Pandemic adaptation of economic crime to cyberspace

Economic crime is either an end in itself or a stepping stone to other goals. On that basis, this article seeks to capture the changing trends in crime as a result of the pandemic, confinement and need for social distancing. Several formal and informal publications note that, to a large extent, crime has shifted from physical space to cyberspace because it is in cyberspace that the crime triangle is most notoriously fulfilled: motivated offender, propitious victim, and absence of a vigilante (Felson & Cohen, 1979). Today, cyberspace is where many work and/or school, but also everyday activities take place; thus, the opportunities for cybercriminals are increasing.

The crimes are not new. However, the coronavirus has expanded and/or created more scope for cybercriminals in different areas, including economic crime.

Making money may be the cybercriminal's ultimate goal, but it may also be an intermediate step to achieve another goal. Either way, the economic sector of the victim person, group, company or state is affected to a greater or lesser extent.

According to INE (2019), in Spain, thefts and burglaries in homes or other establishments are the most committed crimes in comparison with the rest. However, it will be quite revealing to make a new comparison with the statistics to be published in 2020 because many professionals from different fields and preliminary research already foresee a decrease in these crimes and an increase in cybercrime as a result of the pandemic caused by COVID-19 (Europol, 2020).

Before detailing and presenting some specific data, we must distinguish between four types of adaptation in terms of delinquency. According to Miró (2012), we can distinguish between typological adaptation, target adaptation, technical adaptation and place adaptation. The first of these is the response of criminals to the blocking of a specific type of crime; they adapt and go on to commit completely different crimes. Target adaptation indicates the change of victim they make depending on their level of vulnerability. The next adaptation refers to the use of new techniques, strategies or tools to circumvent emerging barriers. Finally, location adaptation refers to a shift of criminal activity from one area to another.

Taking into account the four types of adaptation mentioned above, data relating to the topic in question will be highlighted. As already mentioned, the pandemic, confinement and social distancing have led people to carry out their daily and work activities from home, in particular from their personal computer, laptop or mobile phone. In other words, the confluence previously found in physical space has shifted to cyberspace, with all the risks and opportunities that this entails. In this sense, it is coherent to think of a decrease in street crime and an increase in cybercrime (typological and technical adaptation).

Fraud and economic scams carried out online already have a previous track record, although the registration of fraud in purchase and auction has risen more than expected: 52% from 2019 to 2020 (Miró, 2021); moreover, the curious thing is that it is maintained in this way, unlike other forms of cybercrime, which rose by 43% (Miró, 2020). The reason may be that online shopping was already established in society, confinement has only accelerated the process and the need for social distancing is helping it to stay definitely.

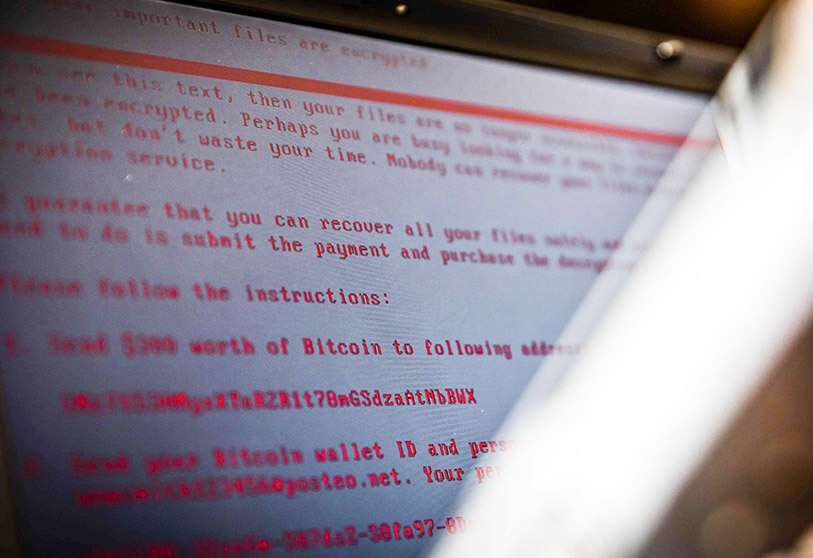

On the other hand, ransomware and phishing crimes, denial of service attacks and the creation of malicious domains are not new either. However, international research points to an increase in cybercrime in three sectors, including the final or instrumental economic crime sector and, within this, the crimes mentioned at the beginning of the paragraph (Miró, 2021). These crimes have undergone an adaptation of purpose and place, which is why they will be treated as new economic crimes in cyberspace.

To conclude, however, it is necessary to highlight the technical adaptation of cybercriminals: they use social engineering related to the coronavirus to ensure that the victim person, organisation, or state participates in the damage to their own capital or economic sustenance.

Rather than new forms of crime, there are new areas that cybercriminals have entered and new targets they are targeting for financial gain using the same techniques mentioned above: social engineering, malware, deception.

