Decadence and its end

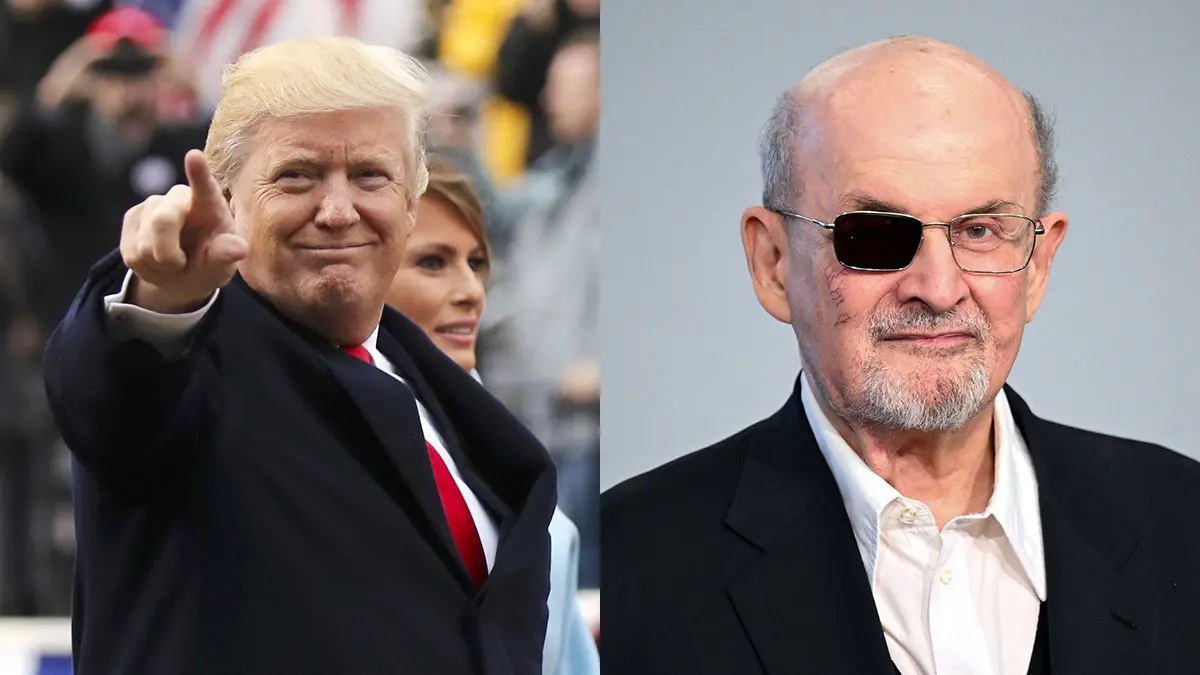

A real estate speculator of Indian origin, lout and millionaire lived the death throes of his triumph in an artificial America, where any success, trend or identity made sense as long as it was dressed in superficiality. Were it not for the fact that the two public figures have been the victims of respective attacks perpetrated by exalted and unknown citizens, it would be difficult to find any parallels between the Indian writer, an atheist with Muslim roots, who was condemned to death by the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 for having satirised Islam in ‘The Satanic Verses’, and the populist tycoon who reached the White House with a provocative speech.

Some relevant historians, Professor Manuel Morán among them, consider the 1979 Iranian revolution to be a historical milestone in the synchrony of the last third of the 20th century. At the time, it led to the breakdown of the bipolar order in the Middle East and the Muslim world, the Soviet Union's intervention in Afghanistan in anticipation of a hypothetical US action in Afghan territory, and the reconfiguration of alliances between Sunni and Shia minorities and leaders.

The Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, the subsequent invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussein and the attacks on the Twin Towers can be traced back to the Iranian revolution. And so, therefore, can the invasion of Iraq and the Syrian war. And, consequently, so can the attacks and the war in Gaza and the explosives camouflaged in mobile devices used against Hezbollah guerrilla activists.

Geopolitical and oil interests, terrorist actions and the clash between minorities fuelled by different centres of power and numerous satrapies have been the cause of so much violence. Not the words written by a successful novelist, made a victim by a fatwa of Imam Khomeini and subsequently turned into a celebrity by various ultra-progressive sectors, who demonise Israel with the same intensity as the successors of the fundamentalist leader of the Iranian revolution.

This contradiction is not reflected in Salman Rushdie's latest publication, ‘Knife’, in which the writer, now one-eyed and still bewildered, summarises the dramatic moments he lived through when in 2022 a stranger stabbed him several times in a contest in Chautauqua (NY) to fulfil the mortal destiny announced in the last third of the 20th century, and which history had reserved for him at the dawn of the third decade of the 21st. But his account, humane, sincere and inspiring, denotes a conscious and resigned feeling for the consequences of decadence in an artificial society like the one he anticipated in his 2017 novel.

Donald Trump and Salman Rushdie are two characters who do not coincide in any way, beyond having been born at the same time, 1946 and 1947, having become two celebrities and having suffered irrational attacks originated by a similar ‘leitmotif’: the intolerance propagated relentlessly in the perverse sphere of networks and memes that reach and pervert reason and promote political violence and unreason.

Decadentism and individualistic, magnicidal violence were the hallmarks of anarchism in the 19th century. But the turmoil and violence did not stop with the bombings of unknown anarchist dynamiters, but crossed the borders of the First World War and multiplied in the propaganda of the communist and National Socialist mass parties in the third decade of the 20th century.

The Economist this week publishes an extensive report on the weakening of ‘woke’ thinking in US public opinion, the press, business and academia over the past three years. And as a consequence of this decline in ‘wokist’ language (white privilege, systemic discrimination, social deconstruction...), ‘anti-wokist’ terminology has also been reduced in the papers and speeches analysed by the weekly. If the trend is confirmed and the decline of extremism is credible, the regrettable attacks on a candidate for the presidency of the world's leading democracy and a famous and controversial writer could be interpreted as the end of an exhausted era. But if this is not the case, as it seems in Germany's local elections and in Venezuela, the 21st century will remain one-eyed and intolerant.