, which stands for Active Debris Removal by Astroscale Japan.

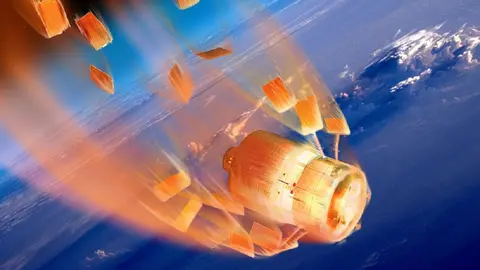

The mission aims to de-orbit and destroy without debris the second propulsion stage of the Japanese H-IIA launcher, a 3-tonne, 11-metre-long, 4-metre-diameter structure wandering uncontrolled some 600 kilometres around the Earth.

It has been in such a state of complete disarray since 23 January 2009, when it placed the Ibuki 1 space probe, manufactured by Mitsubishi Electric and dedicated to measuring the amount of carbon dioxide and methane that accumulates on our planet, into orbit. After completing its mission, the final stage of the H-IIA was trapped in orbit and did not re-enter the Earth's gravitational field, which would have destroyed it completely in its friction with the upper layers of the atmosphere.

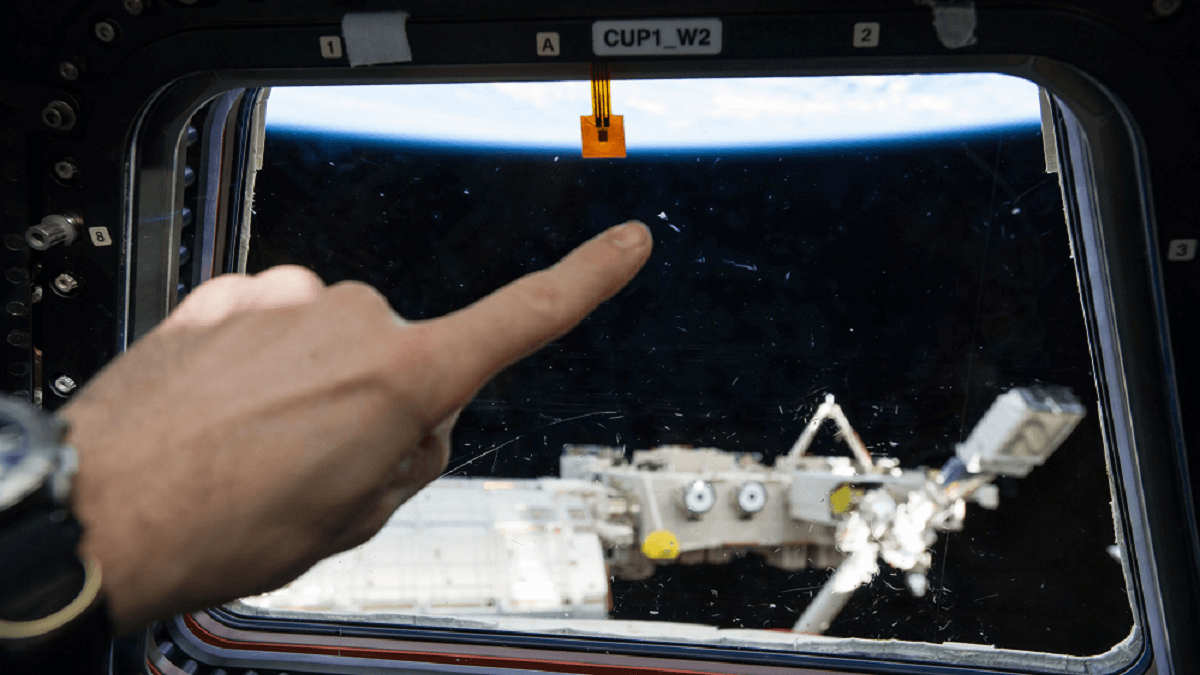

JAXA has tackled the challenge of removing what remains in space from the H-IIA launcher in two stages. In the first stage, the small 150-kilogram ADRAS-J satellite was positioned several hundred metres away from the rocket and inspected it from all possible angles. The task is not easy because "debris in low orbit moves at about 8 kilometres per second, about ten times faster than a bullet," he recalls.

It has been doing so since mid-April, after gradually approaching it since it was placed in orbit on 18 February. With the ADRAS-J task successfully completed, JAXA has now reassigned Astroscale the second and final mission: to de-orbit the huge H-IIA structure, which should happen in 2025 with a second satellite, the ADRAS-J2. Equipped with a robotic arm, it will catch and propel what is left of the rocket into the upper atmosphere and its high-speed friction will cause it to burn up completely.

The European clean-up task is scheduled for 2026

ESA is also committed to testing technologies for removing debris from space. Its initiative is called ClearSpace-1 and its goal is to capture and de-orbit the small 94-kilogram European satellite Proba 1, located at an altitude of about 550 kilometres. The task is no easy one, as "debris in low orbit moves at about 8 kilometres per second, about ten times faster than a bullet," says ESA director general Josef Aschbacher.

Manufactured by a consortium led by the German company OHB, the demonstration mission is scheduled to take off in 2026, at a date yet to be announced. ClearSpace-1 is the second attempt by ESA, which tried to develop the 1,600-kilogram e.Deorbit satellite in the past decade but cancelled it.

To date, as far as is known, the US has conducted only one test to de-orbit space debris. The Air Force Research Laboratory launched the experimental XSS-10 micro-satellite on 29 January 2003.

Weighing 31 kilos and equipped with tiny high-resolution cameras, its task was to inspect the second propulsion stage of a Boeing Delta II rocket, which was out of control in an orbit at an altitude of 800 kilometres. As far as is known, no other such mission has ever been carried out by NASA or the US Space Force.

The rate of launches into space is growing rapidly. In 2023, 222 orbital launches were carried out, 98 of which were by Elon Musk's SpaceX to position its Starlink satellite constellation, which has 2.7 million customers in 75 countries, according to the company. As of 3 May 2024, 6,327 Starlink spacecraft remain in orbit, although Musk wants to deploy a total of close to 12,000. Finding solutions to space debris and the saturation of objects in orbit requires an international cooperative effort.