The language of northern Morocco or the luck of having two languages in one

One of the most obvious manifestations of this multiculturalism is the language spoken in these parts, which has been moulded over time to become a dual language, ‘two languages in one’.

There is no doubt that the frequent and widespread use of words and phrases of Spanish origin by northern Moroccans responds to certain emotional and/or intellectual needs shared with their neighbours on the other side of the river, the result of a long and extended life in common.

De Musset said that the only true language is the kiss. This is called ‘busa’ in this geographical area, in Morocco from one end to the other, and everywhere in the Arab countries. It is not for nothing that it is insisted that a well-chosen word, no matter what language, can save not only a hundred words, but a hundred thoughts.

And it is not for nothing that it is said that languages, like religions, live on heresies and borrowings.

If the genius of all dialects lies in their ability to adapt words from other languages to their own phonetics and integrate them into their daily use, the speech of northern Morocco, and that of Tetouan in particular, goes further, sometimes daring to attribute different uses to the original terms in Spanish.

These ‘wrong’ pronunciations and usages are even shared by natives with a high level of Spanish language study. A widespread error, says the Arabic proverb, is worth more than an abandoned success. To put it bluntly, bad money always ends up driving out good.

And thank goodness for that because, as Alfonso Reyes, the great Mexican writer, jurist and diplomat, rightly said, if the educated were entrusted with breathing life into languages, Latin would still be spoken in Western Europe.

‘Nolens volens’, dialects always give better offspring because they reject inbreeding and break free from purity.

Having said that, let's get down to business. Let's take a look at this dialect that is as tasty as it is peculiar. Here is a first sample:

‘I'm not lying, I've been to the restaurant on the beach in Rincon, a group of us, we had a great time, fried fish, squid, sole, whiting and prawns, we even had a platter of sea bass rigamonte, sea bream and grilled sea bass, shell and anchovy tapas, croquettes and tortilla skewers. For dessert, crème brûlée, flan and fruit flan with pineapple, strawberry, kiwi, mandarin and chin. The waiters are professional and a tip is expected.

There is no doubt that half of the voices in this conversation about gastronomy are of Spanish origin, but what is most suggestive is that this linguistic miscellany extends to all areas, including children's games and the accompanying songs, although it is true that their number has progressively decreased since the eighties.

I am not saying that 50% of this dialect comes from Spanish, that would be an exaggeration, although, as the Arabic saying goes, exaggeration makes things clearer. In truth, we are talking about around 20%, in other words, a very broad and interesting linguistic corpus that has not yet received the attention it deserves.

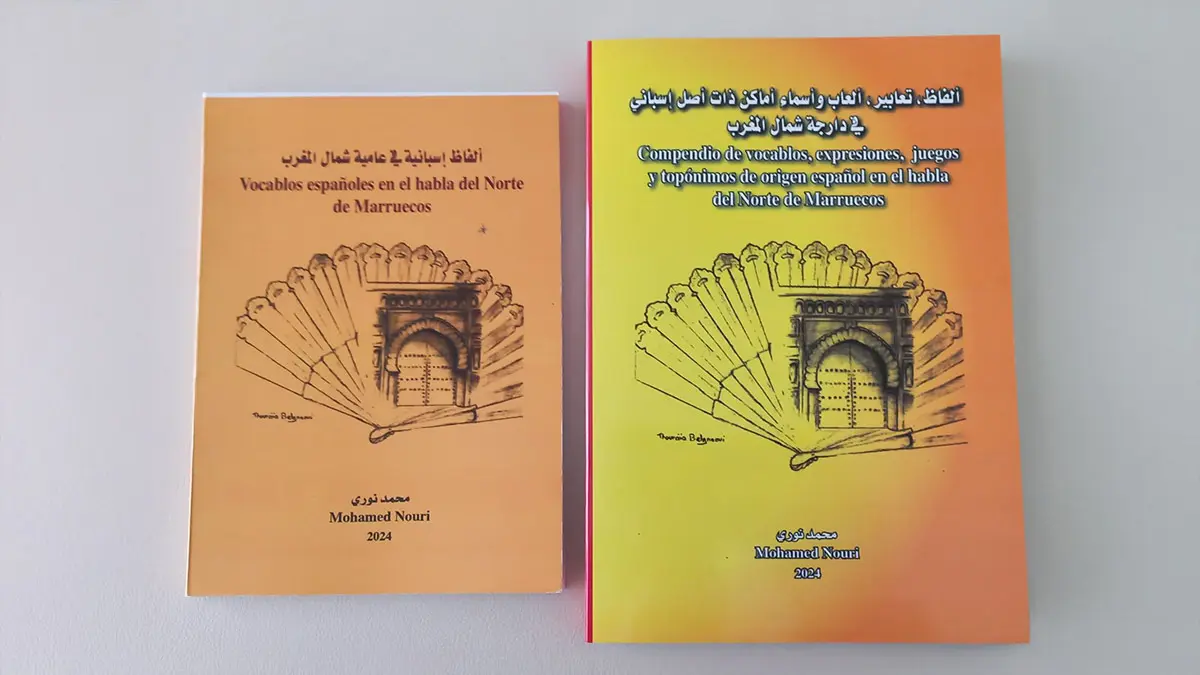

Two books celebrate this legacy that deserves to be proclaimed as an intangible heritage of humanity

Born and raised in Tetouan in the mid-sixties, I grew up exposed to the resonance of these words, phrases and children's games that sprang from the Spanish language. Today, aware of the unique richness of this legacy, but also of the erosion it is suffering for various reasons, I have set out to document, analyse and disseminate this treasure through the publication of two books (awaiting a third), namely:

- Spanish words in the speech of northern Morocco.

