The war against the women in Sudan

This document is a copy of the original that has been published by the Spanish Institute of Strategic Studies at the following link

Introduction

This analysis outlines the background to and current situation of the armed conflict that is bleeding Sudan, and then focuses, from a feminist perspective, on the suffering and struggle of Sudanese women in this terrible situation.

To this end, the present paper is organised around four points to approach and understand the reality of the country: a description of the crisis, the population movements resulting from it, the terrible impact on women’s welfare and survival, and last, some examples to illustrate that the traditional struggle of Sudanese women for peace is ongoing, despite the difficulties.

The crisis in Sudan

Note on the regional background

The regional context of Sudan, which borders the Red Sea and includes the Sahel region and the Horn of Africa, is one of high volatility and instability. In the last five years, five countries bordering Sudan have suffered and are still suffering from armed conflict or political unrest within their borders, namely Ethiopia, Central African Republic, Chad, Libya and South Sudan. It is because of this regional instability that the Sudanese conflict materialised by the dispute between Generals Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo is setting off alarm bells beyond the country’s own borders.1

Bankole Adeoye, head of Political Affairs, Peace and Security at the African Union, goes even further, arguing that it is imperative to halt Sudan's slide towards total collapse with its undoubted devastating repercussions for the region, the African continent and the world as a whole.2

To grasp the gravity of the situation, it is useful to look at the specific circumstances in both Sudan itself and in the region.

Notes on Sudan

Much of the country is poverty-stricken with ongoing emergency situations, including famine. It is estimated that more than 7 million people in Sudan live with severe food insecurity.3

Notably, in the political sphere, the last decades of the country's recent history have seen alternation between multi-party parliamentary systems and dictatorships, punctuated by numerous armed conflicts, not only between North and South Sudan, with the milestone of South Sudan's independence in 2011, but also between regions in the North in competition for resources and along ethnic, socio-cultural and religious divides.4

While it is, therefore, a country with a historical succession of inequalities and struggles, the current one stands out as one of the most virulent socio-economic crises in its history.

The Republic of Sudan is currently in a so-called transitional phase towards elections in 2024, following the overthrow of the dictatorship of Omar al-Bashir, with a civilian-military government led by Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok and the Sovereign Council.

This scenario is being disrupted by the armed conflict between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) led by Abdelfatha al Burhan, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemeti. Open fighting broke out on 15 April and its epicentre of destruction is the capital, Khartoum.

The aim of both SAF and RSF is to maintain control over the power structure. There does not seem to be any ideological component behind this intention beyond the material gain.5 This is, in a sense, an attempt to flee from a bad situation because behind its apparent objective lies, among other motivations, the avoidance of responsibility for actions such as the massacres in Darfur, for which the leaders of both groups have been accused.6

The abyss the country is facing is difficult to avoid, given the convergence of such real factors as the acute economic crisis, the still-open wounds after decades of armed conflict, international interests and the strength of the military actors in the conflict.

The situation could potentially lead to the collapse of the continent's third largest country, where a third of the population is already dependent on humanitarian aid.

Last May there were a few days of ceasefire, which was not fully respected but did calm the fighting slightly, allowing access for humanitarian aid.7 Despite attempts to extend the ceasefire, the conflict continues unabated at the time of writing (9 June 2023).

In this context of drought, bank closures due to lack of liquidity, high food and fuel prices and the devastating effects of any conflict such as population movements, all of which is compounded by previous inequalities, the situation of women is recognised as one of vulnerability.

Population movements

Sudan is one of the countries that has traditionally had the highest number of internally displaced persons (IDPs). Although numbers have dropped since the secession of South Sudan,8 they are still overwhelming.

9 It is estimated that more than 300,000 people have been displaced within the country and more than 100,000 outside it since the conflict began just two months before the time of writing.10 Estimates of the number of people that have left Sudan - both Sudanese and refugees and migrants from other countries such as Chad, South Sudan11 and Ethiopia (Sudan hosts one of the highest numbers of migrants on the continent12) - stand at more than 100,000, and this figure may increase eightfold if a solution is not reached soon.13

The impact of the conflict on women

In this document, women will be understood to be females over the age of eighteen, and girls will not be considered because, although they are also disproportionately affected by conflict, they are a different group linked to other life stages.

