Spaç, Enver Hoxha's cultural heritage that Albania wants to forget

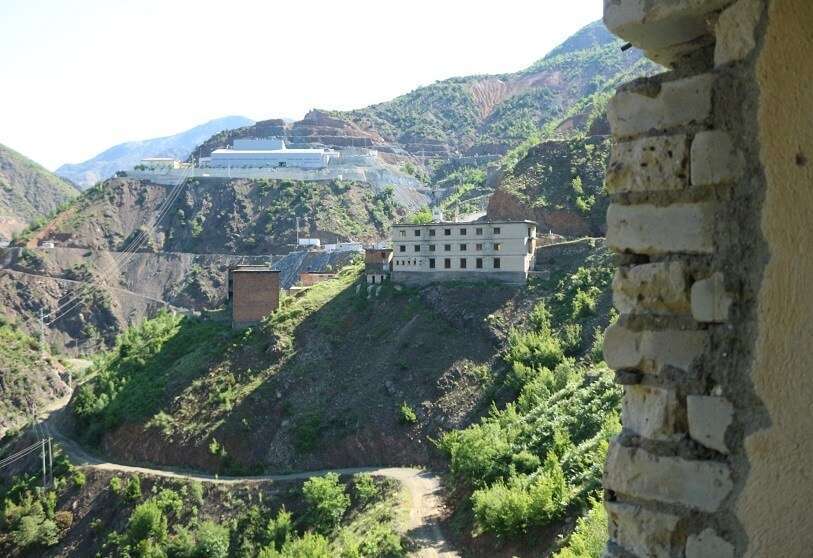

Lost among the hills surrounding the small municipality of Mirditë, in the north of Albania, only an hour away from Tirana, and connected to mines that served as forced labour camps for the prisoners. Spaç prison is the Stalinist-style gulag where Enver Hoxha sent all those who dared to confront the Albanian Stalinist regime.

Enver Hoxha ruled Albania between 1944 and 1985. Stalinist to the core, so much so that he broke ties with the rest of the European communist leaders such as Josip Broz Tito, head of state of the Second Yugoslavia, and Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's successor, believing that they were opening up to the West, following their condemnations of Stalin's crimes.

"At the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union in 1956, Albania remained a party. However, after that, they started to think about how to leave the communist group of the USSR because of this change of leadership," explains Fatos Lubonja. Fatos is one of Albania's most renowned writers and a dissident of the Hoxha regime. Founder of the magazine Përpjekja (effort in English), Lubonja spent more than 17 years in prison for 'Agitation and Propaganda' against the regime and for 'Belonging to a counter-revolutionary organisation', which was punishable by death.

After the break with the rest of the communist leaders, Hoxha pushed through a new constitution for the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, marked by adherence to Marxist precepts, anti-revisionism and national self-sufficiency, which completely isolated the country. "During this period they tried to build ties with China, [Hoxha] carried out a kind of cultural revolution, especially in the period between '67 and '68," explains Fatos, "he declared Albania the first atheist state, destroying churches or converting them into shops or sports palaces. Many priests and believers were imprisoned, accused of being agents of the Vatican," the writer recalls.

In the last decade of his life, the leader came to define himself as "the last defender of authentic Marxism-Leninism", which made the dictator fear a revolution, causing him to see ghosts everywhere. Enver Hoxha's paranoia led him to build a total of 173,000 bunkers for fear of foreign invasion. Not only that, but in the 1970s he initiated a social purge that led to the imprisonment, exile or death of thousands of people suspected of treason against the regime. This led him to build 23 prisons and 48 Stalinist-style internment camps. The worst of these, Spaç.

"It was then, when the campaign started, that I was imprisoned. There were three different purges; the first one for ideology, television and radio directors and even members of the Central Committee were imprisoned accused of being liberals (people who wanted to open the door to the degenerations of the West), among them my stepfather. This purge was followed by a repression of intellectuals, artists, painters, writers. Most of them were imprisoned or deported," recalls Lubonja. The second purge took place within the ranks of the army, accusing many of a military coup. The third was defined as sabotage, an accusation that ended with the then finance and economy ministers being executed.

