The Mediterranean in transformation: the strategic alliance between Rabat and Madrid

The issue does not lie in the agreements signed or the formal photographs calmly captured by photographers, but in the hidden dynamics at work within the structure of the Moroccan and Spanish political minds alike, as if both were entering a laboratory of self-criticism once again after decades of tensions and unproductive reactions.

Madrid welcomed not only a Moroccan government delegation, but also all the transformations that the region has undergone since the fall of the wall of stability in the Middle East after 7 October, and the consequent redefinitions of maps and alliances, in a Mediterranean that has become an exposed mirror of the clash of wills.

This raises the crucial question: why is this summit being held at this particular moment? Why is Spanish support for the autonomy initiative being reaffirmed while the world is rushing towards new conflicts between East and West? Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that Madrid discovered – after years of hesitation – that betting on Morocco was no longer a tactical option but had become a strategic necessity to protect its southern border and avoid future fractures in an international environment that is changing at an alarming rate.

Madrid's support for the autonomy initiative is not just a political gesture, but an implicit recognition that the artificial conflict in the Sahara is no longer solely regional and has become a gamble on who has the capacity to generate stability in an environment where networks of terrorism, crime and irregular migration operate, issues that, as Spain knows better than anyone, are not handled with soft rhetoric, but with solid alliances.

For its part, Morocco understands that the door to southern Europe can only be opened through Spain, just as Madrid knows that the pulse of the new Africa can only be reached through Rabat.

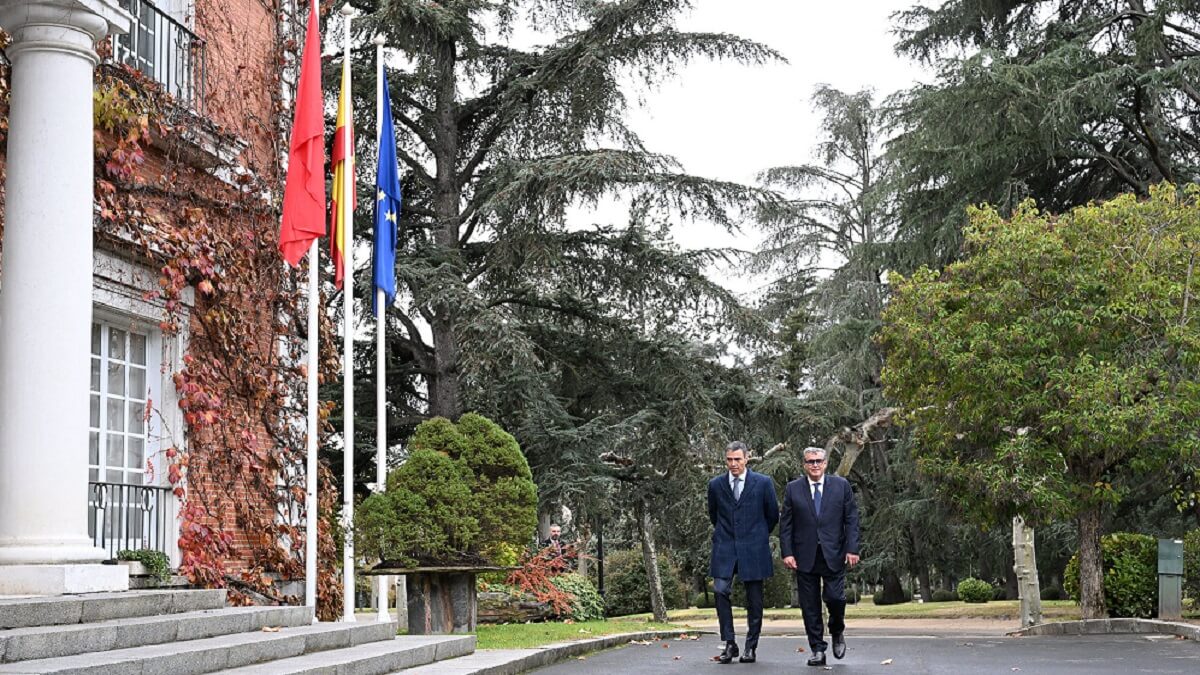

This organic interconnection between the two sides explains why Madrid, for the first time in decades, has declared that current relations are ‘the best in history’. A seemingly simple phrase, but one that essentially means that both countries have finally decided to break the historical chain that has long hindered any joint momentum towards the future.

The agreements signed in Madrid are not mere technical documents, but the construction of an infrastructure for a new political mindset: cooperation in agriculture and fisheries, the fight against extremism, digitalisation, taxation, education, sport, diplomatic exchange and the preservation of archives and memory. It is as if both countries understood that future conflicts will not be resolved with armies, but with a digital port, a diplomatic school or a legal platform capable of generating knowledge rather than recycling it.

It is striking that the thirteenth summit coincided with the Security Council's renewed support for the autonomy initiative for the Sahara, reflecting a profound shift in the balance of international legitimacy, where the separatist trend has been overshadowed by geopolitics, while the idea of a realistic and gradual solution is gaining ground over the revolutionary illusion that only produced stagnation, displacement and frustration.

There is also another crucial dimension: the real dynamic between Rabat and Madrid. The excellent relationship between King Mohammed VI and King Felipe VI is not a matter of protocol, but a fundamental element in building a trust that governments alone could not establish. This balanced and serene relationship has been and continues to be a guarantee for a new phase of deep coordination, especially with the approach of the 2030 World Cup, which will turn the Mediterranean into a laboratory of development where investment, infrastructure, culture, sport and politics will intertwine.

In this context, a bigger question arises: can the Mediterranean really become an area of shared stability between Rabat, Madrid and Lisbon at a time when traditional alliances are breaking down? Perhaps it can, if both countries manage to maintain this calm and patient pace, and if they turn agreements into a system of thinking capable of managing not only issues, but also the mindset behind their management.

Today, relations are not measured by the number of protocols, but by the ability of the parties to read the world with open eyes. In this sense, Madrid and Rabat seem to be, in an undeclared manner, developing a ‘Mediterranean doctrine’ that restores balance in a turbulent space and rewrites the economic and political rules in a Mediterranean that is becoming increasingly heated with each crisis in the Middle East and each Atlantic tension.

Thus, the meeting in Madrid transcends the merely political; it becomes a quiet shift towards a future that can only be sustained by those who are capable of criticising themselves, reconstructing their conceptions and overcoming their historical legacy without forgetting it. In a world that is changing at the speed of light, Morocco and Spain seem to have finally decided to draft, together, a first draft of a new peace in the western Mediterranean.

Abdelhay Korret, Moroccan journalist and writer