Jihadist scenarios in the southern Sahel

This document is a copy of the original published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

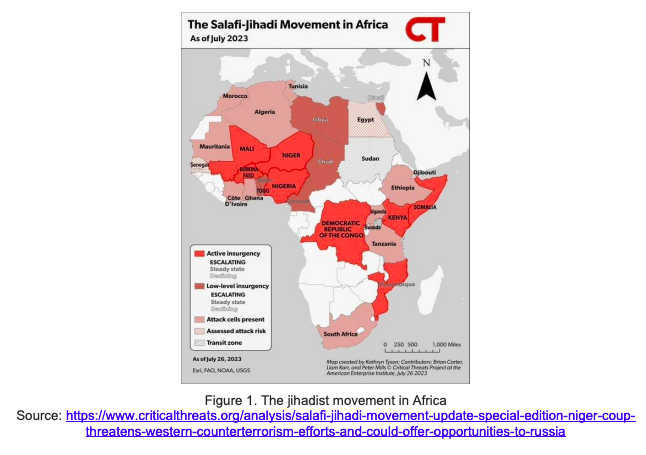

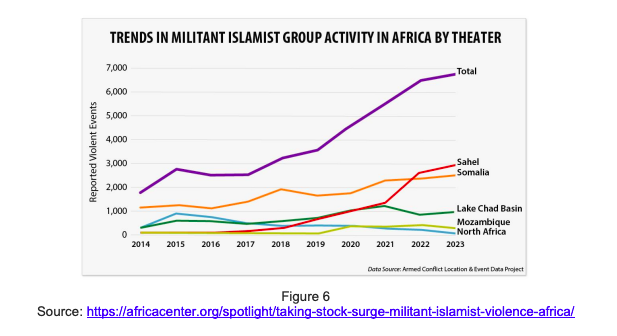

In recent years, sub-Saharan Africa has become fertile ground for the drift of global jihad. The two main global jihadist networks - Al Qaeda and Islamic State - have spread their attacks on the African continent with the aim of imposing Salafist rigorism. This paper analyses jihadist activity south of the Sahel, starting with two scenarios bordering and closely related to the Sahel region: Nigeria and the Chad Basin, and the coastal countries of the Gulf of Guinea: Benin, Togo, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana. This is followed by an analysis of the current situation in other scenarios such as Mozambique, Somalia, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda.

Introduction

In recent years, sub-Saharan Africa has become fertile ground for the drift of global jihad. The two main global jihadist networks - Al Qaeda and Islamic State - have spread their attacks on the African continent with the aim of imposing Salafist rigorism. To this effect, it is legitimate to consider that the main centre of jihadist action has shifted from the Middle East to the African continent.

While the seeds of jihad in Africa were sown in Algeria in the 1990s, military pressure from its security forces caused jihadists to flee to northern Mali, where they founded Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in 2007. Years later, the Arab Spring in North Africa and the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime in Libya facilitated the spread and strengthening of jihadism south of the Sahel, generating scenarios of political instability and terrorist violence in regions of sub-Saharan Africa1. In these scenarios, jihadist groups are able to recruit, train, supply, deploy their forces and, most importantly, generate economic income through looting, extortion, control of mining operations and control of trade routes. This operational and financial resilience means that it is unlikely that these groups will be broken up or expelled in the short term2.

A direct consequence of the levels of violence inflicted by jihadist militants is the forced displacement of some 12.5 million people from the affected regions. This is in addition to some 40 million who are suffering the consequences of violence and face food insecurity. Parts of Somalia and Nigeria are experiencing famine-like conditions3.

Some of the main causes underpinning and encouraging the advance of jihadism in the region are the violence and political exclusion practised by some governments against large sectors of their citizens. This has become the pretext for many extremists who, often out of pragmatism, embrace jihadist terrorism as a tactic against political regimes unable to meet the demands of their societies4. Directly related to this, militant groups thrive easily in regions with weak governments that are unable to provide effective state force to curb terrorists. In this regard, effective counterinsurgency requires government legitimacy, political will, control of corruption and investment in development activities for the entire population5. Another of the main drivers of jihadist terrorism in sub-Saharan Africa is its relationship with organised crime, which in addition to enabling the financing of these groups, further weakens the state, adding to the aforementioned factor.

While the aims of organised crime groups and terrorists are different - the former generally seek financial gain and the latter are ideologically and politically motivated - the means to achieve them are similar: extortion, robbery, looting, illicit trafficking and assassination. This being the case, it is often difficult to discern the authorship of criminal acts in the absence of some kind of claim. Cooperation between bandits and terrorists is one of the most problematic aspects of destabilised areas, as it creates a counter-power that is difficult for state security forces to overcome. While it is difficult to specify the relationship between the two groups, what is certain is that jihadists take advantage of the instability and weakening of state power generated by armed criminal groups6.

