France undergoes a change of era with a diffused centre ground

No one is the same as before the pandemic, the most traumatic event experienced globally so far in the 21st century. It was to be expected because the same cycles of history expose it: when things get worse, there is fear; fear; uncertainty; resentment and that feeling that everything is going wrong that translates into citizen ostracism and the vote of rage that wants to destroy everything... to change it from the top down.

In 2017, France recorded a GDP of 2.3% and in 2023 it grew by 0.9% while inflation in 2017 was 1.19% and in 2023 it closed at 4.9%; and another relevant indicator: the unemployment rate in 2017 was 8.6% and in 2023 it was 7.6%.

Emmanuel Macron won the 2017 elections, defeating François Hollande and proposing with his "En Marche" party a series of centrist policies aimed at advancing social issues and boosting business activity.

Seven years have passed since then and Macronism is dead. Today, France is deeply divided with an increasingly confrontational society: economically, socially, ideologically and politically. If Macron fails to convince left-wing, communist and environmentalist parties to support him, the future of France will be in the hands of the far right.

What goes around comes around. The far-right Marine Le Pen does not hide her satisfaction at the fact that her party, Rassemblement Nationale, has her hands on the olympus of power. In an editorial, the New York Times notes that "the centre has collapsed in Macron's eyes" and anticipates that the country is heading towards ungovernability.

The first political scenario that Macron could face, following the second round of the legislative elections on Sunday 7 July, is to co-govern with a prime minister other than his party's prime minister and thus open a so-called cohabitation government. That is, Macron as president hanging on by a thread, with either a far-right or far-left prime minister and a very fragmented National Assembly in which his party would be the third or fourth force.

Macron is likely to lose his young prime minister, Gabriel Attal. France is a semi-presidential constitutional republic and executive power is shared between the president and the Prime Minister. If Macron does not manage through a pact with the new legislature to hold on to the government, he will lose his prime minister and will most likely end up cornered in a motion of censure and a general election will be called.

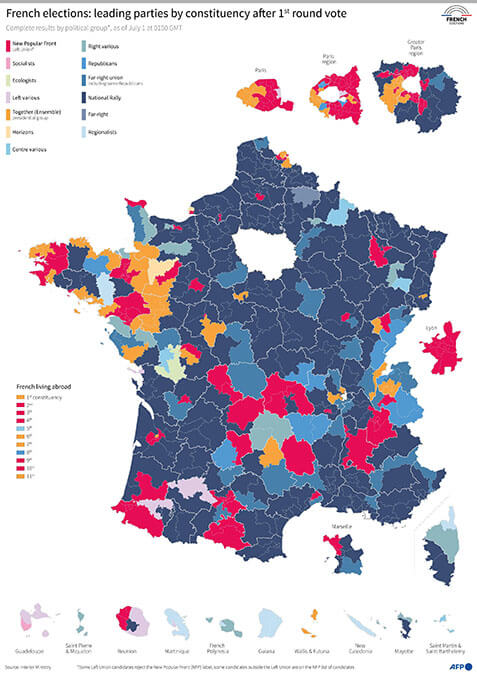

The results of the legislative elections of Sunday 30 June already showed "per se" the rupturist division in French society; how divided the positions are between an older generation that voted for the New Popular Front, which presents itself as an anti-fascist coalition, and the "millennials" who voted for Le Pen and his extreme right-wing National Rally. The twenty-something Generation Z crowd is also highly radicalised, many are followers of the ultra-leftist La France Insoumise of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a member of the New Popular Front. Mélenchon has repeatedly stated that he wants to be France's new Prime Minister.

And, although they are poles apart, history always shows that a far-right government is just as bad as an ultra-left one, because both always walk the same line: more power, more control and fewer freedoms.

The French electorate is undergoing an unhealthy pulverisation as a result of internal polarisation, sponsored by a series of acrimonious issues that have degraded coexistence and lowered the quality of life of the people living in France.

For Le Pen and his National Rally, the fault lies with the lax immigration policies that have led to a flood of immigrants who have only brought insecurity, crime and misery to France. France is for the French, argues the president of Rassemblement Nationale, Jordan Bardella, a 29-year-old millennial with good oratory skills.

In the first round of the legislative elections, Rassemblement Nationale emerged victorious with 34% of the vote, followed by the New Popular Front with 28.1% of the vote and, in third place, President Macron's "Ensemble" with 20.3%.

The stakes are crucial: from the governability of France; the paralysis in the National Assembly of the budgets and Macron's proposals (577 members of the National Assembly will be renewed): the possibility of calling early general elections and even the social fire in the streets.

The most progressive part of France is uniting to stop in its tracks the rise of the far-right that has haunted France since October 1972, when Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine's father, founded the National Front for French Unity.