Initial situation

In the 1970s, under Colonel Gaafar Al Nimeiry - who ruled the country from 1969 to 1985 a process of introducing laws from the perspective of religious precepts and mandates took place. In this period, ultra-conservative laws on public and family morality permissibly codified issues such as child marriage, male guardianship over females and genital mutilation.14

It is shocking in this context that women's suffrage was introduced in Sudan in 1965, when in Spain women were allowed to vote during the Second Republic but were then not allowed to vote until 1977. This measure of electoral openness and the modification of discriminatory laws was thanks to the work of the Sudanese Women's Union in defence of women's rights, founded in 1952. In 1989, when Al Bashir came to power, the organisation had to officially disband, although it remains in exile in London.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW),15 adopted by the United Nations in 1979, is the most comprehensive international agreement on women's basic human rights. To date it has not been ratified by Sudan. The reason argued by those in power since then is that Sudan has its own context to which indigenous culture and religion are more responsive. The solution is seen as Islam rather than the adoption of Western legal frameworks.16

To this effect, the Shari'a, the Islamic legal system, was adopted as a legal source even before the country's independence. Later, under the Al Bashir regime, the Islamisation of the country's legal system began. In 1991, the first family law was passed. Until that time, the Shari'a had governed these matters.

The 1991 law legalised child marriage and male guardianship, requiring a wife's obedience to her husband and denying women access to work outside the home without the permission of their male guardian. It is the most conservative Muslim family law in the region.17

This Islamisation of laws brought about ethnic and class hierarchisation, reinforcing multiple discrimination. By way of example, unqualified women are not allowed to work in the evenings and nights, but women who are qualified are.18 There are also racial hierarchies where the preferred skin colour is the lightest, the darkest being associated with the legacy of the slaves. To be a woman in Sudan is to be less, but to this can be added aggravating factors such as social status, religion and skin colour - which is why skin bleaching is a common practice in the country. 19

The so-called public order laws adopted under the al-Bashir regime restricted women's movement and dictated dress in public spaces, forcing women to submit to "piety and modesty". One of the first actions of Prime Minister Abdallah Hammdok's cabinet (2019- 2021) was to abolish these laws.

However, women still face discrimination and severe difficulties. For these reasons, they are particularly vulnerable to gender-based violence and, unable to find safety inside or outside their homes, they are subjected to sexual violence daily.

Sexual violence finds fertile ground in Sudan where neither forced marriage nor marital rape is illegal.

Within the government apparatus itself, however, there is a department in charge of combating violence against women according to the legal framework, i.e. without prosecuting all the above-mentioned non-criminalised violence. This is the Combating Violence Against Women Unit (CVAW), which reports to the Sudanese Ministry of Social Affairs.

Two years ago, in 2021, this ministerial unit published a working paper20 drawn up with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the first in Sudan with a national focus on gender-based violence. It states that the community perceives the restrictions on movement for women and girls and domestic and sexual violence against women as common problem, especially physical violence in the home by husbands against wives and by brothers against sisters. Sexual violence is perceived as a phenomenon that particularly affects women in informal jobs, refugee and displaced women, and women with disabilities, especially those with mental disabilities.

One form of violence that is particularly prominent in Sudan is honour killings, which have been increasing in number for years. Female adultery was criminalised in the 1991 Penal Code and justifies sentences of death by stoning.21

Situation of women due to the armed conflict

Women experience a variety of situations of hardship and life-threatening risks in armed conflict. In this respect, UN Security Council Resolution 1325 recognises that war and armed conflict have a disproportionate impact on them as they are often used by the warring parties.

Expressing concern that civilians, particularly women and children, account for the vast majority of those adversely affected by armed conflict, including as refugees and internally displaced persons, and increasingly are targeted by combatants and armed elements, and recognising the consequent impact this has on durable peace and reconciliation.

Reaffirming the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts and in peacebuilding, and stressing the importance of their equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security, and the need to increase their role in decision-making regarding conflict prevention and resolution".22

The civilian population, and women, are caught between the warring sides. In this case between the Sudanese Army (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), with their corps often included within what could be considered the battlefield.

