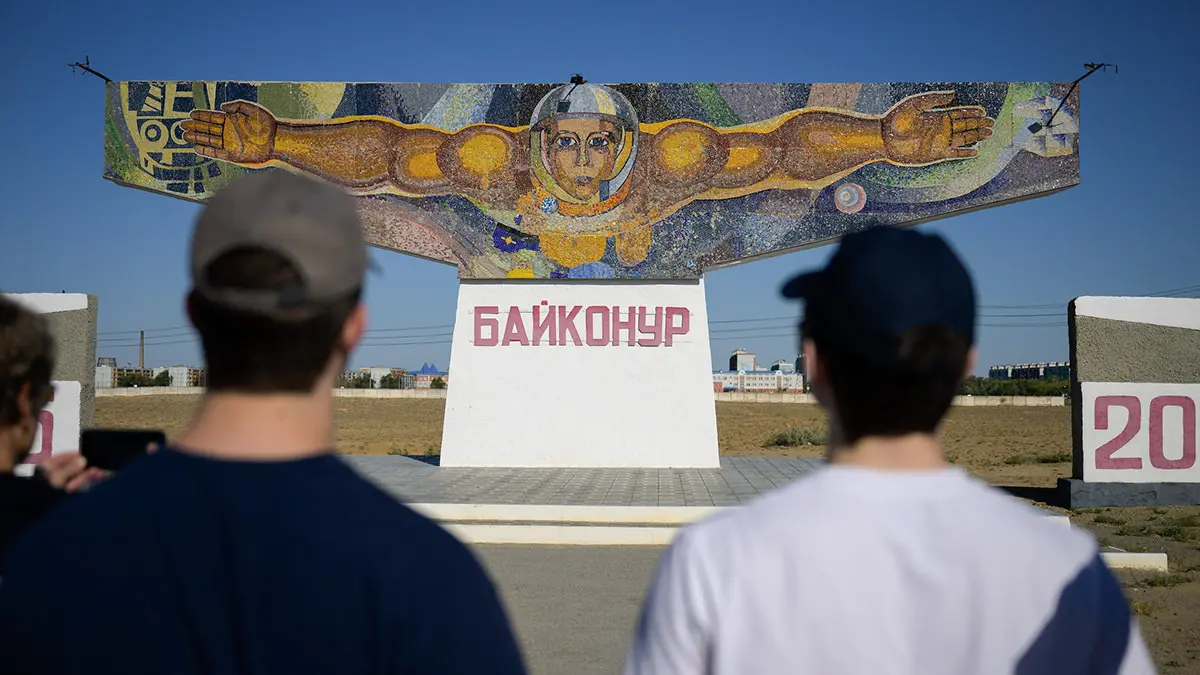

Baikonur, the place in the middle of nowhere where the space age began 70 years ago

In mid-October 2003, I had the opportunity to visit the Baikonur complex for several days. This was thanks to an official invitation from the Russian Federal Space Agency – then called Rosaviakosmos – extended by the European Space Agency (ESA) to witness the launch of the Soyuz capsule carrying Spanish astronaut Pedro Duque to the International Space Station (ISS), together with American Michael Foale and Russian Alexander Kaleri.

The Russian authorities showed me the main facilities and allowed me to accompany the Soyuz rocket from the building where it had been assembled to its launch pad. They also showed me the museum and took me to the gigantic, rusty and abandoned flight platform of the super-heavy Energia rocket, which in November 1988 put the ill-fated Soviet space shuttle Buran into orbit, a pharaonic project from the 1970s and 1980s that came to nothing.

From what I could see, the cosmodrome of 22 years ago looked more like a huge scrap yard than a space base. I didn't get a chance to see the condition of the intercontinental ballistic missile silos, but I did see camels roaming free and several of the 13 space rocket launch pads, some of which were out of service, with their metal structures rusted and the adjacent facilities abandoned. Exposed to extreme weather in summer and winter, the passing of the years without proper maintenance had taken its toll. But make no mistake.

