Desmond Tutu

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, leader of the 1.5 million Anglicans in the country (80% black) and whose influence over the years has extended far beyond that limited local parishioners, has just passed away in South Africa at the age of 90. An indefatigable fighter against the Apartheid regime, he defined himself as a "man of peace and not a pacifist" because although he preached with Mandela a non-violent response, he understood that it was not the blacks but the white oppressors who had brought violence to the country and that is why, when years later he chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he was against a general amnesty for the crimes of apartheid and demanded reparations for the black victims of the abuses of the white minority government.

He believed that apartheid dehumanized both the oppressors and the oppressed and wrote a book significantly entitled "No future without forgiveness". His struggle against racial segregation led him to harshly criticize Ronald Reagan's policy of "constructive engagement" which sought to follow a line of impartiality and to consider apartheid as an internal South African problem, as he rightly understood that to be impartial in the face of that injustice was in fact to take sides with those who inflicted it and against those who suffered it. In 1984 he received the Nobel Peace Prize for his constant struggle for equality between blacks and whites. And no doubt for the same reason in 2010 he tried unsuccessfully to stop the Cape Town Opera Company from performing in Israel, comparing Israeli policy towards the Palestinians to what blacks had suffered years earlier at the hands of whites in his own country.

He was born into a humble Methodist family that converted to Anglicanism and from childhood he was aware of the subordinate situation in which his race placed him. He recounted how his father suffered when a white man called him "boy" (something like a servant) in front of his son and how he was shocked when another white man respectfully greeted his mother by touching the brim of his hat. It turned out to be Bishop Trevor Huddlestone, a determined anti-apartheid campaigner. Following his example, Tutu left a teaching career to go to London to do a master's degree in theology at King's College. I was fortunate to meet both of them. Huddlestone when I attended an anti-apartheid conference in London and Tutu years later in Cape Town when black apartheid was still in force. I was then Director General for African Affairs at the Foreign Office and he was kind enough to receive me in his home.

I remember him as a man of small stature, very smiling, with an enviable sense of humor and sitting in front of a huge rectangular fish tank with fish that he himself took care to feed. He would say things like "before we had the land and they had the Bible and they told us to pray by closing our eyes and then, when we opened them, they had the land and they had left us the Bible". He gave every impression of a friendly, good-natured grandfather who didn't seem like the tireless, fearless fighter he undoubtedly was. I left his house impressed with the character and thinking that one should never be carried away by appearances.

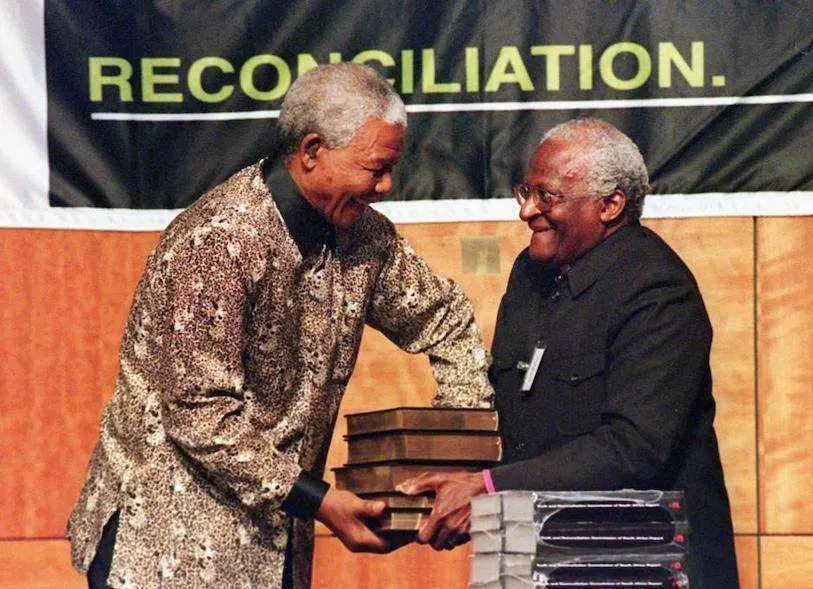

His relationship with Mandela was very good and he constantly encouraged him to get things right because he said they could not afford to fail the people after all the effort and suffering invested in ending apartheid. That is why he unreservedly praised Frederick De Klerk when he dismantled it and was very critical of the African National Congress leaders who succeeded Mandela in the presidency of the South African Republic, Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma, for their corruption and for betraying the ideals that had animated his struggle, going so far as to say in an interview that "our government is worse than apartheid".

When De Klerk announced his end, the news caught everyone off guard. As luck would have it, that same day in 1989 I was in Kampala, the capital of Zambia, with Mbeki and the ANC leadership, which was then in exile, when someone interrupted the meeting, reporting the president's speech, and everyone left in a stampede to travel to South Africa. The meeting ended there and then amidst an atmosphere in which I do not know whether surprise or joy prevailed. Probably both, and also concern and a sense of responsibility for what was coming to the ANC as the party presumably called upon to form the government. It was one of those rare times when I had the strong feeling of watching history unfold before my very eyes.

He leaves behind a wife to whom he had been married for 66 years, four children and several grandchildren. He was an admirable man, one of those who contribute to leaving the world better than how they received it, of which there are not many. May he rest in peace.

Jorge Dezcallar. Ambassador of Spain