On 27 May, the Unit to Combat Violence against Women reported 24 cases of sexual violence in Khartoum and 25 in Darfur. While these reports identify RSF members as the main perpetrators of these crimes, one side in fact accuses the other. It seems coherent to believe that both could be telling the truth.

The difficulties women face is multiplied by the lack of medical care available due to the bombing. The damage to most hospitals in Khartoum, and the shortage of medicines, poses a high risk to the lives of survivors of sexual violence and pregnant women in need of care.23

Not surprisingly, the bombings in Khartoum on the night of 15 April had a profound impact on the health of pregnant women.24 The impact of armed conflict on this group is profound and multifaceted. Among many other factors, war increases anxiety, which can lead to premature births, low birth weights and other complications.25

Another often overlooked risk factor for women's health is the shortage of sanitary products for menstrual care. Add to this problem of hygiene the increasing scarcity of water, and women's health is seriously compromised.

Other health structures and resources, e.g. for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, which were precariously in place before the conflict, have disappeared from the population's reach because of the conflict.

Hand in hand with the increased scarcity of resources of all kinds, as in any conflict, we find an increase in all kinds of violence. Another investigation points to the RSF as being responsible for much of it. According to one report,26 carried out by the non-governmental organisation Human Rights Watch, the Rapid Support Forces have carried out systematic violations in many towns and villages. It is nothing new for this paramilitary force to commit crimes of this kind.

The seed of the current RSF lies in the Arab paramilitary militia called Janjaweed, formed by the Sudanese government during the second Chadian civil war (1979-1982), to prevent Chadian incursions into Sudanese territory.

Institutionalised as RSF, it was charged with carrying out ethnic cleansing operations that included the systematic rape of women.27 Throughout the revolution, RSF actions included house raids, killings, torture and rape. It is estimated that more than 70 rapes were committed by paramilitary forces during the 3 June 2019 massacre in Khartoum alone.

Since the December 2018 Revolution, sexual violence against women has been used repeatedly to resolve political conflicts in Sudan.28 Sexual assaults against women have been increasing in number for years. These terrible practices have become a trend, and women in Khartoum are once again suffering the scourge of sexual violence perpetrated by RSF members.

As mentioned above, while dozens of sexual assaults are being documented it is estimated that their real number is and will be much higher. The attacks appear to be perpetrated by RSF and opportunistic criminal gangs operating with impunity,29 mainly in Khartoum and Darfur. Cases of abducted and disappeared women are also documented. Sulaima Ishaq, head of Sudan's Unit for Combating Violence against Women, estimates that the documented cases account for 1% to 2% of those actually taking place in Khartoum.

Security in public spaces no longer exists, while the scarcity of food and water is forcing people to move further afield, putting them at high risk of attack. "For women in Khartoum and Darfur it is a very alarming situation; it is always women who pay the price for a war waged by men," says Sulaima Ishaq.30

Since the military takeover, the welfare and even the very survival of women in Sudan has therefore been progressively compromised. The gains that Sudanese women have been able to make in the struggle for their rights since the start of the revolution in 2018 are likewise under threat.31

Many families find themselves at the mercy of armed men, even within their own homes, which they are sometimes forced to share with members of the RSF, with the added danger of being a woman in this situation.

And the alternative is no better. Population movements are commonplace, especially of mothers with children, but this situation of greater vulnerability does not mitigate the risk of suffering different forms of gender-based violence. So, there is no escape. More than half the world's refugees are women and children, highlighting the disproportionate impact of violence on women.

Women's struggle for peace

A significant feature in the history of the people of Sudan, and one that distinguishes it from many of its regional neighbours, is the non-violent popular uprisings. Notable in this respect are the October 1964 Revolution, which put an end to General Abboud's military government, and the April 1985 uprisings to overthrow al-Numeiry.

The third historic moment of non-violent popular uprising for a political transition to civilian rule in Sudan is known as the December Revolution, which culminated in the formation of a transitional government in August 2019 following the overthrow of Al Bashir a few months earlier.