The operational facilities I visited were spotless, and the engineers and technicians I spoke to were highly skilled professionals, proud to be pioneers and guardians of access to outer space. They were aware of the great responsibility they had and were committed to ensuring that every launch from Baikonur worked with pinpoint precision, as was the case with Pedro Duque's Soyuz TMA-3 mission. I know that the infrastructure and equipment at Baikonur have been modernised over the last 15 years.

From the Soviet Union to Kazakhstan

In 2003, Vladimir Putin had been in power for three years, replacing Russia's first president, Boris Yeltsin. Corrupt measures to liberalise the centralised Soviet economy and move towards a market economy had plunged the country into a deep crisis in all areas. The space sector was going through a period of resource shortages and decline, which engineer Yuri Koptev, the director general of the Space Agency at the time, was struggling to turn around.

The Russian authorities have just commemorated the 70th anniversary of the creation of Baikonur and, although it is not the original name of the place, it is its current name, with which it will go down in the history of humanity. Born on 2 June 1955 as Scientific and Research Test Site No. 5, it has the great merit of being the first gateway that opened the way to orbit the Earth and offer the possibility of exploring the afterlife from outer space itself.

Officially known throughout the world as the Baikonur Cosmodrome, since the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991 it has been located in the Republic of Kazakhstan. A Central Asian country, Kazakhstan is five times larger than Spain but has only 20 million inhabitants, compared to our nation's 49 million, which gives an idea of its very low population density.

Baikonur is not only the first space base to be built but also the largest in the world. Under the responsibility of the Russian Ministry of Defence, it covers an area of 6,717 square kilometres and, to give an idea of its enormous size, it is larger than the entire province of Alicante, which has 5,817 km². It is similar in size to the province of Segovia, which has 6,921 km², and 1,000 square kilometres smaller than the province of Barcelona.

A strategic enclave of the first order, President Boris Yeltsin and the President of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, signed a series of political, military and economic cooperation agreements at the end of March 1994. One of these was a lease agreement for Baikonur worth $115 million, which transferred to Russia the management responsibilities and rights of occupation, use and exploitation of the cosmodrome. Moscow wanted it to be for 99 years, but it was agreed for an initial period of 20 years, which has since been extended to 2050.

The scene of the first milestones of the space age

Baikonur was the hub of the Soviet space programme during its heyday, which coincided with the terms of Nikita Khrushchev (1953-1964) and Leonid Brezhnev (1964-1982) as general secretaries of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and visible heads of Moscow's power. The location was chosen by the Russian military for its proximity to the equator, low population density and unobstructed horizon in all four directions.

The cosmodrome was built to serve as a launch base for SS-6 Sapwood intercontinental ballistic missiles, the first test launch of which took place in May 1957, two years after construction began. Shortly afterwards, it was the scene of the first major milestones of the dawning space age: on 4 October, a variant of the same missile placed Sputnik-1, the first artificial satellite, into orbit.

From Baikonur, the first human to travel into space, Yuri Gagarin, orbited the Earth in a spacecraft on 12 April 1961. He was followed by Valentina Tereshkova, who on 16 June 1963 became the first female cosmonaut. In total, as Vladimir Putin said in his congratulatory message on the 70th anniversary, Baikonur has witnessed ‘more than 2,500 launches and sent more than 200 cosmonauts from many countries into Earth orbit, many of them scientists conducting innovative experiments and promoting fundamental and applied research on the ISS’.

The heart of Russia's now diminished space effort, the cosmodrome remains the main launch site for Russian and allied civilian and military satellites. For almost 10 years, from the retirement of the last American space shuttle (Atlantis) in July 2011 to the first manned mission of SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket on 15 November 2020, Russian Soyuz rockets and capsules launched from Baikonur were the only way for humans to reach the ISS and relieve their colleagues on board.

But Baikonur is not Moscow's only space base. It has two others. One is the Plesetsk military complex, about 800 kilometres north of Moscow. The other is the new Vostochny cosmodrome in the Far East, more than 5,500 kilometres from the Russian capital. However, neither of these two, only Baikonur, has the capacity to carry out manned space flights. Vladimir Putin has already issued a directive for Vostochny to house a new complex for sending humans into space, but this will not become a reality until the next decade.