The frozen geopolitics: an expanding chessboard in the Arctic (I)

In recent years, we have devoted many articles to discussing the Arctic and its geostrategic importance, and today we consider it interesting to turn our attention to an area that is gaining prominence and will be the epicentre of international disputes and interests.

The Arctic, previously considered a remote and peripheral region on the global geopolitical chessboard, is becoming a focus of growing strategic, economic and environmental interest. Progressive melting, caused by climate change, is opening up new shipping routes, revealing vast natural resources that are realistic and profitable to access, and exacerbating tensions between circumpolar nations and extra-regional actors.

In this paper, we aim to delve deeper into the complex geopolitics of the Arctic, analysing its main actors, the disputes that divide them and the implications for the future of this crucial region.

There are two main definitions of the Arctic. The first refers to the region of the northern hemisphere where the sun does not rise during the winter solstice and does not set during the summer solstice. It is currently a circle marked on the map at latitude 66º 34' (although it shifts slightly each year). This area covers approximately 4% of the Earth's surface. It should be noted that not all of this territory remains under ice throughout the year. The Arctic Circle is (to describe it in a crude way) a sea surrounded by land. The sea absorbs solar radiation and retains heat, raising the temperature of the entire region. Scandinavia and Norway in particular are also warmed by the Gulf Stream. The net result is that some places within the Arctic Circle can have warm summers with temperatures of up to 30ºC.

The second refers to a region where the average temperature of the warmest month is below +10ºC. This definition roughly corresponds to the Arctic Circle across Alaska, Canada and Russia, although most of it lies within it. In the Scandinavian countries, this zone only applies to a small portion of the northernmost part of Norway. There are two large protrusions that extend beyond the Arctic Circle: one extends to the Bering Sea and the other includes Iceland, Greenland and Hudson Bay.

However, once the area has been defined from a geographical point of view, an issue arises which, although it may seem minor, is not. This is how this region is defined and named in geopolitical terms; specifically, we are going to discuss what is known as the ‘High North’.

The concept of the ‘High North’ has become highly relevant in current geopolitics, especially in NATO debates, but what does ‘High North’ mean?

The ‘High North’ is a term that broadly describes the Arctic region, but it is not that simple. The term includes any land or sea located within the Arctic Circle, but also any adjacent area of strategic importance, for example, the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) gap, a maritime region between Iceland and the United Kingdom that controls access to the Atlantic for any Russian vessel launched from within the Arctic. The phrase was first coined by Sverre Jervell in his 1986 book ‘The Military Buildup in the High North’. Jervell (a Norwegian diplomat) does not give a definition in the book, but the idea is widely identified with the Arctic.

In the current geopolitical context, the importance of the ‘High North’ is such that, in the review of the Alliance's regional defence plans following the invasion of Ukraine, one of them is devoted exclusively to the area described by this term. What is more, a third JFC (Joint Force Command) has even been created, based in Norfolk, USA, responsible for operations in the area.

That is why, when the term ‘High North’ is used in Alliance circles and meetings, it refers to the Arctic region and adjacent sub-Arctic areas. In short, the concept, which has no strictly defined geographical boundaries, encompasses:

- The Arctic Ocean: including its marginal seas such as the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea, the Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea and the Chukchi Sea.

- The surrounding lands and islands: such as Greenland, Iceland, northern Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden and Finland), northern Russia and parts of northern Canada and Alaska.

Now that we have clarified this concept, which is key to understanding the growing interest in the region, we will mention the key factors behind it:

- Climate change: global warming is reducing the Arctic ice mass, allowing icebreakers to be more effective and opening up new shipping routes, or, to be more precise, making them safe to navigate for longer periods of time (such as the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route). Similarly, removing ice from some areas facilitates access to natural resources.

- Natural resources: what were estimates not so long ago are now a proven reality. The region contains significant reserves of oil, natural gas, minerals, rare earths and fishing resources.