"Women's opposition to the Al Bashir regime is fundamental to understanding their strong involvement in the revolution," says Liv Tønnessen, a political scientist specialising in gender and Sudanese politics at the Christian Michelsen Institute in Norway.32

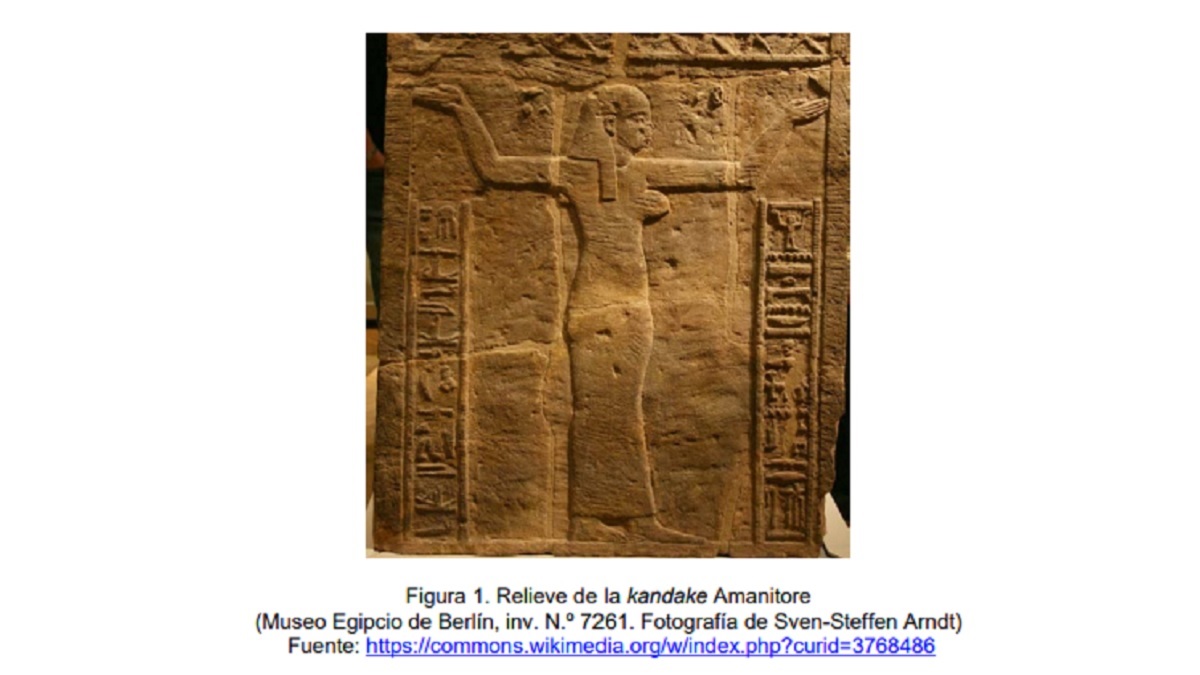

Women in Sudan were at the forefront of the massive popular mobilisations that led to this change. Their participation attracted considerable international attention. These women were called kandakes, after the powerful Nubian queens.33 The other face of these mobilisations was more internal, often taking place in open defiance of rigid, patriarchal family environments, and key to shaping the neighbourhood resistance committees and professional associations that led the revolution and later became the heart of the country's democratic movement.34

Avoiding a repeat of this female protagonism could be the aim of the current strategy of violence against women. Samia El Nagar, a Sudanese researcher, agrees. She believes that the purpose of this violence is to sow fear in families to prevent young women from mobilising.35

Regardless of the hypothetical intention behind the actions of unconscionable violence against women, what is not in question is the devastating impact of the Sudanese conflict on women. This dynamic of violence against women in armed conflict is ubiquitous and universal, with few exceptions, and draws on pre-existing socio-cultural roots of inequality. The struggle of Sudanese women to make their voices heard in efforts to achieve and build a stable and lasting peace is likewise nourished by previous dynamics.

Women have been mobilising in Sudan for many years. However, while this armed conflict is no exception in this regard, we do find an essential structural difference in the current situation: division.