In recent years, the jihadist ideological landscape has fractured between the competing models of jihad and governance of Al Qaeda and the Islamic State. Al-Qaida tends to favour a relatively gradual approach, seeking to overthrow existing regimes with the aim of establishing a supranational religious state. The Islamic State, by contrast, emphasises the creation of a state out of existing countries that can challenge the current order. These differing visions were evident in the last decade with the Islamic State’s creation and subsequent collapse of a self-proclaimed caliphate, which for its supporters demonstrated that the group's more aggressive approach was feasible, but for its critics confirmed Al- Qaida's gradualist approach as more effective7.

Many violent extremist organisations with a powerful jihadist terrorist component can be found in Africa, largely linked to Al Qaeda or the Islamic State. These two large franchises, with local groups pledging allegiance to them, mostly compete with each other and rarely cooperate. When not forced to confront each other directly, they can coexist, but pursuing independent agendas. When competing for resources, territory and followers, they may engage in violent conflict that becomes the primary objective of both groups, with operations against governments and other targets taking a back seat to8.

The growth of the Islamic State on the African continent has been rapid and remarkable. In just five years it has managed to set up franchises in regions where support for jihadist ideology was previously still in its infancy. In some cases, this has been achieved by establishing alliances and synergies with local radical Islamist movements, as has been the case in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique. In others, it has taken advantage of the ideological roots generated by groups linked to Al Qaeda and has managed to provoke splits in the rival brand and the formation of new organisations that now fall under its umbrella of influence9.

This paper analyses jihadist activity south of the Sahel, starting with two scenarios bordering and closely related to the Sahel region: Nigeria and the Chad Basin, and the coastal countries of the Gulf of Guinea, namely Benin, Togo, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana. This is followed by an analysis of the current situation in other scenarios such as Mozambique, Somalia, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda.

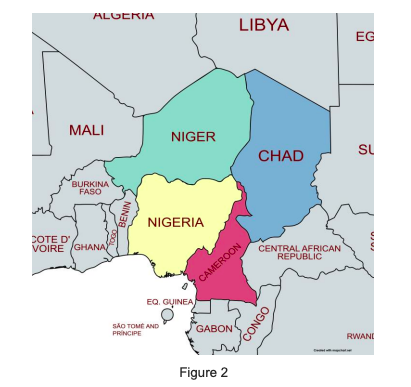

Nigeria and the Chad Basin

The main jihadist group in this region is Boko Haram. Of Nigerian origin, its terrorist activity has crossed borders and spread to neighbouring Cameroon, Chad and Niger. It started as a Sunni Islamic fundamentalist group advocating a strict form of Sharia law and has evolved into a Salafist jihadist group. In certain moments of its history, it has even maintained ties with the Islamic State. Boko Haram was the most lethal terrorist group in 2014, at the peak of its influence10. Its activity has declined considerably since then, but the group is still active.

The official name of Boko Haram is Jama'at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihad ('People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad'), but it is better known as Boko Haram, which can be translated as 'Western education is sin'. The group's origins date back to 2002 when its leadership rested with the preacher Mohammed Yusuf. In its early years, violent activity was rare. From 2008 onwards, however, a shift occurred in Yusuf's discourse from an invitation to inner conversion to Islam to a call for jihad and violence as a method of action. In 2009, an incident took place between young supporters of the group and police officers, which led to a shooting. This prompted the Boko Haram leader to publicly declare jihad, the ensuing outbreak of violence spreading across the north of the country. The response by the police and the Nigerian army resulted in a thousand of the group's supporters being killed and the extrajudicial execution of Yusuf himself. The intention of the state powers was to impose a visible and exemplary punishment that would discourage the group's followers from continuing along the path of violence, but the result was the opposite, the persecution serving to encourage his followers, now led by Yusuf's most radical deputy Abubakar Shekau, who turned Boko Haram into a machine for inflicting violence: a full-fledged terrorist group whose activity is directed against government targets and mainly Christian groups11.

The current violence is due to both Boko Haram attacks and counter-insurgency operations carried out by the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF). The MNJTF was born out of an effort by the states of the Lake Chad Basin - Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria - to pool resources against the jihadists who threaten them, and to combat them through counter-terrorism operations12.

