Algeria 2023, the year of many setbacks

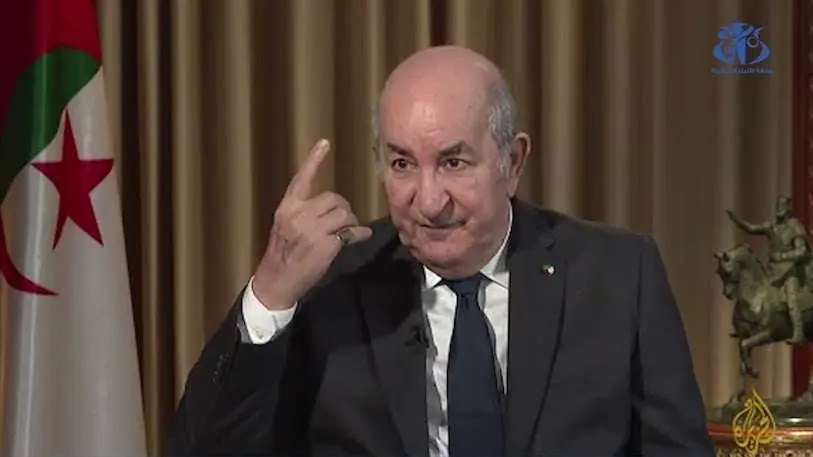

With a year to go before the end of his term of office, Abdelmadjid Tebboune may claim that "all's well in the best of all possible worlds", but deep down he's convinced that he's had a year to remember.

Although 2023 has seen its first outings in the field, the fact remains that the past year has been worse than those that preceded it.

Timid outings to Djelfa and Tindouf did nothing to enhance the credibility of a head of state who is increasingly contested by Algerians, who see him as the henchman of a most repressive military power.

A power that kidnaps citizens, including the four children of the army's late Chief of Staff, General Ahmed Gaïd Salah, Abdelmadjid Tebboune's mentor. A power that imprisons (over 400 political detainees) and sentences some 40 people to death.

A government that is transforming the country into a gigantic prison, banning thousands of citizens from all walks of life from leaving the country.

A government that mismanages the country's affairs and is incapable of providing the bare minimum for a population beset by all kinds of shortages. But it's also a power that feeds its population badly.

In a country considered one of the richest in Africa, not to say the richest, one can only take offence at the long queues that form every day, from dawn onwards, to buy a liter of milk.

The shortages have affected all the basic necessities.

Semolina, cooking oil, lentils and beans regularly disappear from shop shelves. Instead of supplying the market with sufficient quantities, the authorities, through the voice of their top official, the President of the Republic himself, explain these shortages by speculation. It went so far as to sentence a cross-border Tunisian family to 10 years' imprisonment for buying 5 liters of oil.

The same applies to a hairdresser who was in possession of the same quantity of oil. Two examples which perfectly reflect the inability of the public authorities to ensure the bare minimum of subsistence by importing sufficient quantities of the foodstuffs that Algerian agriculture is unable to produce.

When a country boasts a reserve of $70 billion, as President Tebboune did in his speech to the nation on December 25, and is unable to provide basic foodstuffs (milk, oil and semolina), it means that there are huge management shortcomings.

In fact, it's these same shortcomings that explain the impossibility of opening the religious complex of the Grand Mosque of Algiers, which cost the public treasury $1.5 billion.

Completed in April 2019, this gigantic complex includes, in addition to the prayer hall, an institute of Islamic studies, a library with a capacity of 1 million books and capable of accommodating 1,000 readers at the same time, a 14-storey museum, a hotel and shops. It remains closed despite the appointment of a rector with ministerial rank.

A rector who receives a very high salary, but who doesn't justify it because he doesn't work. He's not even pretending to set up an administration to manage this magnificent achievement.

Algerians, for their part, don't really care about the opening of the Grand Mosque of Algiers. Their first concern is water. Yes, water is in short supply in every city in the country. In Oran, the capital of western Algeria, this precious commodity is distributed sparingly.

The most fortunate may see water flowing from their taps twice a week for a few hours of the day or night. The people of Constantine are no better off.

Nor are the people of Algiers. Algerians as a whole are content to listen to Tebboune's optimistic speeches, which promise that water will flow into their taps as soon as the seawater desalination plants are completed. They continue to wait.

To distract public opinion from its real concerns, the Algerian government is trying to convince the population through "exploits" on the international scene.

One of these feats, which has long kept Algerians on their toes, is admission to the BRICS, the economic organization that brings together Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Relying on his historic friendship with Russia, China and South Africa, President Tebboune, who had visited the first two countries and named a new soccer stadium in Algiers after Nelson Mandela, the South African hero, simply thought that these gestures were enough to earn Algeria a place among the nations with emerging economies destined to rival the world's greats.

How disappointed Algeria was to see "poor little" Ethiopia accepted into the BRICS. But not Algeria. It was a disappointment that angered Algiers, which quarreled with Moscow by boycotting the Arab-Russian meeting of foreign ministers held in Marrakech on December 20.

Sergueï Lavrov was quick to pay back the "new Algeria" of the Tebboune-Chengriha duo by preferring to stop over in Tunis rather than Algiers on his way out of Morocco.

A real offense to a country which, not so long ago, enjoyed privileged relations with Moscow, while Tunisia and Morocco were considered friends of the Americans.

The quarrel between Algerian leaders is not limited to the Russians, who "have done nothing to help Algeria join the BRICS", but extends to the United Arab Emirates, "guilty of maintaining the best relations with the Moroccan enemy".

The same applies to the Spanish. Although the Algerians have finally appointed an ambassador in Madrid, they continue to take a dim view of the deepening of Spanish-Moroccan cooperation.

The year 2023 was also marked by the recall of the Algerian ambassador in Paris over the murky story of a dual national who had fled Algeria for France via Tunisia on a French passport.

Things returned to normal a few months later, as Tebboune was due to make a state visit to France on May 2.

This visit was cancelled at the last minute by who knows who (the system is so opaque), and to date Algiers has not revealed the reasons for the cancellation of this trip, which was close to the heart of the Algerian head of state.

A head of state who had rotten eggs thrown at his car in Lisbon during his visit to Portugal.

These are just a few of the setbacks experienced by the Algerian government, both at home and abroad, in a year that will soon be consigned to oblivion.