The key is in the hands of the New Popular Front, a maxi alliance that recovers the name already used in France between 1936 and 1938, when it was also fighting against the spread of fascism. A political cycle that came to dominate a large part of Europe and that raised governments such as Nazism in Germany, Benito Mussolini's fascism in Italy or Francoism in Spain.

Only this New Popular Front can confront the French ultra-right, which Le Pen is so fond of, because she has personally taken it upon herself to qualify and claim that they are "a moderate right".

The same is true of Giorgia Meloni in Italy. The Prime Minister who belongs to Brothers of Italy and who repeats left and right that "there is no place in Italy for racists and anti-Semites". Le Pen and Meloni represent the local native image in which many see themselves (or would like to see themselves) reflected: blonde, white, good-looking and with coloured eyes.

Who can stop the aspirations of the "Le Penists"? Undoubtedly, the New Popular Front, which is made up of left-wing parties (of all spectrums) starting with the ultra-left of La France Insoumise; in addition, the Socialist Party with social-democratic overtones has joined them; also the French Communist Party and the Greens of the Ecologistes party have been added.

This is not the first time they have carried out a pact of convenience: they did it in 2022 when Macron ran for another five-year term. In those elections, this pact won 131 MPs, and they were partly responsible for preventing the absolute majority that Macron won during his first election victory in 2017 when he defeated François Hollande.

UK as a gateway to the European club fan

Mujtaba Rahman, head of European politics at Eurasia Group, reflects on the idea that if the French electorate wants something new, as it usually does, Le Pen will be its only real option.

In these legislative elections, Rassemblement Nationale will also grow as a legislative force from 88 MPs in the National Assembly to possibly double that number.

Nor does Mélenchon's constant accusations against Le Pen, her family and her party seem to do him much harm. The ultra-left leader insists that Marine is a wolf in sheep's clothing, an "authoritarian and xenophobe"; that her family rubbed shoulders with the Nazis and was a collaborator with the Vichy regime (1940 to 1944); and points out that her party, Rassemblement Nationale, is very close to the Kremlin and even hints that the Kremlin may have given her some financial contribution.

Le Pen is a supporter of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin and has on more than one occasion declared that she will not send arms to Ukraine and will do everything possible to end the war as soon as possible.

In this regard, Rahman wrote in Politico that, if Le Pen were to be elected president, she would at best lead France into five years of drift and turmoil, both internally and in its relationship with the EU.

"At worst, she could pull France out of the Western alliance, initiating a process that could split the EU, at least in its current form," he remarks.

There are many things in the pipeline, in economic policy; in migration policy; in social policy; in LGBTI rights; in the position of the French state with regard to various progressive values and in France's international position towards its support for Putin; its intervention in the invasion of Ukraine; the same with regard to Hamas and Israel and its position in international organisations such as NATO, G7 and the EU. Le Pen is a nationalist and does not accept interference from the EU.

Will Mélenchon be Prime Minister?

The other polarisation is raging on the French streets. In Paris, the anti-fascist marches mobilised by Jean-Luc Mélenchon of La France Insoumise are getting bigger every day. "It's them or us," declared the veteran politician, who will be 73 years old.

However, the other left-wing, communist and environmentalist parties with which he is allied in the National Front do not want him as prime minister. A situation that will make for difficult negotiations for the new government.

The paths between the two sides are bad for Macron: if it is Le Pen's far-right that wins a significant percentage of legislators in the National Assembly, Macron will have to accept the far-right Jordan Bardella as prime minister. Not only will he be even younger than Attal, but he will also impose his anti-immigration agenda on the Elysée.

Already, National Rally has been announcing that it will limit access to key positions in various areas of government and within the public sector to French nationals born in France.

And if it is the ultra-leftist, Mélenchon who turns out to be the new prime minister, it is also bad for Macron. Among the radical left's proposals are a reform of the electoral system for greater proportionality, a rise in the minimum wage, a new tax on large fortunes, free school materials and meals, as well as retirement at the age of 60.

Furthermore, in international politics, they call for recognition of the State of Palestine; an arms embargo on Israel; and, with regard to the war in Ukraine, France Insoumise is committed to continuing to send military aid, but without France intervening directly in the conflict. Their ideas are equally nationalist and Eurosceptic.

The analyst Marc Bassets wrote in El País that France, the cradle of an idea of a Europe of human rights and the Enlightenment, has to decide whether to put the Eurosceptic and nationalist far right in power or to confront its unstoppable rise with a heterogeneous coalition ranging from the radical left to the moderate right. A "Frankenstein" coalition.

Of course, for Macron and his centrist policies, the cost will be enormous. Right now, the ball of power is being fought over in a dogfight between the "lepenist" ultra-right and the ultra-left of Mélenchon. And this is certainly not good news for France's immediate future.