The regional crisis provoked by Boko Haram has caused internal and cross-border displacement, physical destruction and aggravated food insecurity in the region. After more than a decade of conflict, the group continues to carry out terrorist attacks against the army and civilians, mainly in the north-eastern states: Borno, Yobe and Adamawa. Boko Haram violence in this part of Nigeria has already affected more than 13 million people, causing massive displacement and at the same time restricting movement, disrupted food supplies, hindering access to basic services and limiting agricultural activities13.

Some analysts believe that Boko Haram's violence is rooted in ethnic and religious divisions between the oil-rich Christian south and the Islamic north, and more specifically, in the interaction of different factors in northern Nigeria, such as economic grievance, extreme religious ideology and political opportunity. These elements have all shaped the context in which the insurgency has developed. Throughout 2014 and 2015, violence perpetrated by Boko Haram increased exponentially compared to previous years. Northeast Nigeria witnessed a new pattern of suicide attacks perpetrated by women, frequent kidnappings, the takeover of towns and villages, and the expansion of Boko Haram's activities beyond Nigeria's borders to include a more aggressive presence in Cameroon from the second half of 2014, and attacks in Niger and Chad since February 2015. Attacks on Christians living in the north also increased. In April 2014, the group abducted 276 Christian girls attending a school in Chibok, Borno State, an action that quickly gained global attention14.

Thanks to its notoriety and the ineffectiveness of the army and the government in curbing the group's growth and territorial dominance, in addition to the increasing number of victories won in battle, on 23 August 2014 Shekau declared that the areas of Nigeria under Boko Haram control constituted an Islamic caliphate. This came just a couple of months after Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared an Islamic caliphate in Syria and Iraq. From then on, Boko Haram was courted by the major jihadist groups, which saw the Nigerian terrorists as a formidable possibility to get a foothold in Africa, an attractive scenario for action thanks to its young population, Islamic tradition, weak governments and large uncontrolled expanses. At the time Al-Qaida already had affinity groups and franchises on the African continent, while the Islamic State presence in Africa was little more than token. When Shekau decided to swear an oath of allegiance to al-Baghdadi in March 2015, the Islamic State welcomed him with open arms. However, ideological and tactical differences of opinion between Shekau and the Islamic State leadership emerged early on and the group split into two distinct factions: Boko Haram, led by Shekau, and the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), under the control of the Islamic State. Boko Haram would continue to spread terror among the civilian population with frequent looting of villages and the abduction of women and children, whom they train to fight alongside them. About 70 % of the victims of Boko Haram attacks have been civilians, while ISWAP attacks focus on military targets and security forces. Although they do target civilians who cooperate with the authorities, they usually try to avoid harming the population, among whom they seek support15. The differentiation between Boko Haram and ISWAP was not, however, the first fracture in the jihadist phenomenon in Nigeria. Previously, in 2012, there had been a split in Shekau's ranks. The group that emerged then called itself the Vanguard for the Aid and Protection of Muslims in Black Africa, and is commonly known as Ansaru16.

In May 2021, Boko Haram leader Shekau was reported to have been killed in an operation launched by rival ISWAP to take his life. The death of the Boko Haram leader seems to have dampened the group's capacity for action, its activity having since plummeted. In quantitative terms, in 2020 Nigeria was the country most affected by jihadist violence in the region, while in 2021 Burkina Faso and Mali were ahead of it in the ranking17. The last three years have therefore been a turning point. Although it is still the most affected country in the Chad Basin, the drop in the number of registered attacks is remarkable if we compare the 242 in 2020 with the 146 in 202218.

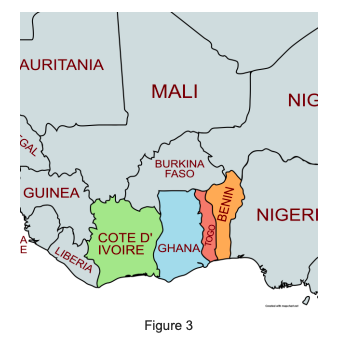

Gulf of Guinea coastal states: Benin, Togo, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana

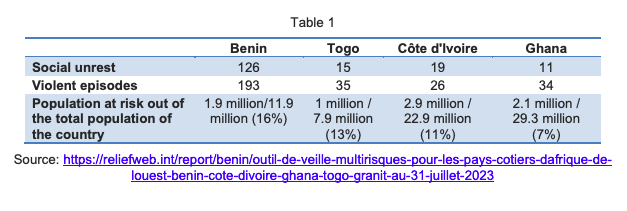

The security crisis in the central Sahel is spreading to the northern regions of the Gulf of Guinea coastal countries: Benin, Togo, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana. To this effect, violent incidents and terrorist attacks are spilling over Burkina Faso's porous borders with the coastal states. Between January 2021 and July 2023, 459 incidents - 171 social unrest and 288 episodes of violence - were recorded in the northern regions of Benin, Togo, Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire19.