The women's movement is divided by intergenerational conflicts, ideological differences and, most seriously, by the division between feminists who challenge power dynamics and women who, in exchange for perks, serve the patriarchal powers that be.36

With these divisions in mind, or despite them, we can highlight a number of governmental and non-governmental women's initiatives and organisations that are of particular significance in the country: Women of Sudanese Civic and Political Groups (MANSAM), the Sudanese Women's Union, and the NO to Oppression against Women Initiative.

Women of Sudanese Civic and Political Groups (MANSAM)

MANSAM is an alliance of eight women's political groups, 18 civil society organisations, two youth groups and individuals not affiliated to any organisation, which played a leading role in the December 2018 Revolution. Despite this, only one woman took part in the peace negotiations.37

This group grew to become the largest women's coalition in the country. However, the divisions discussed above soon began to manifest themselves, and some subgroups left the coalition as their political interests clashed.

Despite the divisions, MANSAM is still very much alive and looks set to remain a key player in the destiny of the women's movement, despite its fractures, and will be instrumental in securing the country's path to democracy and lasting peace.38

Sudanese Women's Union (SWU)

Founded in 1952, it is one of the largest women's rights organisations on the continent. Their history highlights their struggle for education and against child marriage and non- consensual marriage, for the regulation of polygamy, against discrimination in the workplace and against the obligation of abused women to return to their husbands.

During Al Bashir's rule, it had to officially disband, continuing its work from exile in London. It was therefore Sudan's own political landscape that prevented the development of a strong women's movement by excluding women from leadership positions, and by the political parties' monopolisation of women's issues and women's rights. 39

No to Oppression Against Women Initiative

This initiative was formed in 2009 and calls for change in Sudanese laws that discriminate against women. Today, despite the persecution to which it is subjected, its main objective is to defend women's rights by monitoring violations and supporting victims.

Since the 25 October coup, Sudan's security services have been hunting down political activists and civil society leaders. These arrests are aimed at curbing the activities of opponents of the coup and impeding the popular movement demanding the removal of the military from political power.40

New organisations

On 12 May 2023, the Office of the African Union Special Envoy for Women, Peace and Security, with the support of UN Women and the African Women Leaders Network (AWLN), and in coordination with the Peace for Sudan Platform, organised a virtual meeting to support and give a voice to the work for peace in Sudan.41

At the meeting, Lina Marwan, a feminist and rights lawyer and member of the Peace for Sudan Platform, listed some of the many newly formed women's organisations that are springing up both in Sudan and in the diaspora to work for peace:

- Women Against the War

- Women's call to Resist War and Demand its End Initiative (Kordofan):

- Mothers of Sudan the Cease Fire Initiative of Darfur,

- South Red Sea Organizations' Initiative:

- Gadaref Emergency room (East Sudan)

- Northern state Emergency room

- Mothers of Al Gazira Solidarity for Shelters (Middle States)

- Bit Al Mal Women's Cooperative Association (Omdurman)

- Women and Children Organization for Development and Peace (Eastern region)

This list, without any need for further elaboration, serves as an auspicious example that women still have a central role in supporting the community in the most difficult situations, despite their peripheral position in areas of power.

For Hala Al-Karib, regional director of the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa, the international community should also be more forceful with the warring parties and place accountability at the heart of its action in Sudan.42 Perhaps if the call were to reach women's organisations in the international community, the voice of sisterhood would make itself loud enough to be heard.

Conclusions

Women have traditionally been particularly affected by armed conflict. Nevertheless, or precisely because of this, they can and do play an essential role in all areas of peace work. The case of Sudan is particularly illustrative in this regard.

In Sudan, women not only have to deal with this direct violence, but its onslaught spreads to other fronts such as access to food, water and medical care. This is an extremely serious context that requires urgent international action to ensure women’s safety and well-being.

Despite the great difficulties and the abyss that the country seems to be facing, it is not unreasonable to think that now more than ever is the time for Sudanese women to lead - should they be allowed to. Powerful domestic actors are not on board, so it is time for international organisations to work in support of a struggle and a leadership that is already under way.

Peace must not be satisfied with stopping the war, but must help to heal the wounds, to recover what was lost and to build what does not yet exist. Peace is much more than the absence of war.

