The Tindouf mirage: the right of return as a dignified solution

- The wall of humanitarian smoke

- A regime without democratic oxygen

- Algeria: guardian, accomplice and beneficiary

- The right of return as a moral imperative

- Conclusion: breaking the illusion

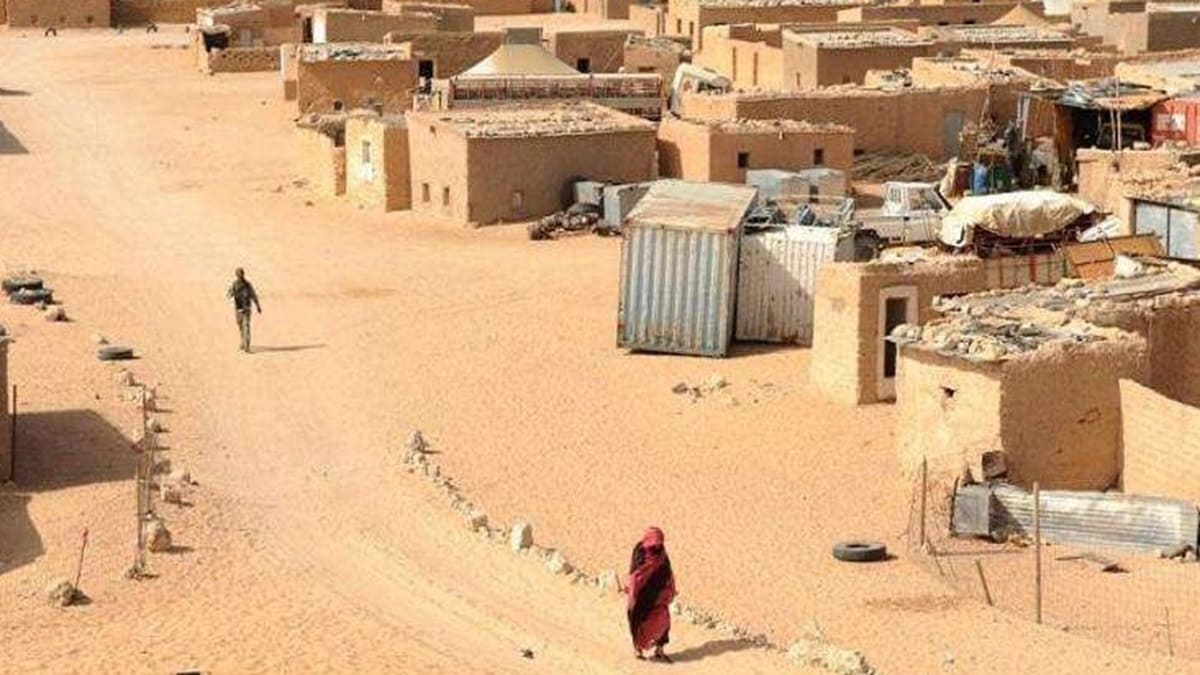

The Algerian desert harbours a paradox that has already lasted too many decades: in the name of the ‘Sahrawi cause’, tens of thousands of people are being held captive in closed camps, run by an armed group – the Polisario Front – which exercises absolute power without being accountable to anyone.

Those who proclaim themselves spokespeople or protectors of a people repress that same people, while Algeria provides them with territory, logistics and silence. This is the uncomfortable truth that today, more than ever, deserves to occupy the pages of the international press. Far from this being the case, the opposite is true, especially in Spain.

The wall of humanitarian smoke

Since 1975, the Polisario has skilfully cultivated the image of a self-proclaimed ‘liberation movement’ and pseudo-state. However, documented facts dismantle this narrative. Reports from the United Nations, human rights organisations and even European court rulings and cases still pending in countries such as Spain indicate that former Sahrawi combatants have held key positions in jihadist networks in the Sahel – AQIM, MUYAO, EIGS – and are involved in arms and human trafficking. This metamorphosis reveals a violent and pragmatic DNA: when revolutionary fervour is lacking, organised crime is used to finance the structure.

The criminal streak is not only external. Within the camps, the diversion of humanitarian aid has become a power base: the European Anti-Fraud Office estimated that 105 million euros ended up in the pockets of Polisario leaders and Algerian officials in a single decade. Food sold in Algerian towns and neighbouring countries, medicines resold in Mauritania, or money laundered in Spain through networks linked to Hezbollah, as was revealed at the time. This is how an apparatus that claims to protect refugees is financed while locking them into an eternal camp ordeal. Thus, by depriving them of their few means of subsistence, genocide is being perpetrated. One of the worst kinds: in slow motion.

