The Canary Islands and Western Sahara: a special link

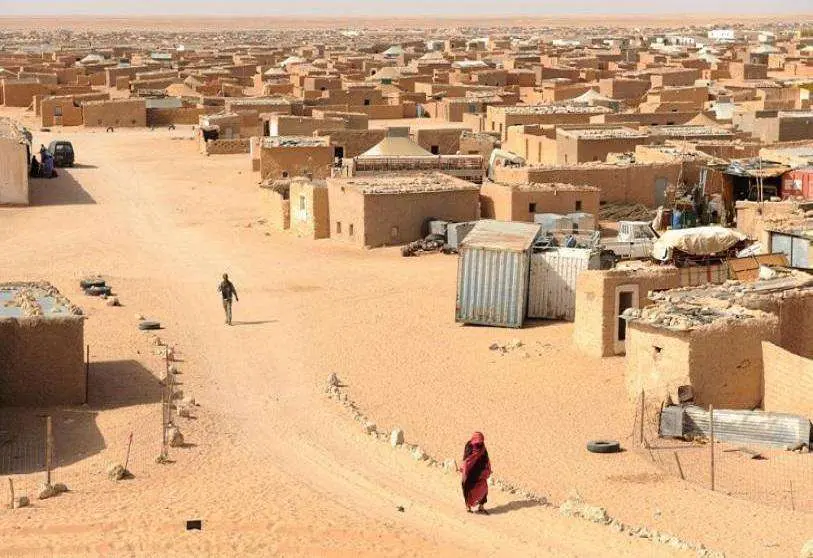

This year, Spanish-Moroccan relations will be remembered for the Spanish government's change of position on the Western Sahara conflict. In March, Madrid recognised the Moroccan position of an autonomy under Moroccan tutelage as the best solution to the conflict, thus abandoning the notion that the UN would resolve the dispute. The shift is significant, as Western Sahara remains a territory pending decolonisation, making Madrid - the former colonial power - a stakeholder in its future international status. The shift towards Moroccan theses altered Spain's relations with the Maghreb: Relations with Morocco recovered and those with Algeria worsened. Finally, Spain's image vis-à-vis the Polisario is mortally damaged, as Tindouf sees Spain's position as a betrayal of its cause.

At the national level, all parties - with the exception of the ruling Socialist Party - censured the decision. There were also reactions at the regional level. Those in the Canary Islands, perhaps the autonomous community where the pro-Saharan cause is most deeply rooted, stand out. This is why we need to know the reasons that link the Canary Islands to Western Sahara in order to understand this position.

The most obvious reason is geographical proximity, which probably means that anything that happens there is experienced more intensely than in the rest of Spain. This feeling increased after the Spanish withdrawal in 1975-76, as many Spaniards living in the Sahara settled in the Canaries, bringing, like the Algerian pieds-noirs in 1962, their longing for their lost home to the French metropolis. Even today, many Canarians still remember relatives who did business in the Sahara, and some older ones say that, when they return, the locals approach them with emotion as they recognise them for having worked or traded with them when Western Sahara was Spanish. Add to this the turbulent post-colonial history of what was once their home, and it is understandable that whatever happens there resonates more strongly in the Canaries than in the rest of Spain.

This longing has resulted in the formation of a political mentality hostile to Morocco - guilty of "occupying" the Sahara - and sympathy towards the Polisario - even though the latter was born to expel Spain from Western Sahara and attacked Spanish fishing vessels in the past - in part of Canarian society and political formations. This explains the humanitarian support given to the Saharawi camps and the politicization of noble charitable acts, such as the arrival every summer in the Canary Islands (and other parts of Spain) of Saharawi children to spend their holidays away from the refugee camps, taking them to visit public institutions. This gesture can be a laudable action, as for two months, the children in care forget about the miseries of their daily lives, without the need to take them to visit relevant places, as they are most likely unaware of why they are being taken there when they could be enjoying the Canary Islands with their host families. Paradoxically, in an autonomous community where many immigrant minors arrive and refugees from Ukraine have arrived, they have not been taken to visit such institutions.

The migration issue, whose origins go beyond the Saharawi conflict, is also used in the Canary Islands as a weapon against Morocco. The fact that Rabat uses migration as a measure of pressure in its relations with Spain leads to the association of migratory upsurges with the mood of the Alaouite kingdom, minimising other factors such as the weather or the surveillance of the coasts of the migrants' countries of origin, such as Senegal, Mauritania and Guinea. As a result, a reality is simplified that has its origins in events unrelated to Western Sahara, but which are more worrying for the security of the Canary Islands, such as instability in the Sahel, climate change or the lack of opportunities in the countries of origin of immigration.

The final aspect that makes the Canary Islands relevant to the Saharawi conflict is diplomatic representation. Both Morocco and the Polisario have a consulate and a delegation respectively in the Canary Islands. Proof of the importance Rabat attaches to promoting its image in the Canaries - where there is a large Moroccan community - is the change of consuls general. Ahmed Moussa, who held the post until last month, was replaced by Fatiha El Kamouri, who had consular duties in northern Spain. Such a gesture can be interpreted as Rabat's attempt to improve its image in an autonomous community where its rival's cause is still strong, but where Rabat has the advantage that relations with Spain are on the right track and its theses on the future of Western Sahara are increasingly accepted by the international community. A change of image, with a consul with a conciliatory profile, probably indicates that Morocco will play the moderation card in the face of what they see as Polisario's aggressiveness, thus trying to win institutional sympathy.

In conclusion, the Saharawi conflict, which this year had an impact on Spain's relations with the parties involved, had a special echo in the Canary Islands. The Canary Islands' proximity to Western Sahara, heightened by the arrival of those who lived there when it was part of Spain, is one of the reasons for the islands' attachment to the area. Such longing has given rise to sympathy for the Saharawi cause, resulting in the politicisation of humanitarian and charitable work. In the field of migration, the Saharawi cause creates a simplistic discourse on immigration, blaming Rabat for migratory surges, ignoring factors such as weather, conflict and lack of employment in the countries of origin. Finally, the diplomatic presence of both sides in the Canary Islands institutionalises the conflict, especially for Morocco. The appointment of a new consul, with a more conciliatory profile, indicates that Rabat will play the moderation card to gain more institutional support in an autonomous community where its rival has more popular support.

Alberto Suárez Sutil holds a BA in International Politics and Military History from Aberystwyth University (UK) and an MA in Security and Terrorism from the University of Kent (UK).