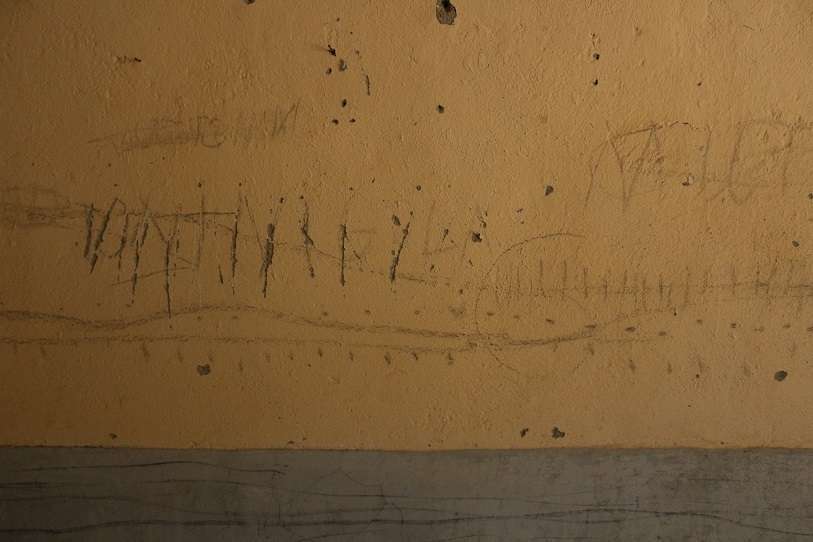

Prior to 1968, communist Albania had two types of prisons: isolation prisons and forced labour camps. Spaç combined the two. Entering this former labour camp, now in ruins, the cold invades, despite the thirty degrees outside. Abandoned rooms with their walls torn down, but those that remain standing still bear the graffiti of the former prisoners: the count of the days (or maybe months or years) they were locked up, their names, phrases and even drawings that would have had their meaning for these dissident artists and politicians condemned to live in the gulag.

The National Museum of History in Tirana estimates that the communist regime held almost 50,000 people for political reasons, in a system of 23 prisons and 48 internment camps. 5,577 men and 450 women were executed; about 1,000 died in prison; 17,900 were imprisoned for a total of 914,000 years in prison and only about 2,700 of them are still alive today, according to the Albanian Institute for the Integration of Former Political Prisoners. With a maximum prison population of around 1,400, Spaç was a small cog in a larger machine of oppression, but the inhumane conditions of the mine and the high profile of some of the camp's political prisoners, many of them intellectuals, gave it great symbolic weight. This gulag is one of thousands of examples of the repression that Hoxha's Albania displayed. It established itself as the worst communist regime in Europe.

Sentences for any kind of treason against the regime ranged from three years' imprisonment to the death penalty. However, "the common sentence recorded in the constitution was that of fleeing the country as a crime," says Fatos, "this was not considered illegal border crossing but treason. And the sentences ranged from ten years to the death penalty". This was the case for Zenel Dragu, a former prisoner in Spaç and founder of the Association of Former Political Prisoners of Shköder, "when someone was against the government they were judged as 'traitors of the people' and everyone knew the consequences of that", he recounts in an interview for Observatori i kujtesës (Observatory of Memory).

Zenel was living in Shköder, a major Albanian town in the north of the country, when he tried to flee. "I didn't want to go against the regime, I just wanted a better life. So his intention was to reach the United States, crossing into Montenegro and from there to Italy by boat. "When someone fled, the consequences were felt by the family; they were deprived of access to public services such as schools, and even fired from their jobs. This is corroborated by Lubonja: "You could meet the families or children of the former persecuted or convicted, who had not been able to study because if you were considered a close contact of someone who had been convicted, you could not continue your studies. My daughters, for example, when they grew up, could not go to university in Albania."

"Albania finds you wherever you are," that's what Zenel was told when he was caught crossing into Montenegro. "The people in that first village in Montenegro worked for the regime's Secret Service and pretended they were helping us when, in fact, they were informing on us," recounts the association's leader, which caused him to live locked up in Spaç for 14 years.

"This was the hardest work of my life," he says, explaining that he had to work holding a 36-kilogram electric hammer for hours on end. "The jobs in the mine were divided into three different shifts, with much higher demands than for those who were outside workers, and if you couldn't meet them you were punished in isolation cells. You didn't get a single day off. You got up at five in the morning, had breakfast, went to the toilet, waited for the officers who arrived at half past six in the morning to take you to the mine. In total it was about ten hours, between arriving, working and returning," explains Fatos. The writer spent his last months in Spaç in isolation cells because of his refusal to work. The reason for this is that he gave up, "I thought I was going to die in that gallery, after 17 years I couldn't survive, it was terrible; not only because of the hard work but also because of the fumes you had to breathe. The mine was an unimaginable situation".