The region's network of protected forest areas facilitates jihadist expansion. Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin are home to a total of approximately 588 forest reserves covering some 142,000 square kilometres, 188 of them, including four of the five largest, within 10km of an international border. In Côte d'Ivoire alone there are 249 reserves, more than a quarter of which are adjacent to others and none of which are separated by more than 26km. These protected areas are critical to preserving the region's remaining wildlife, but they are at the centre of an unprecedented security problem. As hideouts and avenues to operate unnoticed, the reserves serve as a resource that favours the expansion plans of terrorist groups20.

Jihadists linked to both the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Al Qaeda's regional franchise, Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), have been moving with impunity in the aforementioned forest reserves for years. Their movement was first observed along the transhumance corridors stretching from southern Algeria to these forests on the borders of the littoral states shortly after France's counter-terrorism operations began in Mali in 2013. Local jihadists, familiar with the aforementioned corridors, moved southwards in search of safe resting places in the forests during the French operations in the Sahel. These forest reserves hinder aerial surveillance, provide access to food and fuel supplies and facilitate the discreet recruitment of young people to join the jihadist cause among marginalised communities21. In this regard, groups such as JNIM and ISGS have proven effective in transforming a range of armed actors - bandits, rebels, militiamen, smugglers, local militants and poachers - into allied and auxiliary groups, establishing a unity of purpose to subvert state control and facilitate illicit activities22.

These four countries' access to the sea and their strategic position favour the establishment of organised crime, which uses their ports and coasts as a logistical and distribution centre. To this end, the Gulf of Guinea and in particular Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria are an entry and transit point on the cocaine and other drug and arms trafficking routes. Other important criminal activities include smuggling of tobacco, motorbikes and motor vehicles. This illicit trade directly encourages terrorist activity, because aside from the link between terrorist groups and criminal networks for the acquisition of arms, a link can be established between the illegal flow of certain products and the modus operandi of jihadist organisations. One example is the illicit trafficking of fertilisers, which are used to create improvised explosive devices, smuggled as contraband from Ghana to Burkina Faso23. This means that in the north of the coastal countries there has been a growing presence of jihadist cells, which prior to committing attacks, develop a process of rapprochement and local implantation.

The influx of violence of this kind is a source of particular concern not only for the governments of the countries bordering the Gulf of Guinea, but also for the international community, which fears that the destabilisation of the region could lead to new humanitarian crises and aggravate pre-existing problems. Benin, Togo, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana are economically stronger than their northern Sahelian neighbours, but they also have weaknesses: factors such as the lack of economic and educational opportunities among the youth, ethnic disputes, the difference in living conditions between the northern and southern populations and conflicts over land ownership facilitate the possible establishment of terrorist groups24.

Until recently, counterterrorism experts were wary of jihadists' ability to expand along the West African littoral because unlike their Sahelian neighbours, these states are more politically stable and have greater control over their borders. According to this logic, stronger security forces and governance structures would mean that jihadism was unwelcome. However, while coastal countries are not as fragile as those of the Sahel, as noted above, they do have structural vulnerabilities, perpetuated by a north-south divide in development and economic opportunities. Underdevelopment predominates in the north, due to its remoteness from the economically booming cities near the ports. This north-south divide is exacerbated by poor infrastructure and lack of roads. Northern populations are often deprived of resources such as access to employment and education, which are available in the more industrialised regions of the South25. In addition to these socio-economic and inter-community differences, there is a religious factor at play: unlike the Sahel, the countries of the Gulf of Guinea have a large Christian population and elites that sometimes tend to marginalise Muslims26.

The West African coastal states’ response to the increased threat has been to adopt a military approach to counterterrorism by increasing cross-border security. To this effect, in the last two years, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin have expanded troop deployments in their northern territories. At regional level, 2017 saw the establishment of the Accra Initiative, a multilateral security cooperation mechanism established by Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana and Togo, with Mali and Niger as observer members27. Five years after its creation, the Accra Initiative agreed to assemble a multinational military force to stop the spread of jihadism. This task force will consist of 10,000 troops, most of whom will be based in Tamale, Ghana, with an intelligence component in the Burkinabe capital, Ouagadougou. Despite the recent withdrawal of European forces from the Sahel, the Accra Initiative has received €135 million from the EU. The joint multinational force is estimated to require $550 million to function effectively, and member states hope that, in addition to the EU, the African Union, ECOWAS and Britain will be able to contribute funds. Nigeria has agreed to join this initiative as an observer and to provide air and logistical support28.

