The post-pandemic Algerian Hirak: is the entry of radical Islamism still a possibility?

Four months after the second anniversary of the Algerian Hirak and its resurgence after being banned in March 2020 due to the global pandemic, the social and peaceful mobilisations that sustain it continue. Meanwhile, in the shadows, radical Islamism is represented by Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and, even further afield, Daesh. Until today, both organisations have kept a low profile with regard to the mobilisations, but it cannot be ruled out that they will take advantage of any hint of social weakness to capitalise on Hirak.

The 10 February 2019, when Algeria's former 20-year president Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced his candidacy for a fifth term in office, marked the precipitating factor in the wave of social mobilisations that continues to this day in the country.

The so-called Hirak has acquired and maintained throughout its history, on the one hand, a transversal and intergenerational character. These are social marches that transcend gender, generation and ideology. However, despite its heterogeneity, it is a unique movement involving different sectors of society fighting peacefully for the same cause: independence from the authoritarian regime, which, disguised as democracy, has remained intact since the end of Algeria's black decade1.

On the other hand, the pacifist spirit of these social marches brings with it an apolitical character and a rejection of international intervention, as well as an intransigence towards the jihadist message that they strongly reject, fearing that it could distort the nature of the Algerian Hirak2.

Algeria's history is marked by experiences that provided a fertile stage for the emergence of Salafist discourse. This situation is evidence of a collision between social lessons learned that repel a return to the mistakes of the past and the permanence of a jihadist past in Algeria, which, as the historical territory of the AQIM3 organisation, is keen to recover its presence in the region.

In March 2020, the pandemic led to a ban on mass gatherings, with the result that Hirak was hampered for a period of nearly a year. Until then, the social marches achieved some isolated successes, such as Bouteflika's resignation, keeping international and Islamist actors on the sidelines, and the arrest of important regime figures. However, Tebboune's arrival in government with a high abstention rate was a major legitimacy deficit given that the presidential candidates and the current president were even part of Bouteflika's government.

This change of government was presented to the public as open to transformation. However, despite making small changes, these have been aimed at mitigating protests. In short, this governmental transition entails the reorganisation of the political façade, with a democratic appearance, but the essential structure of the regime has been maintained with power in the hands of the army, the secret services and the upper echelons of the government. An internal configuration that resembles the old regime that has dominated the country since Algeria's independence in 1962 through corrupt and inconsistent socio-political and economic management4.

Today, the Hirak, despite its great strengths, is being closely followed by a number of obstacles. The structural disorganisation resulting from their non-partisan nature prevents them from becoming a strong and organised opposition to power, leaving this popular uprising in a state of stagnation. Moreover, since the pandemic, the authorities have been imprisoning leading Hirak figures following a clear roadmap: to take advantage of the health crisis to repressively prevent the resumption of protests. Nevertheless, Hirak has continued to stay afloat mainly through social media; an element that has accompanied the peaceful protests since their inception and after a pause of almost a year, the mobilisations have resumed again.

On 12 June 2021, Algeria's legislative elections, originally scheduled for 2022, were held. These were marked by government repression and boycotts by the Hirak, once again with a high abstention rate of around 70%. These elections were intended to dissipate the Hirak movement by giving momentum to Tebboune's 5 "new Algeria". However, according to analysts, the main beneficiaries of these elections were the Islamist parties: first, the Movement for a Society in Peace (MSP), which is very close to the Muslim Brotherhood, and second, the El Bina Movement6. "Islamism is not dead in Algeria"7.

There is no doubt that, given the continuity that this movement has shown over the past two years, it is not an ephemeral phenomenon and, moreover, it does not conform to simplistic changes. Nevertheless, Algerian power is challenging the Hirak through attrition with a trend of increasing repression against the citizenry. Contiguously, but as an independent bloc, the terrorist organisation AQIM has not retreated from the road. It is waiting for a certain fraction of the protests, through accumulated frustration and weakening, to compromise on the Salafist message. The aim of its strategic campaign is to capture the attention of the younger generation by offering them a final alternative.