Because when the war comes to an end, it will not be possible to build a firm and lasting peace in the absence and exclusion, once again in human history, of half the population with all its talents and abilities.

References:

1 MÁRMOL, Alba. "Conflict in Sudan threatens its neighbours', El Periódico de España, 21/05/2023. Available at: Sudan | Conflict in Sudan threatens its neighbours | El Periódico de España (epe.es)

2 UNITED NATIONS. NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL. "Continued Military Hostilities between Warring Parties Endanger Thousands of People, Sudan's Future, Region, Briefers Tell Security Council", Meeting 9326, SC/15291. 22 May 2023. Available at: https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15291.doc.htm

3 INTEGRATED FOOD SECURITY PHASE CLASSIFICATION. Available at:

IPC Country Analysis | IPC - Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (ipcinfo.org)

4 TØNNESSEN,Liv. "Sudan" in the Middle East; LUST, Ellen; CQ Press,16th ed. February 2023. Available at: 8357-sudan.pdf (wcc.no)

5 ALLAH, Samah Khalaf and DOLEEB, Afaf Doleeb. "Sudan's turmoil: Revolution, power struggles, and the quest for stability", Chr. Michelsen Institute, April 2023. Available at: Sudan's turmoil: Revolution, power struggles, and the quest for stability (cmi.no)

6 Ibid.

7 EFE, "New ceasefire agreement in Sudan mediated by Saudi Arabia and the US", 21 May 2023. Available at: https://www.elmundo.es/internacional/2023/05/21/6469bae1fc6c83807b8b45ae.html?utm_campaign=dos ier-lunes-22-de-mayo-de-2023&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail

8 TØNNESSEN, Liv. (2023) p.9. Op. cit.

9 UNITED NATIONS. UNHCR. "Population Movement from Sudan (as of 1 May 2023)", May 2023. Available at: Document - RB EHAGL | CORE Week 01 - Population Movement from Sudan (as of 1 May 2023) (unhcr.org)

10 BELLAMY, Daniel. "Hundreds of refugees cross into western Ethiopia from Sudan every day", Africanews, 20/05/2023. Available at: https://www.africanews.com/2023/05/20/hundreds-of-refugees- cross-into-western-ethiopia-from-sudan-every-day/?utm_campaign=dosier-lunes-22-de-mayo-de- 2023&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail

11 HALLQVIST, Charlotte. "Les violences au Soudan forcent les réfugiés du Soudan du Sud à rentrer au pays", UNHCR, 15/05/2023. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/fr/actualites/articles-et-reportages/les- violences-au-soudan-forcent-les-refugies-du-soudan-du-sud

12 VV.AA. "Mixed migration consequences of Sudan's conflict", Mixed Migration Center, 04/05/2023. Available at: https://mixedmigration.org/articles/mixed-migration-consequences-sudan-conflict/

13 AL JAZEERA. "UN refugee agency warns more than 800,000 may flee Sudan", 01/05/2023. Available at: UN refugee agency warns more than 800,000 may flee Sudan | News | Al Jazeera

14 ESPAÑOL, Marc. "Los derechos de las mujeres, en jaque tras el golpe de Estado en Sudán", El País, 28/01/2022. Available at: https://elpais.com/planeta-futuro/2022-01-28/los-derechos-de-las-mujeres-en- jaque-tras-el-golpe-de-estado-en-sudan.html

Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) | OHCHR

16 TØNNESSEN, Liv. "Between Sharia and CEDAW in Sudan: Islamist women negotiating gender equity" in SIEDER, Rachel Sieder and McNEISH, John: Gender Justice and Legal Pluralities: Latin American and African Perspectives. New York: Routledge-Cavendish, 2013. p. 133.