Beyond these two scenarios, terrorist hotspots can also be found in different parts of Africa, which will be briefly outlined below.

Mozambique

The protagonist of jihadist terrorism in Mozambique is the Islamic State of Mozambique, known locally as Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama'a (ASWJ). The group emerged in the Cabo Delgado region in 2007 as a splinter group of young Salafist preachers and students dissatisfied with the authorities of the Islamic Council of Mozambique, a government- recognised religious institution. At least in its early days it was not an armed group, but a marginalised heterodox Muslim community. It was gradually consolidated, succeeding in gaining followers from the most disadvantaged social strata of Cabo Delgado. Their objective eventually became the implementation of Sharia law in the areas under their control, the Islamic State of Mozambique discourse catching on among the poor fishermen of the Kimwani ethnic group. Another factor that favoured the group's consolidation was the historical grievance against the Makonde, a Christian ethnic group living in the interior that has always been linked to power. Heavy repression and increasing clashes with the Mozambican security services eventually led to the militarisation of the organisation. On 5 October 2017, ASWJ launched its first offensive against police stations in the coastal town of Mocímboa da Praia. A cycle of violence thereby began that has not stopped escalating ever since; the group is currently estimated to number between 600 and 1,200 troops. In April 2018, ASWJ pledged allegiance to the to the Islamic State has brought them benefits such as equipment, help with recruitment and training, and inclusion in propaganda campaigns29.

However, there is no clear evidence that ASWJ receives command and control orders from the Islamic State or significant external funding. The current spiritual leader of the group is Abu Yasir Hassan, a Tanzanian national, and the head of operations is Bonomade Machude, a Mozambican national. Foreign terrorist fighters originate primarily from Tanzania and Kenya, and to a lesser extent from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia and Uganda30.

Thanks to the actions of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) security forces and the Rwandan army, since July 2021 the group's terrorist activity has decreased. The 301 events and 596 fatalities suffered in 2023 are the lowest records in Mozambique since ASWJ began its terrorist activity31.

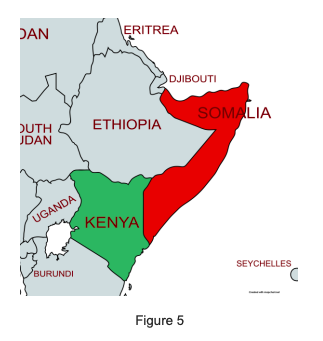

Somalia and Kenya

The jihadist group Karakat Shabab al-Mujahidin (Mujahideen Youth Movement), known internationally as Al Shabab, was formed in 2006 as the armed militia of the more extremist wing of the Union of Islamic Courts of Somalia, a movement that fought against the warlords and managed to rule in some regions of the country, but failed in its attempt to impose an Islamist regime on the whole of the fragmented Somali state. Since its formation, Al Shabab has carried out attacks in Somalia and Kenya, mainly targeting government authorities, security forces and international military operations, in particular African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) troops. Al Shabab has always supported the tenets of Al Qaeda, but only formally allied itself with the organisation in 2012. Although its ability to commit attacks declined after 2015, over the last five years it has managed to reignite its terrorist activity, regaining some of its cohesion and strength. Today, Al Shabab continues to carry out attacks mainly in the Somali capital and retains significant power in rural areas of central and southern Somalia, where it has become a provider of social services and protection for a population living under the rigorous imposition of Islamic law but nonetheless experiencing a sense of belonging, especially among young people with no other life expectancy32.

Since August 2022, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has been leading a major military offensive against Al Shabab. Air strikes and military operations have meant significant losses for the jihadists, although UN reports33 consider that its financial and operational capacity has not diminished, and the group is estimated to have between 7,000 and 12,000 fighters. Al Shabab is reportedly generating $100 million a year from the taxes it collects on Somali soil. In the past six months, the group has focused on carrying out strategic attacks against Somali military bases and those of the African Union Mission in Somalia. In their most deadly attack, more than 500 fighters stormed a base of the mission in Buulo Mareer, killing a significant number of Ugandan troops. But the Al Shabab jihadists are not the only ones operating there: since 2016 they have been sharing the stage with the Islamic State in Somalia, a group that aims to take over the leadership of the local jihad and which operates mainly in the Puntland region. However, the Islamic State in Somalia currently does not have the capacity to control large areas of land or to conduct major operations, and is estimated to have only 100-200 fighters34.