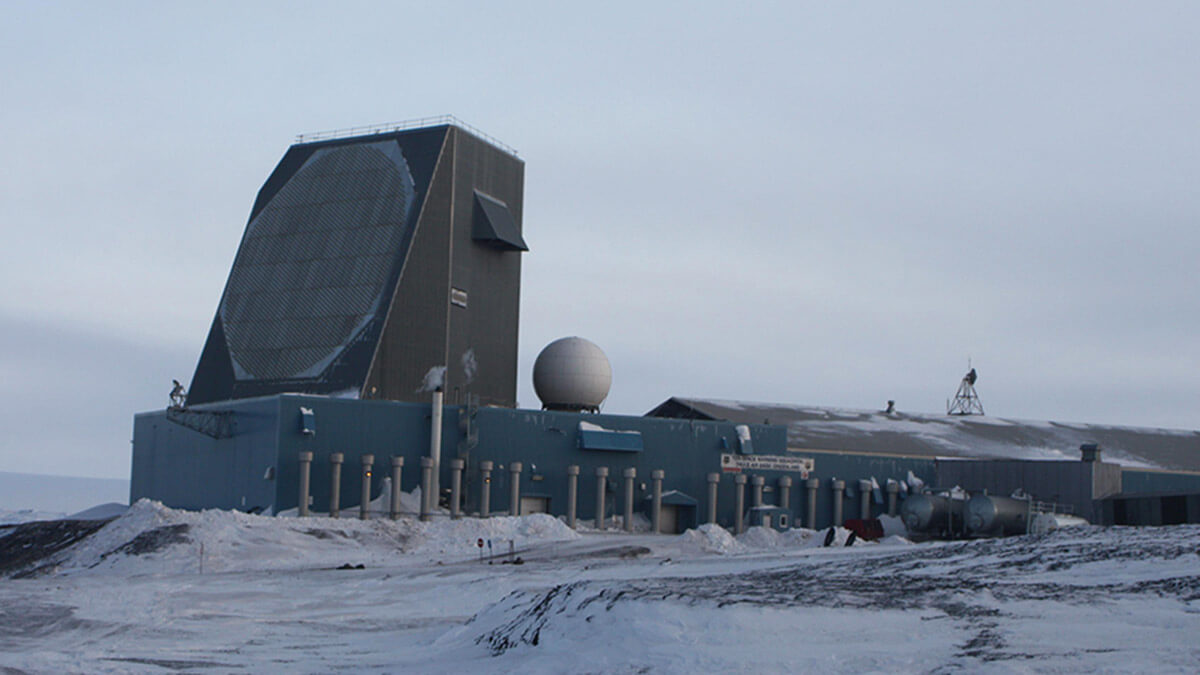

- Strategic importance: this is dictated by geography. The area is located right between major powers (the United States, Russia and China), is the shortest route between them and is of enormous importance for the deployment of defence and early warning systems.

- Geopolitical rivalry: the current race and growing competition for resources of all kinds, especially those essential for technology, and attempts to increase influence in the region have led to greater attention from state and non-state actors.

- Security implications: the changing Arctic environment poses new security challenges. Increased maritime activity, competition for resources and the militarisation of the region are causes for concern, as they create a growing sense of instability and increase the likelihood of conflict.

- Global environmental impact: The Arctic region plays a crucial role in the global climate system. Glacial melt and the release of methane trapped in permafrost have significant implications for sea level rise and global climate change. This means that interest in the area is not limited to those countries with direct geographical access to it.

Melting ice as a catalyst for geopolitical change

For centuries, the Arctic and part of the surrounding regions have remained inaccessible due to harsh climatic conditions and permanent ice cover. Rising global temperatures have reduced the ice mass at certain times of the year. This climatic phenomenon, along with others of various kinds, has triggered changes that have directly impacted the geopolitical profile of the region, placing it among the key points on the planet.

The main players on the ‘High North’ chessboard

There are eight Arctic nations: Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the United States. These are the countries with territory in the Arctic Circle and all are members of the Arctic Council, a body created in 1996 to promote cooperation in the area.

Of all these countries, Russia has the longest Arctic coastline and a long history of presence in the region. It considers the Arctic to be an area of vital strategic importance and has invested significantly in military and civil infrastructure there in order to secure its economic interests (mainly hydrocarbons and the Northern Sea Route) and because of its importance for the projection of its power. Russia has reopened Soviet-era military bases, modernised its northern fleet and conducted regular military exercises in the region, causing concern among other actors.

Canada, for its part, claims a vast area of the Arctic, including parts of the Northwest Passage. Its strategy focuses on territorial sovereignty, environmental protection and the sustainable development of indigenous communities. Gradually, and especially since the events in Ukraine, it has strengthened its military presence in the area, albeit on a smaller scale than Russia, while always seeking to emphasise the importance of international cooperation. The question of sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, which Canada considers internal waters and other actors consider an international sea lane, remains a key point of tension.

Through Alaska, the United States is also an Arctic nation. Its focus has historically been on defence and scientific research. However, due to growing interest in resources and shipping routes, the United States has begun to pay closer attention to the region, updating its strategic vision for the area and significantly increasing its military presence. The main limitation for the United States, surprising as it may seem, is the lack of a modern icebreaker fleet that would allow it to increase its freedom of movement and enhance its power projection capabilities.

Norway shares a border with Russia in the Arctic and administers the Svalbard archipelago, a demilitarised territory with special status. Its strategy is based on a balance between resource exploitation (mainly oil and gas in the Barents Sea), environmental protection and international cooperation. Norway has always maintained a cautious but firm stance in its interactions with Russia in the region.

The Kingdom of Denmark has a significant presence in the Arctic through Greenland, which is very much in the news following Trump's arrival in the White House, the world's largest island, which enjoys extensive autonomy, and the Faroe Islands. Greenland has significant mineral resources and its economic potential is attracting growing interest. Denmark focuses on scientific cooperation, environmental protection and support for the sustainable development of Greenland. Whatever happens to Greenland in the future, as there is an independence movement on the island, it could reshape the Arctic geopolitical landscape.

Alongside the Arctic nations, other extra-regional actors have shown growing interest in the Arctic, including China, the United Kingdom and even Japan, to which supranational entities such as the EU must be added.

The United Kingdom, ‘the Arctic's closest neighbour’ (as the British government calls itself because it is the country with the closest territory to the Arctic Circle, but not within it), has traditionally shown a deep interest in the region, together with the Netherlands, to such an extent that during the Cold War it stationed a large part of its naval forces and all of its amphibious forces in the ‘High North’, and even today it continues to conduct routine exercises in Norway, including within the Arctic Circle.

The role of China, so often discussed in these pages, is more than relevant. China calls itself a ‘quasi-Arctic state’ and has expressed great interest in the economic and scientific opportunities offered by the region. Its strategy focuses on scientific research, investment in infrastructure (especially in Russia), and the promotion of the ‘Polar Silk Road’ as an extension of its Silk Road Initiative and the String of Pearls. China's growing presence in the Arctic has raised concerns among circumpolar nations, which are wary of its long-term intentions and potential influence.

Also worth mentioning are the three Baltic countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. None of them are in the Arctic Circle, but it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which a conflict breaks out in Scandinavia and the Baltic states are not involved, and vice versa.

Thus, the concept of the ‘High North’ is proving to be flexible and can be used to encompass both the Arctic and adjacent regions. It cannot be ignored that it is not only the Arctic nations that have interests in the region and that we are referring to what is probably, from a geopolitical point of view, the most decisive region on the planet, as it is where the interests of all the major powers and relevant actors converge.