A regime without democratic oxygen

What Western public opinion sees as ‘refugee camps’ is, for many Sahrawis, a kind of contemporary gulag. Polisario militias control movement, issue permits to leave the compound and decide who gets scholarships, jobs or simple rations of flour. Those who dissent disappear or end up in secret prisons such as Errachid, where ‘rectal syringing’ with salt water, electrocution and prolonged isolation are common methods.

Added to political repression is a barely mentioned ethnic apartheid: families of black descent – the Haratines – inherit menial tasks and have no representation in internal bodies. Modern slavery in the 21st century. This caste system belies any narrative of emancipation within the falsely claimed egalitarian society that the Polisario has advocated since its inception, and confirms that they are reproducing within Tindouf the oppression they claim to be fighting.

Algeria: guardian, accomplice and beneficiary

None of the above would be possible without Algiers' consent. The Algerian government provides land, weapons and diplomatic protection, but shirks its responsibilities as a host state. It prevents UNHCR, or the relevant entity, from conducting a full census – the actual number of refugees remains a mystery – and vetoes independent human rights missions. This opacity protects a lucrative status quo: for every sack of European flour diverted, someone collects an informal tax; for every shipment of subsidised fuel, a military faction fattens its coffers. The suffering of the Sahrawi people is profitable.

Faced with this labyrinth of impunity, Morocco has offered a realistic way out: a plan for advanced autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty that guarantees local self-government, massive investment in infrastructure and full inclusion in national life. The southern provinces now have the highest literacy and health coverage rates in their history; they attract tourism, renewable energy and technology start-ups. It is there, and not in the dusty huts of Tindouf, that there is genuine hope for the future for Sahrawis who long to prosper without guardianship.

The right of return as a moral imperative

International law is clear: everyone has the right to leave any country and return to their homeland. In Tindouf, that right is being denied. No miracle solutions are needed – state-of-the-art biometric censuses or humanitarian corridors guarded by blue helmets – to begin breaking the chains. A few initial steps would suffice:

Authorise the entry of international human rights organisations and independent observers to register the wishes of those who wish to return and carry out verification missions. These organisations should also establish a mechanism to monitor the distribution of humanitarian aid and prevent its diversion.

Establish a mechanism for the census or documentary identification of the population held in the camps, under international supervision by the agreed entity or entities, so that once identified, those who wish to return can be provided with valid passports.

- Agree on a system that guarantees the right of Sahrawi refugees to return voluntarily, freely and with dignity to Morocco, without conditions or reprisals.

- One example could be to allow the organisation of gradual return convoys – entire families, the elderly, the sick – accompanied by the Red Crescent and international NGOs.

- We are not talking about pipe dreams, but about basic obligations that Algeria and the Polisario systematically evade.

Europe, so rigorous when it comes to monitoring established democracies, has shown surprising leniency towards these violations. The MPs who sign resolutions on the Sahara rarely visit the camps, except for the most radical or militant ones, for whom everything the Polisario does is fine because, blinded by self-deception, they cannot conceive of anything else. And they always visit under the guidance of the Polisario Front, which shows them what it wants them to see and hides what compromises it. Similarly, the humanitarian aid organisations and public administrations that send aid do not demand on-site audits. The case of Spain is particularly egregious, where the Polisario usurps the role of victim from the people in its charge in order to raise funds and material goods from Spanish taxpayers. There, without being accountable for their final destination, is where personal gain begins. Meanwhile, the rhetoric of self-determination serves as an alibi to perpetuate a humanitarian industry that keeps tens of thousands of people in controlled poverty.

Conclusion: breaking the illusion

Sahrawi refugees do not need more revolutionary slogans. They need the key that will open the door to a home where the word ‘future’ is not synonymous with rationing, indoctrination and fear. That home exists on the other side of the border: a Moroccan Sahara which, with all its imperfections, offers stability, tangible investments and a recognisable legal framework.

Remaining silent in the face of the exploitation of human beings is complicity. That is why this article raises its voice to remind us that return is not a negotiable privilege: it is a right that has been taken away and must be restored urgently. As long as the international community continues to feed the mirage of Tindouf, it will continue to prolong the tragedy. And every day that passes without concrete solutions will be another day of innocent people condemned to a life in limbo under the scorching sun of the Algerian desert.

History will judge those who, having the power to act, chose to look the other way. Today, we still have time to take the right side: the side of freedom, dignity, return home and the reunification of Sahrawi families fractured in the past. Because justice delayed, here as elsewhere, is justice denied.