Somalia accounted for 36% of Islamist militant-related fatalities on the African continent in 2022, making it the second most active scenario after the Sahel35.

In Kenya, Al Shabab has committed significant terrorist actions in response to the Kenyan government's dispatch of troops to Somalia in 2011 to cooperate in the fight against the jihadist group. In 2013, the organisation attacked a shopping centre in Nairobi, killing 67 people36; in 2015 it attacked the campus of Garissa University, killing 147 students37, and in 2019 it attacked a hotel in Nairobi, killing 21 people38. In 2020, Al Shabab attacked a military base in Kenya used by the US military39. Jihadists have also raided schools and buses near the Somali border.

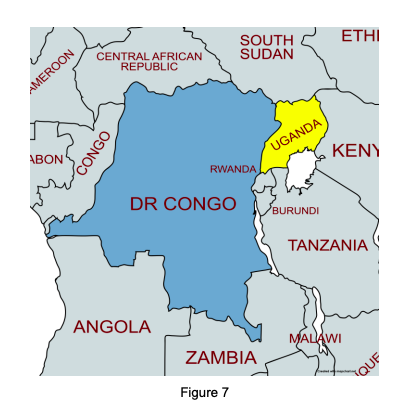

Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda

The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) is a group founded in the mid-1990s by a Ugandan Christian convert to Islam, Jamil Mukulu, who brought together supporters dissatisfied with the Ugandan government's treatment of Muslims, who make up about 14%40 of the predominantly Christian population of the country. Under pressure from Ugandan security forces, the FDA regrouped in the interior of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), in the territory of Beni. From their bases in the Congolese mountains, they promote jihadist ideology, making incursions into south-western Uganda. Over the decades they have committed numerous terrorist acts in both the DRC and Uganda against military and civilian targets41.

In 2018, the FDA joined the Islamic State and renamed itself the Islamic State in Central Africa. The Islamic State claimed its first attack in this scenario in April 2019: an attack on the DRC army near the Ugandan border. Between 2014 and 2020, the FDA/Islamic State killed approximately 4,000 civilians. In October 2020, they staged a prison raid in the Congolese town of Beni that resulted in the escape of some 1,300 prisoners, including some 250 fighters from the jihadist group. In April 2022, they carried out their first suicide bombing in Goma (DRC), and in August 2022 they carried out another prison break in North Kivu (DRC), during which 800 prisoners were released42.

In January 2023, terrorists detonated an explosive device at the Lubiriha church in Kasindi, Beni, the explosion killing 16 people and injuring more than 60 civilians. The bomb, the most powerful ever used by the FDA, caused the highest death toll ever recorded in a single explosion43.

In 2021, after the FDA had already killed hundreds of civilians, the DRC and Ugandan authorities decided to work together to fight the rebels. In November 2021, Uganda sent troops to assist the DRC in the fight against FDA members as part of Joint Operation Shujaa, which targets the group's commanders and fighters and is successfully dispersing the jihadists from their traditional strongholds. The organisation currently has an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 active fighters, led by Seka Baluku (alias Musa Baluku)44.

Conclusions

While jihadist terrorism is generally on the rise in sub-Saharan Africa, smart and effective action by the states involved could reverse the trend. In the scenarios bordering the Sahel, the political fragility of the Sahelian coup governments and regional insecurity will reinforce each other, and the jihadist threat to the Chad Basin and the Gulf of Guinea coastal states can therefore be expected to grow. However, several factors could hinder the progression of jihadist groups further south, starting with the need to build local alliances. To this effect, as jihadist groups move into southern regions, it will become more difficult for them to establish lasting bases and gain the support of the inhabitants of these predominantly Christian areas. They will also lose much of their ability to move undetected among the local population. However, the recent wave of coups in the Sahel has shown that jihadists do not need to spread across a country's territory to create a crisis that leads to state failure and chaos.

Experiences in the fight against jihadist groups in sub-Saharan Africa have demonstrated the effectiveness and important role being played by international missions and cooperation alliances of a regional nature, such as the Joint Multinational Force, which includes the armies of the States of the Lake Chad Basin; the Accra Initiative; the security forces of the Southern African Development Community in Mozambique; the African Union Mission in Somalia; and the alliance of the armies of the DRC and Uganda in Operation Shujaa. These joint operations are significantly limiting the capabilities of the jihadists, although their success in some cases goes hand in hand with an escalation in the intensity of attacks, as is happening in Somalia and the DRC. Having said that, these are short-term reactions from the terrorists which, if the successes of the operations are prolonged, cannot be sustained in the medium to long term.