17 EL NAGAR, Samia and TØNNESSEN, Liv. "Family law reform in Sudan: competing claims for gender justice between sharia and women's human rights", p.9, CMI report, number 5, December 2017. Available at: https://www.cmi.no/publications/file/6401-family-law-reform-in

18 Ibid. p. 21.

19 TØNNESSEN, Liv. (2023) p.9. Op. cit.

20 UNITED NATIONS. UNITED NATIONS POPULATION FUND SUDAN. "Voices from Sudan 2020: A

qualitative assessment of gender based violence in Sudan". 07/2021. Available at: https://sudan.unfpa.org/en/publications/voices-sudan-2020-qualitative-assessment-gender-based- violence-sudan

21 INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION FOR HUMAN RIGHTS "Solidarity with Amal, Sudanese girl sentenced to death by stoning", 19/10/2022. Available at: Solidarity with Amal, young Sudanese woman sentenced to death by stoning (fidh.org)

22 UNITED NATIONS. UNITED NATIONS SECURITY COUNCIL. “Resolución 1325”, 2000. Available at:

Resolution1325, 2000. S/RES/1325 (unhcr.org)

23 ABBAS, Rem. "Women on the Frontlines: A Feminist Perspective on the Ongoing Crisis in Sudan', ReliefWeb, 26/04/2023. Available at: Women on the Frontlines: A Feminist Perspective on the Ongoing Crisis in Sudan - Sudan | ReliefWeb

24 ALLAH, Samah Khalaf. Op. cit.

25 TORCHE, Florencia and VILLAREAL, Andrés. "Prenatal Exposure to Violence and Birth Weight in Mexico: Selectivity, Exposure, and Behavioral Responses" 19/08/2014. American Sociology Review, Volume 79, Issue 5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414544733

26 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH. "Men With No Mercy" Rapid Support Forces Attacks against Civilians in Darfur, Sudan", September 2015. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/09/09/men-no- mercy/rapid-support-forces-attacks-against-civilians-darfur-sudan

27 TØNNESSEN, Liv. (2023) p.9. Op. cit.

28 HABANI, Amal. "Sudanese Women's Bodies: Not Battlefields for Political Conflicts", Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, 16/03/2023. Available at: Sudanese Women's Bodies: Not Battlefields for Political Conflicts - Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

29 ESPAÑOL, Marc. "Migrantes etíopes violadas en grupo y otros crímenes contra las mujeres al calor de la impunidad y el caos de Sudán", El País, 06/06/2023. Available at: Ethiopian migrants gang-raped and other crimes against women in the heat of impunity and chaos in Sudan | Planeta Futuro | EL PAÍS (elpais.com)

30 Ibid.

31 ESPAÑOL, Marc. "Los derechos de las mujeres, en jaque tras el golpe de Estado en Sudán", El País, 28/01/2022. Available at: Women's rights: Women's rights in check after the coup d'état in Sudan | Planeta Futuro | EL PAÍS (elpais.com)

32 ibid.

33 ABUSHARAF, Rogaia. "The women of Sudan will not accept setbacks", Brookings, 03/03/2022. Available at: The women of Sudan will not accept setbacks (brookings.edu)

34 ESPAÑOL, Marc. (2023). Op. cit.

35 ESPAÑOL, Marc. (2023). Op. cit.

36 ALLAH, Samah Khalaf. Op. cit.

37 SALAH, ALAA. "Statement by Ms Alaa Salah at the UN Security Council Open Debate on Women, Peace and Security", 04/11/2019. NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security. Available at: Statement by Ms. Alaa Salah at the UN Security Council Open Debate on Women, Peace and Security - NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security (womenpeacesecurity.org)

38 GEORGE, Rachel A., "Resolving Sudan's Crisis Will Require Inclusive Peace", Council on Foreign Relations, 05/06/2023. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/blog/resolving-sudans-crisis-will-require-inclusive- peace

39 ABBAS, Rem. Op. cit.

40 ALTAGHYEER. "Sudan: Head of "No to the oppression of women" initiative arrested, whereabouts unknown", 23/01/2022. Available at: Sudan: Head of "No to Oppression against women" initiative... - AlTaghyeer

41 UNWOMEN AFRICA. "Presentations of the Sudanese Women "Peace for Sudan Platform". High level Meeting of Leaders in Solidarity with Women of Sudan. May 12, 2023. Virtual Meeting". Available at: https://africa.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/ENG%20IGAD%20UN%20Women%20FINAL.pdf

42 ESPAÑOL, Marc. (2023). Op. cit.