France has not said its last word: Cohabitation, the last bomb to be defused

For the first time in 20 years, the Prime Minister could belong to a different party from the President, known as cohabitation. The duel will be decided in the pending legislative elections.

Following Macron's victory in the second round of the presidential election, his main rivals in votes, Le Pen and Mélenchon, have made statements with an unmistakable "it's not over yet" tone. On paper, it is. After the presidential elections come the legislative elections, which in the last 20 years have been practically a formality for victorious presidents. This time, however, there is reason to think otherwise. Or at least that is what France's recent history suggests.

Duality of power: why is it created and how is it managed?

The French political regime, known as the Fifth Republic, was founded in the late 1950s, its main architect being General Charles de Gaulle. It was a response to the political cataclysm of the French defeat in the Algerian War, which brought the colony to independence and brought the metropolis to the brink of civil war. The response of de Gaulle, a former Resistance hero retired from politics and called back into politics to stabilise the country, was a new constitution. In it, he created for himself and his successors a very powerful Presidency of the Republic, justifying it on the grounds that he needed the capacity to manoeuvre to fulfil the task.

The new President not only governed with an extremely strong Executive, but also with a 7-year mandate. Surely aware of what it meant to be in power for a long time, de Gaulle decided to provide himself with an assistant of sorts. Someone who could act as head of the bureaucracy, organise inter-ministerial coordination and, in short, take care of the many small day-to-day tasks involved in running a government. A Prime Minister, chosen by the President, but to be ratified by Parliament.

This last detail is of great importance. The Elysée was self-imposed to cede some influence to the party structure that supported it, as well as to its possible parliamentary allies should it need them. At the same time, it made it possible to face legislative elections that took place every five years, and therefore did not coincide with the presidential elections, sending a message of fear of instability: to guarantee the governability of the country through a fluid relationship between the Elysée and the Matignon, it was not enough to vote for de Gaulle. It was also necessary to vote for Gaullist legislators.

This scheme worked for the general, and even for his first successors. After all, electoral systems are decisive in shaping party systems, Duverger dixit. But it would not last forever. From 1986 onwards, the Socialists and the heirs of Gaullism found that a president in office could indeed lose the legislative elections. So-called cohabitation governments came into being: The President would appoint the Prime Minister who had the parliamentary majority, even if he did not belong to his party, and the two would spend a few years having a political arm wrestle.

In 2001 the two major parties, socialist and conservative, decided to reach a pact to put an end to this situation: The presidential mandate would be shortened from 7 to 5 years. This allowed both presidential and legislative elections to be held in the same year. The idea was that a newly elected president would be able to shape a parliament with his party's candidates with his own halo of victory. In this way, the Elysée could pursue its legislative agenda and keep the Matignon in its role as second-in-command, without fear of it becoming the seat of a counter-power. A Winner-takes-all scheme in the purest Anglo-Saxon style, which paradoxically was intended to put an end to situations like the American one, where a President can find himself in a minority in Congress.

The reform paid off and there have been no more cohabitations. Once again, Duverger's law in full swing. At least, until today. Because that seems to be the declared aim of the opposition(s).

Cohabitation, again plausible: attrition and polls.

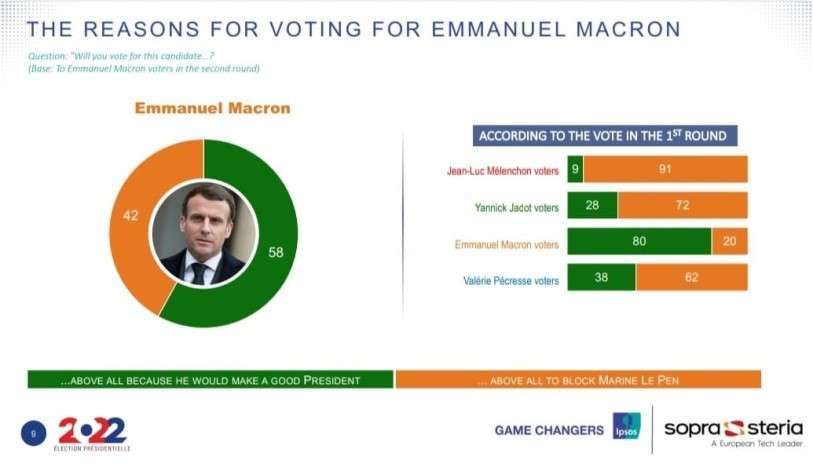

There is evidence in favour of this hypothesis. Firstly, the second round of the presidential election was contested with the highest abstention rate since 1969, demonstrating that the political formula of choosing between Le Pen and Macron generates a situation of disaffection. A survey published by Ipsos also shows that 42% of the vote for Macron is a tactical vote. In other words, it is not motivated by the belief that he would be, and has been, a good president, but by the desire to block Le Pen's access to power.