The healthcare system along with treatment and vaccine research centres became valuable targets due to the urgency of averting a health catastrophe. There were 70% more cyber-attacks in this sector compared to other sectors, with the hotel sector being the one that stood out due to a decrease in cyber-attacks (Edward, 2020).

Another new target for cybercriminals is individual employees as teleworking has become necessary due to the need for social distancing. The intention of these criminals is to gain access to the organisation through the employees for financial gain as an ultimate goal or as a means to harm the company or institution. The point of access has changed due to the increased vulnerability of individual network and technological devices compared to corporate ones.

As for the change in the cybercriminals' area of operation, it should be noted that this has come about as a result of the social uncertainty resulting from the coronavirus. People's desire to stay informed and safe makes them susceptible to phishing, ransomware and/or scams. The new line of social engineering makes use of advertisements and spam about the sale of personal protective equipment or medication against the virus. In some cases, these products are purchased without being delivered or in a defective form and therefore the price becomes exorbitant (scams); in other cases, the ultimate goal is to get the person to click on the advertisement to download and install malicious software and thus obtain personal data such as bank card numbers (phishing). Also, among the cases of ransomware, a crime that consists of hijacking data on a network to demand a financial ransom for it, the so-called Netwalker (UDIMA, 2020) stands out.

Finally, it is necessary to mention the significant role of cryptocurrencies in economic crime in cyberspace. When any economic crime is committed using cryptocurrencies, the investigation of it is made more difficult at higher levels because, being a relatively new type of money, law enforcement agencies have not yet developed adequate tracking tools. However, this does not detract from the fact that there have already been cases in which frauds involving cryptocurrencies have been solved (example in El País, 2021). On the other hand, it is worth noting that cryptomarkets have also seen a change in trend, with surgical masks and COVID-19-infected blood being sold rather than computer viruses and credit card data (Buil-Gil et al., 2020).

The common factor in all the adaptations in the field of crime is the sudden appearance of a virus that plunged all countries into confinement, triggering a move to the digital world without taking the necessary precautions.

In this sense, forms of prevention, previously conceived and developed for crimes in physical space, have to be restructured and implemented in cyberspace. There are three levels of prevention. Primary prevention should be dealt with by governments through the dissemination of these new crime trends, as cyber criminals often use the name of government departments in an attempt to make themselves more credible to their victims. Secondary prevention has to be solved by the organisation or institution for its own environment, by making its employees aware of the possible forms of cyber-attacks against their company in particular, and by training them adequately on the new platforms used in the performance of their work. Finally, tertiary prevention is the responsibility of the judicial and penitentiary system, although the reaction at this point might be too late and the damage might be enormous.

Naomi Vilchez, criminologist, and collaborator in the area of economic crime at Sec2Crime.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cohen, L., & Felson, M. (1979). Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588-608. DOI:10.2307/2094589

David Buil-Gil, Nicholas Lord, Emma Barrett, Daniel Dresner and Brian Higgins (2020). Profiting from pandemics: COVID-19, changing routines and cybercrimes. Recuperado de: http://blog.policy.manchester.ac.uk/digital-futures/2020/03/profiting-from-pandemics-covid-19-changing-routines-and-cyber-crimes/ [Revisado el 16/16/2021]

Edward, G. (2020). Number of breached records surged by 273% in 2020 Q1. AtlasVPN [en línea]. Recuperado de: https://atlasvpn.com/blog/number-of-breached-records-surged-by-273-in-2020-q1 [Revisado el 16/06/2021]

El País (2021). La Policía destapa una estafa de más de 7 millones en criptomoneda. Recuperado de:

https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2021/01/05/mercados/1609871609_703874.html [Revisado el 16/06/2021]

Europol (2020). Pandemic profiteering: how criminals exploit the COVID-19 crisis. Recuperado de: https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-documents/pandemic-profiteering-how-criminals-exploit-covid-19-crisis [Revisado el 15/06/2021]

INE (2019). Estadísticas nacionales de delitos según tipo. Recuperado de: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=25997&L=0 [Revisado el 15/16/2021]

Miró, F. (2012). El cibercrimen. Fenomenología y criminología de la delincuencia en el ciberespacio. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

Miró, F. (2020). Impacto del covid-19 en distintas formas delictivas: covid-19 digitalización y delincuencia. Fundación para la investigación aplicada en delincuencia y seguridad, 11-13.

Miró, F. (2021). Crimen, cibercrimen y COVID-19: desplazamiento (acelerado) de oportunidades y adaptación situacional de ciberdelitos. IDP: Revista de Internet, derecho y política, 32. Recuperado de: Delincuencia, ciberdelincuencia y COVID-19: desplazamiento (acelerado) de oportunidades y adaptación situacional de la ciberdelincuencia | IDP: Compartimiento, ley y política del Internet (raco.cat) [Revisado el 16/06/2021]

UDIMA (2020). Crisis COVID-19 y delincuencia ¿Qué ha cambiado y qué cambiará? Recuperado de: https://www.udima.es/es/articulo-delincuencia-criminologia-coronavirus-por-abel-garcia.html [Revisado el 16/16/2021]