- Compendium of words, expressions, children's games and place names of Spanish origin in the speech of northern Morocco.

The reasons that have led me to undertake this task have been with me for almost half a century. Throughout all this time, more than once I had to stop, in front of each of these words, in continuous attempts to reach their depths and discover their forms and etymologies, noting down everything that occurred to me, waiting for the right moment, which would come one day, to offer them up like a ripe harvest born of painstaking effort.

And that day came, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Confined, deprived of my freedom, and watching very dear people disappear from one day to the next, I remembered two great characters who have inspired me a lot throughout my life, Albert Einstein, who advised never to keep in your head what fits in your pocket, and Henry Todd, who invites us to leave everything here before we go. Machado alluded to something similar in his beautiful quote: ‘In matters of culture and knowledge, one only loses what one awaits, one only gains what one gives’.

Let's get to work, I said to myself!

Objectives of these works:

Among the most outstanding, we mention:

- First: to collect, disseminate and safeguard this rich and abundant legacy.

- Second: to offer Moroccan and Spanish readers the chance to enjoy a leisurely and enjoyable read of a collection of terms and expressions of Spanish origin that they use in their daily speech, clarifying the differences in pronunciation between the different categories of the population and between cities.

- Third: to offer readers and researchers on both sides of the river, thanks to the classification into fields, the possibility of directly accessing the word, knowing its origin, its meaning or meanings, whether or not it has undergone any changes, its derivatives, the expressions in which it is used, its etymology, etc.

- Fourth: to specify the magnitude of the linguistic influence in each area and thus delimit the nature of the linguistic and cultural vectors in the chosen period of time.

- Fifth: to help them discover many words derived from Spanish but adapted to the local linguistic construction such as sabniya (sabanilla), kuw.waj (to limp applied to the game of ludo), m-ganchar (hooked), m-gashtar (worn), b-shneja (cactus) etc.

- Sixth: exploring words that are no longer used in modern Spanish but are still alive in the dialect of northern Morocco. Such is the case of bac.cha (a procedure for straightening hair), l-bufia (police van), polo (ice cream), etc. Others are of Caló origin that became part of the local language with the arrival of the gypsies during the protectorate, such as chinorre, n.naja (la naja) and ¡nanay!

- Seventh: finding out about the new local uses of certain words of Spanish origin such as chupar (to steal), l-kupia (la chuletilla) (the cutlet), peson (marica) (faggot), chap.pu (trabajo) (work), ṭ.ṭirna (el/la acomodador/a) (the usher), etc.

- Eighth: to collect a large number of words that made an exciting round trip between the two shores of the Strait of Gibraltar. Of Arabic (and sometimes Persian) origin, they were adapted to Andalusian and Spanish phonetics in general, only to end up in northern Morocco thanks to the arrival of the Moriscos and the Spanish, only to adapt again to the local phonetics. Such is the case of l-kay.yaṭa, l-manaque, n.nibar, l-paka, p-rgaṭa, r.rdoma and others.

- Ninth: to discover a good number of children's games inherited from the time of the Protectorate. There are children's games such as horse jumping, lame king, handkerchief, l-kor (marbles), salvo, pater (batel), and also girls' games such as piola, piso (hopscotch) and salta or lastic (elastic band). Unfortunately, some of these games are no longer played as much in northern Morocco as in Spain.

As a conclusion

The dialect of northern Morocco in general (and that of Tetouan in particular) is the chemical equivalent of an ‘absorption surface’, a space, in this case symbolic, where several languages react, essentially Arabic and Spanish, to create a new product, a hybrid concoction full of loanwords that translate new needs.

In fact, just as the adoption of thousands of words of Arabic origin by the Spanish language responded at the time to the need to name new things and modern customs alien to that reality, the impressive number of words and phrases of Spanish origin in the dialect of northern Morocco respond to the same demand to name the manifestations of a new modernity.

To conclude, it should be noted that, while many of the words and expressions collected in the two works are still widely used by different generations, others, however, are exclusive to generations born before the eighties of the last century. Consequently, it is not known whether they will continue to exist or whether they will die out with the disappearance of these generations.

For this reason, it is extremely important to safeguard this very important legacy from the oblivion and systematic erosion it suffers for various reasons that we explain at the end of the second book.

Using the same terms and expressions means sharing the same psychic-emotional register. It was not for nothing that the historian Mohamed Ibn Azzuz Hakim, may he rest in peace, said with brilliance and insight: ‘The Moroccan is an Islamised Spaniard and the Spaniard a Christianised Moroccan’.

It also means sharing memory, the only paradise from which we cannot be expelled (Johan Richter).