Algeria and South Africa are held back by syndromes

Crises, not solutions, are what the Algerian president and his officers seek.

Two particular African countries stand out by continuing to dwell on issues of colonialism and racism while the world is rapidly building foundations for advancement while keeping pace with major changes taking place.

An unhinged political compass has led such countries as Algeria and South Africa to stray off the course of progress despite the abundance of natural and human resources at their disposal.

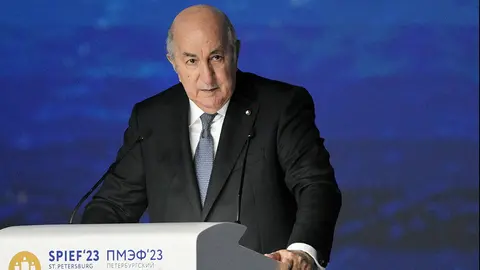

The return of South Africa’s ambassador to the United States, Ebrahim Rasool, to his home-country after Washington declared him persona non grata, oddly coincided with Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune’s annual meeting with domestic media, where he again revisited his anti-colonialist narratives.

The frequent mention by the Algerian leader of colonialism and his country’s thorny relationship with France while the South Africans dwelt on racial issues made such a coincidence bound to happen often.

Ambassador Rasool returned without any regrets, he said, despite taking a diplomatically contentious stance by any standards. Ambassadors are usually dismissed after political clashes between their own country and their host nation. No personal considerations are usually involved. But Ambassador Rasool changed the norm and his personal attitude led to the diplomatic frictions.

Of course, no one is saying that US President Donald Trump, whom Rasool despised and called “racist,” is an angel. Much has been said about Trump, but diplomats usually keep their misgivings to themselves and do not express them imprudently. Trump was not back in office for too long before providing his critics with sufficient ammunition to hate him and consider him racist. However, the difficult interaction between a racially “complex-ridden” country like South Africa and a country which is open to everything like the United States, made it possible for disagreements to emerge. But no one expected such disagreements to reach the level of expelling an ambassador for “racism”-related reasons at a particularly inopportune time.

The racism that a country like South Africa is invoking as a justification for this usually uncommon diplomatic incident, with the expulsion of its ambassador, is one created by South African politicians and foreign ministry officials.

Moreover, it is an atmosphere fuelled by public mood, making it part of the “popular culture” that South Africa has inherited from the truly racist Apartheid era. However, the founders of modern South Africa, both the black freedom fighter Nelson Mandela and his white deputy, Frederik de Klerk (the former president who stepped down to make way for the post-apartheid era), never intended for the state to be rebuilt based on a racial syndrome permeating all matters large and small.

In an atmosphere poisoned by racist rhetoric, it is possible that tens of thousands of white South Africans of European descent will consider emigrating to the United States. This would constitute a huge loss of human resources and know-how for any country. This is all the more true for South Africa because the white minority there has been, until recently, a pillar of the national economy and a significant driving force behind South Africa’s achievements. The Mandela-De Klerk equation was a recipe for survival, not for exodus or expulsion. It was meant to pave the way for whites of European descent to remain in their country and complete the complex history where the wise Mandela was able to write a bright chapter overcoming the racist past.

What makes the expulsion of Ambassador Rasool and the desire of tens of thousands of whites to emigrate to the United States such a sensitive issue is that both developments are likely to be a prelude to another stage dictated by racial issues.

South Africa is a melting pot of many ethnic groups, encompassing Ibrahim Rasool’s ethnic background. He is a Muslim of English, Indonesian, Dutch, and Indian descent. Many South Africans can trace their ethnic origin back to multiple ancestors. However, blacks remain the majority in terms of numbers, which could be very problematic if this majority turns against its current partners in government, both as individuals and as ethnic groups of non-white origin, or if they rescind post-apartheid laws.

In such a toxic atmosphere, racial accusations swirl in all directions.

In the meanwhile, President Tebboune finds the time to invoke the French colonialist era in his country, which suffers from a host of problems of another kind. The Algeria about which Tebboune constantly talks in his speeches and political events is one that he depicts as a victim of French colonialism, not a nation that has been able to transcend is past legacy and take the necessary steps towards political and economic rebirth. Other countries, including those on the northern shore of the Mediterranean and those south of the Sahel and the Sahara, have managed to do so. The French colonial era in Algeria is systematically invoked to ensure that the political atmosphere between France and Algeria remains toxic and engenders more crises fuelling escalation and dire warnings.

For some reason, Algeria has prompted a number of crises in its relations with more than one country. President Tebboune seems to consider that his mission as president requires diplomatic escalation with his country’s economic and political partners in Europe and Africa. Since his rise to power, following a crisis over the rule of his predecessor, an ailing and disabled president, diplomatic crises have raged between his country and other partners. There was no reason nor explanation for this except maybe the need felt to provoke preemptive tensions over anything that might affect the relationship or the position of any one country regards the Polisario Front. It remains difficult to understand, even by the complicated diplomatic considerations of a country like Algeria, why, for example, this North African country would choose to clash with an entire geographical bloc in the Sahel region, or why a sovereign political or diplomatic decision by Spain to recognise Moroccan sovereignty over the Sahara region, would turn into a crisis undermining Algeria’s own economic interests.

This attempted guardianship by Algeria over the Sahara issue raises many questions because it is inconsistent with Algerian national interests. Observers find that justifications to be diminishing as everything trickles down to issues of personal interest motivating a group of army officers who benefit from the crisis, which has been ongoing since the 1970s. Crises are what the Algerian president and his officers seek, not solutions.

Tebboune says he has entrusted the task of resolving the issues with France to the capable hands of Foreign Minister Ahmed Attaf, while assigning the task of handling these issues to both himself and French President Emmanuel Macron, whom he designated as “the sole reference” for his country.

The president has drawn up a preliminary plan to cope with the escalating crisis, excluding and included whom he wanted arbitrarily while assigning the matter to his foreign minister and entrusting the rest to Macron.

This is rather confusing because it is the same Macron who has caused the crisis and brought it to its current stage. If Tebboune keeps on looking at everything through his narrow prism, the crisis will undoubtedly appear intractable. Adding to the traditional confusion created by talk about the colonial legacy, it will be difficult to ever find a solution. There may be a need for more seasoned Algerian diplomats than Ahmed Attaf and for French politicians who are less right-wing and more cognisant of what has become known as the “Algerian syndrome” regarding colonialism and the inability to overcome past legacies.

A more effective option that could be to wait for a new presidential term in France where the new president would acknowledge, in his inaugural address, the abuses perpetrated by France in Algeria. If one has learned one lesson from Algeria’s post-independence history, it is that none of this will ever happen. Algeria will likely return to square one, and will not break free from the cycle of accusations and counter-accusations.

This type of insularity on the level of ideas, no matter how just and legitimate they might seem, makes it difficult for South Africa or Algeria to move far in improving the lives of their peoples. Both will remain mired in political and diplomatic stagnation. Nations achieve progress only when they overcome their syndromes. They cannot continue putting on trial, at every step of the way, the racist mindsets that ran a country like South Africa, nor blame the mentality of the colonial-era generals who undoubtedly committed shameful and grave transgressions, as was the case in Algeria.

Soon, the demographic majority in South Africa will be that of people born after the end of the apartheid era. I am not sure what percentage of Algerians remember the French soldiers who roamed the neighbourhoods of Algerian cities, towns, and villages. But it is more than ever imperative to break free from the syndromes inherited from the past. These cannot constitute the compass which guides relations between nations.

Haitham El Zobaidi is the Executive Editor of Al Arab Publishing House.