"The most important thing to see is not only where you ate or slept, but the whole enclosure surrounded by mountains, with fences and control towers everywhere, and above all the mine. Hoxha took it upon himself to make this place, where these intellectuals accused of counter-revolution for writing a letter went, inaccessible. Mountains surround the battered buildings and the mine is barely visible. To get there, a poorly maintained dirt road separates the compound from any contact with the rest of the population. It takes more than twenty minutes by car down the mountain to reach the nearest village.

Hoxha was so afraid of Western invasion that prisoners were forced to "listen to the dictator's messages, the newspaper had to be read aloud, prisoners were recruited to spy and inform on their comrades if they spoke ill of the regime". However, conspiracies aside, the dictator's fears became real. At least in Spaç, for this gulag was the first and only place in Hoxha's Albania to witness resistance to the regime. This is what the explanatory posters in this kind of museum in ruins tell us. On 21 May 1973, for three consecutive days, the prisoners took control of the gulag.

Shouting anti-communist slogans, cheering for Western-style democracy and, for the first time in history, the voice of an Albanian part of Western Europe was raised. This resistance was repressed in the most brutal way; special military forces were sent in and the participants of this revolt were sentenced to more years in prison and even executed.

Dozens of rooms already destroyed and held together with iron bars are what remains of Spaç. The government has done nothing to maintain this prison, an Albanian cultural heritage. "Unfortunately, the way you have seen it is a consequence of the degradation of the situation, but that has to do with the years after the fall of communism, when the elites who controlled power were not interested in keeping it as it was, in making it a space for young people to visit and learn about history," laments the writer, who has raised his voice on more than one occasion to denounce the Albanian government's lack of interest in maintaining the country's cultural and historical heritage.

The mines can no longer be seen when you visit Spaç. They have been replaced by an excavation site owned by a Turkish company. You can't even read the gulag signs any more, it's the explanatory signs that guide you through the ruins. It would be impossible to distinguish what used to be an isolation cell from a punishment cell without them.

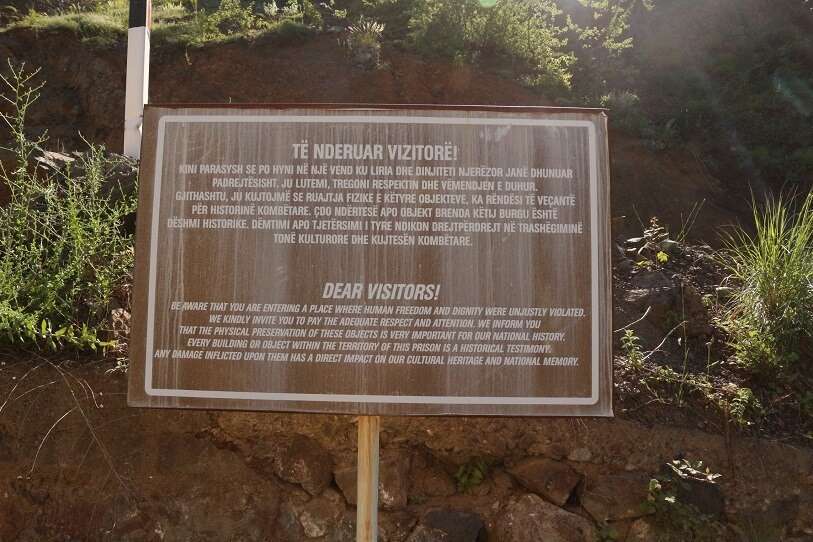

"Dear visitors, be aware that you are entering a place where freedom and dignity were unjustly violated. We invite you to be respectful and attentive. We inform you that the physical preservation of these objects is very important for our national history. Every building or object on the grounds of this prison is a historical testimony. Any damage has a direct impact on our cultural heritage and national memory," asks the sign at the entrance of the gulag-turned-museum. However, contrary to this information, the maintenance of Spaç is not due to governmental action. It is the association Cultural Heritage without Borders that has taken on this task. "When a businessman sees a forest, he only sees the number of trees he can cut down to make more money; the government sees these sites like Spaç, which are our cultural heritage, as trees to be cut down to make money out of it," laments Fatos.

The Spaç prison is one of the buildings that best describes Albania's recent past, a clear reflection of the Enver Hoxha regime, which was responsible for the country's global isolation at the end of the 20th century, the economic and political consequences of which it is still struggling to mitigate. And even if the new governments prefer to ignore this past in order to strengthen their ties with the West and finally join the EU, something that was planned for 2020, they should remember, as does Tirana's BunkArt 2, one of Hoxha's thousands of bunkers converted into museums, that "he who forgets his history is condemned to repeat it". That is why Latos, Zenel and the rest of the 2,000 former Spaç prisoners continue to call for the maintenance of the worst gulag in communist Albania.