As a complementary measure to military action, government success against jihadist groups will not be possible without the re-establishment of legitimate governance processes that strengthen state action and enable the provision of social services to reach all citizens, especially those belonging to groups likely to be attracted to jihadist action. The aim is for violent action to cease to be a possible route to a guaranteed livelihood or a theoretically more just social order.

Legitimising and strengthening state action capable of linking security and development could prove to be the most effective strategy to quell the jihadist threat in sub-Saharan Africa.

Óscar Garrido Guijarro*

Analyst at the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies PhD in Peace and International Security

@oscargarrido

Referencias:

1 DÍEZ ALCALDE, Jesús. "Africa 2019: the spread of the jihadist threat and the urgency of weighing up the response". Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, 23 January 2019. Available at: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2019/DIEEEA03_2019DIEZ-YihadArabe.pdf

2 SIEGLE, Joseph. "Taking Stock of the Surge in Militant Islamist Violence in Africa". Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 7 March 2023 Available at: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/taking-stock-surge-militant-islamist-violence- africa/

3 SIEGLE, Joseph and WILLIAMS, Wendy. "Militant Islamist violence in Africa surges - deaths up nearly 50%, events up 22% in a year", The Conversation. 7 March 2023. Available at: https://theconversation.com/militant-islamist- violence-in-africa-surges-deaths-up-nearly-50-events-up-22-in-a-year-200941

4 DÍEZ ALCALDE, Jesús. Op. cit.

5 SIEGLE, Joseph and WILLIAMS, Wendy. Op. cit.

6 SÁNCHEZ HERRÁEZ, Pedro. "Sahel: jihadist epicentre in West Africa", Strategy Notebook 2014 (International Terrorism: Mutation and Adaptation of a Global Phenomenon). Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, 27 December 2022. Available at: https://www.ieee.es/publicaciones-new/cuadernos-de- estrategia/2022/Cuaderno_214.html

7 THORSON, Charles. "The Future of Jihadism in a Multipolar World', Stratford. 25 August 2023. Available at: https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/future-jihadism-multipolar-world

8 UNITED NATIONS. Thirty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team pursuant to resolution 2610 (2021) concerning ISIL (Da'esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities. 25 July 2023. Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N23/189/77/PDF/N2318977.pdf?OpenElement

9 IGUALADA, Carlos. "Is a new Daesh jihadist caliphate in Africa possible?", International Observatory for Terrorism Studies. 28 July 2022. Available at: https://observatorioterrorismo.com/actividades/es-posible-un-nuevo-califato- yihadista-de-daesh-en-africa/

10 INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMICS AND PEACE. Global Terrorism Index 2014: Available at: https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Global-Terrorism-Index-Report-2014.pdf

11 FUSTER, R. “Descripción y análisis de un grupo terrorista. Boko Haram. Un ejemplo de los riesgos

(inter)nacionales en un Estado fallido”, Revista del Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, no. 18. 2021, pp. 177-

208. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/604108

12 INTERNATIONAL CRISIS GROUP. “What Role for the Multinational Joint Task Force in Fighting Boko Haram?” (Report, No. 291). Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/291-what-role-multinational-joint-task- force-fighting-boko-haram

13 ACAPS. “Nigeria. Boko Haram”. 2021. Available at: https://www.acaps.org/country/nigeria/crisis/boko-haram-

14 ADAMO, A. "The terrorist and the mercenary: Private warriors against Nigeria's Boko Haram", African Studies, vol.

79. 2020, pp. 339-359.

15 SUMMERS, M. and YAGÜE, J. "Boko Haram and ISWAP: two sides of the same coin" (OIET Paper, 14/2020). Available at: https://observatorioterrorismo.com/actividades/boko-haram-e-iswap-dos-caras-de-la-misma-moneda 16 LABORIE, M. "¿Quién es Ansaru?", Boletín del Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. 2013. Available at: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_informativos/2013/DIEEEI05-2013_Quien_es_Ansaru_MLI.pdf

17 OBSERVATORIO INTERNACIONAL DE ESTUDIOS SOBRE TERRORISMO, COVITE. Jihadist Terrorism

Yearbook 2021. Available at: https://observatorioterrorismo.com/eedyckaz/2022/03/ANUARIO-2021-version-final.pdf

18 OBSERVATORIO INTERNACIONAL DE ESTUDIOS SOBRE TERRORISMO, COVITE. Jihadist Terrorism

Yearbook 2022. Available at: https://observatorioterrorismo.com/eedyckaz/2023/07/ESPANOL-ANUARIO- 2022_final.pdf