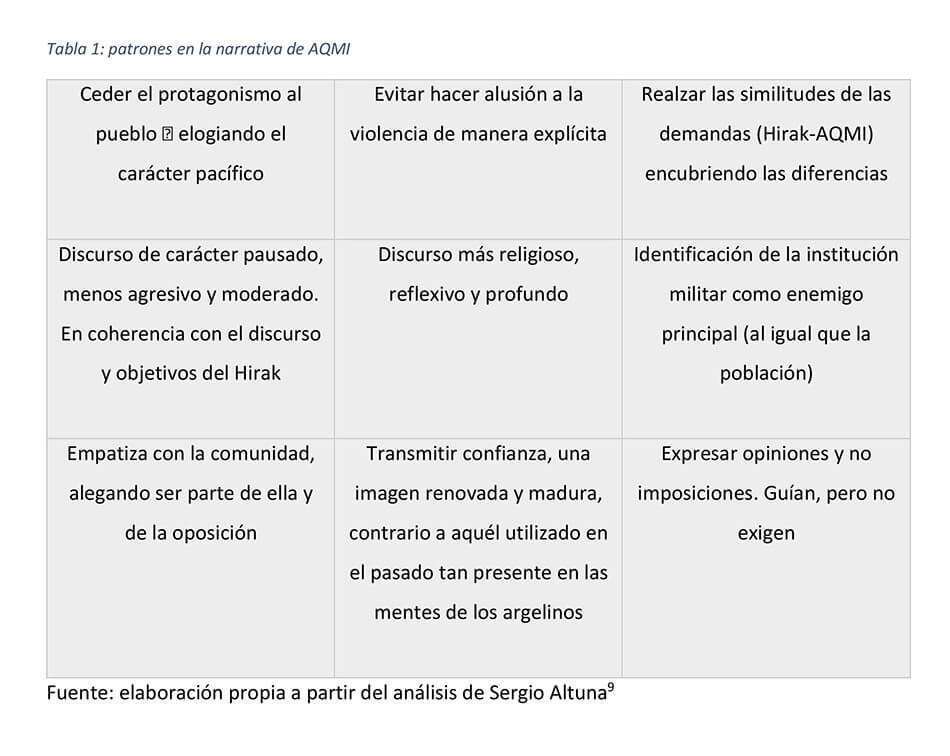

The role of Islamic fundamentalism in the Hirak led by AQIM, following Sergio Altuna's analysis of its discourse in the organisation's own texts, has, since the beginning of the protests, taken on a slow, moderate character, in line with the civil message. It is a discursive strategy that aims to transmit confidence and reconfigure itself into a new, renewed image that empathises with the Algerian community. The organisation8 has tried to interpret the situation by seeking an asymmetry between its discourse and that of civil society, to which it has ceded all the protagonism in its arguments. In this way, it has sought to carve out a niche for itself in the revolt when the most unstable period arrives in the region.

The strategy has therefore been based on remaining on the sidelines but offering a covert alternative in close proximity to which the younger population can be attracted. This has been externalised through a message with certain patterns that connect with the Hirak message, which we can unify as follows:

AQIM praises the pacifist character of the protests, but just because they do not explicitly integrate the use of violence in their presentation discourse does not mean that they have divested themselves of the recourse to action that represents them. When the time comes, the people will be able to take this route according to the interpretation of jihad that jihadist terrorism upholds: the right and obligation of every Muslim to take refuge in the narrative of defensive jihad in the absence of any other alternative, exercising violence for the sole purpose of protecting the territory.

However much its discourse has evolved, it is a strategy of externalisation, so it should not be forgotten that behind this temporarily acquired external cloak, it is only a strategy to attract attention. Al-Qaeda is a grassroots militarist organisation, however much it tries to camouflage its character in its discourse. Such a discourse is simply a method of empathising with the younger Hiraqis.

At the moment, the Hirak remains united and steadfast to its peaceful nature but government obstacles and time are working against it. The Hirak is currently in a fragile state and is in danger of splitting given the repression and smear campaign the government has been waging. Moreover, the fact that Islamism has benefited from the recent elections opens the way for part of the population to be susceptible to the Salafist message.

Journalist Arezki Metref writes in the daily El País: "The persistence of Hirak, despite the repression and the pandemic, represents a real problem for the authorities. The movement has nerve, it is not a one-day flower. And that's why the powers-that-be are stoking divisions".

Will AQIM's jihadist past in Algeria finally act as an inhibiting factor or a predisposing factor?

- Amirah-Fernández. H (2019): Round table "Algeria in transformation: Mobilisations for change and political uncertainty". Real Instituto Elcano. 25/04/2019:

- http://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/wps/portal/rielcano_es/actividad?WCM_GLOBAL_CONTEXT=/elcano/elcano_es/calendario/actividades/mesa-redonda-argelia-en-transformacion-movilizaciones-cambio-incertidumbre

- Redacción. (18 de febrero de 2020). En Algérie, les réseaux sociaux, garants de la mémoire d'une contestation inédite. Slate Afrique. Recuperado de: http://www.slateafrique.com/

- Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Al Qaeda affiliate created in Algeria in 2007, inherited from the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) and present in many countries in the Maghreb and Sahel regions.

- Redacción (25 de septiembre de 2019). The end of the empire of the most mysterious man in Algeria. La Vanguardia. Retrieved from https://www.lavanguardia.com/

- Redondo, R. (2021) High abstention and disinterest mark legislative elections in Algeria. Atalayar. Retrieved from: https://atalayar.com/content/la-alta-abstenci%C3%B3n-y-el-desinter%C3%A9s-marcan-las-elecciones-legislativas-en-argelia

- Messara, M/ EFE. Repression marks Saturday's parliamentary elections in Algeria. La Razón. Retreived from: https://www.larazon.es/internacional/20210611/6h7bnpipgfhevmswoj4q6ngjta.html

- Ghanem. D (2019): Mesa redonda “Argelia en transformación: Movilizaciones por el cambio e incertidumbre política”. Real Instituto Elcano. 25/4/2019

- Altuna, S. (2020). AQIM versus Hirak: modulation of discourse while awaiting a window of opportunity in Algeria. Real Instituto Elcano ARI 23/2020

- Altuna, S. (2020). AQIM versus Hirak: modulation of discourse while awaiting a window of opportunity in Algeria. Real Instituto Elcano ARI 23/2020

Gorane Mendieta Díaz, criminologist specialising in the prevention and analysis of terrorism and Sec2Crime collaborator https://www.sec2crime.com/