The polling house Elabe goes one step further. One poll shows that 55% of French people say that Macron's re-election is bad for the country. In addition, 61% of those polled say they would prefer a parliamentary majority opposed to the President. It is quite clear that there is a window of opportunity for the legislative elections and even the Matignon.

The Macron of today is no longer the flamboyant ex-minister with an outsider's halo who seized power in 2017. On that occasion he won a super-majority in the legislative elections, which only Les Républicains, heirs of Gaullism, survived with some dignity. The difference in votes between those presidential elections and the recent ones testifies to the president's political wear and tear. After a five-year period marked by the pandemic, but also by unpopular measures that unleashed huge social unrest, such as the Yellow Vests, it seems unlikely that Macron will be able to ride the euphoria of his triumph in the same way as he did five years ago. All the more so when the playing field for the election of deputies is reopened to all parties; in other words, he can no longer present himself as the only chance to stop the "bogeyman" of the extreme right.

However, Macron's atrophy of political muscle should not be taken for granted. After all, he finished the first round of the presidential election as the force with the most votes, in an election where conscience is more important than tactical voting.

Correlation of forces and incentives: the different scenarios that are opening up.

It should be recalled that, officially, it is the President who appoints the Prime Minister, in addition to his government. In the past, the fact that cohabitation governments were formed had to do with a kind of sense of fair play on the part of previous presidents, who handed over Matignon to the winners of the legislative elections, something they were not obliged to do. Nor is Macron, who could keep his current ministers by provoking an institutional blockade that would keep them in office, in the purest Rajoy style. Or blackmail Mélenchon for an investiture in exchange for nothing, on pain of being publicly pointed out as responsible for the institutional chaos, with Le Pen out of the equation when it comes to reaching pacts.

It is also worth asking whether Matignon, as well as being possible, is desirable for the aspirants. The shift to the left that Mélenchon wants to make in France's social and economic policy is bound to meet with enormous resistance. From employers, certain sectors of senior civil servants and Brussels itself, spurred on by the attitude of mistrust and defiance that the left-wing leader publicly professes to him. An already Herculean task if he were occupying the Elysée. Let alone with the President added to the list of enemies.

As for Le Pen, integrating herself into the management of the state without full powers, and therefore with restrictions, would make it difficult for her to maintain a discourse with which she wants to present herself as the scourge of the establishment, in the purest Trump style. An outsider image that is ironic, given that he leads a party with a large number of voters that he inherited from his father as if it were a tobacconist's shop.

Even so, holding the post also has its incentives. It implies a huge responsibility in the management of the state, and therefore a valuable CV when it comes to presenting a 'presidential' profile. It should not be forgotten that Macron dismantled the traditional French political system, absorbing every element of the old parties that seemed recyclable. Once he had done away with the old parties and their old certainties, he emulated de Gaulle's strategy, addressing society in terms of "either me or chaos". However, term limits prevent him from running for a third time. Lacking potential successors in a party entirely centred on his personal figure, it is very likely that his space will not be able to give birth to a candidate "of order" in 2027. For anyone aspiring to be that candidate, the Matignon experience may play a key role.

Regardless of which of these rationales they may have leaned towards in the aspirants' war rooms, it will have little effect on their campaign speeches. Even if they decide that it is too early to enter the Executive, the only possible public approach is that of victory. To crown themselves as The Opposition, and not simply an opposition party, they will need a respectable number of legislators.

Moreover, it is not just a question of image. The key to the process is that it could be the definitive reorganisation of French politics. The old parties have the presidential results of ecologists (6%), or even Trotskyists (1-2%), but they still control regional governments and most municipalities. This means that elected politicians, trusted officials and advisors form a huge territorial network that has its source of sustenance in politics. A very powerful machine if it can be mobilised for an election. The moves to achieve a pact between Mélenchon and the socialists point in this direction. Articulating a reorganisation of the left as a historic bloc around his figure will depend to a large extent on whether his electoral traction in the legislative elections offers any hope of resurrecting the decapitated socialist apparatus.

The same model can be applied to Le Pen and the conservatives. He will also need to retain the vote that Zemmour absorbed in the presidential elections, in order to condemn him to irrelevance and destroy his party by taking advantage of its newborn fragility. It is no small matter to get rid of his only rival in the far-right space.

But a speech calling to vote to be an ignored voice with many MPs does not mobilise. Nor does defining the dynamics of relations between parties in an ideological bloc encourage people to vote. We have to go out and win. A government to be won, a change in the way the country is run; these are victories. This is how suffrage is mobilised. As in Machiavelli's metaphor of the archer, there are distances that an arrow can only reach if it is shot upwards. Even if the aim is not to aim for the sky, but for the trajectory of the parabola to make it reach further.

Luchi Dolisnii, political advisor. Graduate in History and Master in Marketing, Consultancy and Political Communication at the USC.