19 GRANIT. "Outil de veille multirisques pour les pays côtiers d'Afrique de l'Ouest". 11 September 2023. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/benin/outil-de-veille-multirisques-pour-les-pays-cotiers-dafrique-de-louest-benin-cote- divoire-ghana-togo-granit-au-31-juillet-2023

20 BROTTEM, Leif. "Jihad Takes Root in Northern Benin". The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, 23 September 2022. Available at: https://acleddata.com/2022/09/23/jihad-takes-root-in-northern-benin/

21 BERNARD, Aneliese. "Jihadism is spreading to the gulf of guinea littoral states, and a new approach to countering it is needed". Modern War Institute, 9 September 2021. Available at: https://mwi.westpoint.edu/jihadism-is-spreading- to-the-gulf-of-guinea-littoral-states-and-a-new-approach-to-countering-it-is-needed/

22 NSAIBIA, Héni. "In Light of the Kafolo Attack: The Jihadi Militant Threat in the Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast". The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, 24 August 2020. Available at: https://acleddata.com/2020/08/24/in- light-of-the-kafolo-attack-the-jihadi-militant-threat-in-the-burkina-faso-and-ivory-coast-borderlands/

23 COLLADO, Carolina. "Assessment of the jihadist threat and its potential for expansion in the Gulf of Guinea", International Journal of Terrorism Studies. August 2021. Available at: https://observatorioterrorismo.com/eedyckaz/2021/08/5-Evaluacion-de-la-amenaza-yihadista-y-sus-posibilidades-de- expansio%CC%81n-en-el-Golfo-de-Guinea-Carolina-Collado.pdf

24 SUMMERS, Marta. "Jihadist Activity in the Maghreb and Western Sahel", Jihadist Terrorism Yearbook 2022. Available at: https://observatorioterrorismo.com/eedyckaz/2023/07/ESPANOL-ANUARIO-2022_final.pdf

25BERNARD, Aneliese. Op. cit.

26 GUIFFARD, Jonathan. “Gulf of Guinea: Can the Sahel Trap Be Avoided?”. Institut Montaigne, 1 February 2023. Available at: https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/gulf-guinea-can-sahel-trap-be-avoided

27 Idem.

28 AFRICA DEFENCE FORUM. "Accra Initiative Takes Aim at Extremism's Spread". 13 December 2022. Available at: https://adf-magazine.com/2022/12/accra-initiative-takes-aim-at-extremisms-spread/

29 MORA TEBAS, Juan Alberto. “Cabo Delgado Conflict (Mozambique): Risk of 'Sahelisation' in Southern Africa?”, Geopolitical Conflict Landscape 2022. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. Available at: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/panoramas/PGC2022/PGC2022_Capitulo08.pdf

30 UNITED NATIONS. Op. cit.

31 AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES. "African Militant Islamist Group-Linked Fatalities at All-Time High". 31 July 2023. Available at: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/africa-militant-islamist-group-linked-fatalities-at-all-time- high/

32 DÍEZ ALCALDE, Jesús. "Somalia: there is a future', Geopolitical landscape of conflicts 2019. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. Available at: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/panoramas/panorama_geopolitico_conflictos_2019.pdf

33 UNITED NATIONS. Op. cit.

34 Idem.

35 AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES. Op. cit.

36 HOWDEN, Daniel. "Terror in Nairobi: the full story behind al-Shabaab's mall attack", The Guardian. 4 October 2013. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/04/westgate-mall-attacks-kenya

37 BBC NEWS. "Who are the extremists of Al Shabab, the group that killed 147 students in Kenya?” 02 April 2015. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/04/150402_perfil_al_shabab

38 BBC NEWS. "Kenya attack: 21 confirmed dead in DusitD2 hotel siege". 16 January 2019. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-46888682

39 EFE. "Al Shabab attacks a military base in Kenya where US military personnel are stationed. UU.", La Vanguardia. 05 January 2020. Available at: https://www.lavanguardia.com/internacional/20200105/472718510390/al-shabab- ataca-base-militar-kenia-militares-estadounidenses.html

40 CIA. "Uganda", The World Factbook. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world- factbook/countries/uganda/#people-and-society

41 GLOBAL SECURITY. "Allied Democratic Forces”. Available at: https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/para/adf.htm

42 CIA. "Terrorist organisations", The World Factbook. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world- factbook/references/terrorist-organizations/

43 BNN NEWSROOM. "ISIS-Linked Bombing at DR Congo Church Kills 17 and Injures Many". January 2023. Available at: https://bnn.network/watch-now/isis-linked-bombing-at-dr-congo-church-kills-17-and-injures-many/ 44 UNITED NATIONS. Op. cit.