The perfect dictatorship in Mexico again?

However, the expression, referring to the Mexican system of government that allowed the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) to remain in power uninterruptedly for seventy years, was coined by the recently deceased Spanish-Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa.

It was 1989 and the Berlin Wall had just fallen, its rubble heralding the imminent collapse of the European communist dictatorships under the relentless power of the Soviet Union. In Latin America, these events were followed with great attention and, among many other forums, Octavio Paz organised three intense days of debate in August 1990, under the generic title ‘The 20th Century: The Experience of Freedom’, at the opening of which he called for intellectuals on both sides of the Atlantic to unite in the house of the new democracy.

Paz coordinated a spectacular cast of speakers from America and Europe: Milosz, Revel, Michnik, Krauze, Semprún, Bell, Castoriadis, Heller, Kolakowski, Ignatieff and Vargas Llosa. The debate was broadcast live by the powerful PRI television network Televisa, and when it was the future Nobel Prize winner's turn to speak, he said: ‘Mexico is the perfect dictatorship. This is not communism or Fidel Castro. It is Mexico,’ implying that he was referring to the machinery of political corruption that allowed the PRI to enjoy uninterrupted power. Periodic elections, whose results were known in advance, helped to give the regime a veneer of democracy.

That debate also took place in a context of change in Mexico and the Latin American continent. The year before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Mexican PRI had split due to the dissent of Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, who had not only challenged the party's official candidate, but had also apparently defeated him. The PRI rallied, refused to relinquish power and unleashed harsh repression against the sectors that supported the dissidents. It was not until the following year, 1989, that the PRI acknowledged for the first time that it had been defeated in the Baja California gubernatorial election.

Since those events, Mexico has elevated presidents from other parties to power, some of which emerged from splits in other parties. The party that currently dominates the country's political landscape is the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), founded in 2011 by Andrés Manuel López Obrador, whom Mexicans refer to as AMLO.

As the absolute ruler of the executive and legislative branches, AMLO pushed through a radical reform of the judiciary at the end of his presidency (2018-2024), arguing that it would make the judiciary ‘democratic’ by allowing judges and magistrates to be elected by popular vote. Under this sacred principle, any candidate who is supported by a majority of popular votes can aspire to hold the positions of local judge, magistrate or Supreme Court minister.

This Sunday, 1 June 2025, these elections were held to provide an initial contingent of 881 federal and local court judges, for which 3,422 candidates stood. According to numerous corroborating testimonies on social media, a large number of these candidates enjoy the approval of drug lords, when they have not been directly imposed by them. It was AMLO who changed the repressive policy towards narco-terrorism, under the slogan ‘hugs instead of bullets,’ which has resulted in a significant percentage of Mexico's vast territory being under the control of organised crime.

The current president of the country, Claudia Sheinbaum, who has wholeheartedly embraced this radical change in one of the powers that shape society, does not seem averse to the formation and consolidation of a monolithic power. Although there have been many cases of illegal deals between judges and criminals, the law recognised their independence to prosecute and sentence without pressure. Now, at least among the opposition media, there is little doubt that the new judiciary will resemble those of Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua more than those of democracies where checks and balances, accountability, transparency and freedoms still prevail.

Organised crime, which was in its infancy when Vargas Llosa coined the term ‘perfect dictatorship’, now brazenly displays its power, including its impunity in those territories it dominates through pacts with those in power or by imposing irresistible violence.

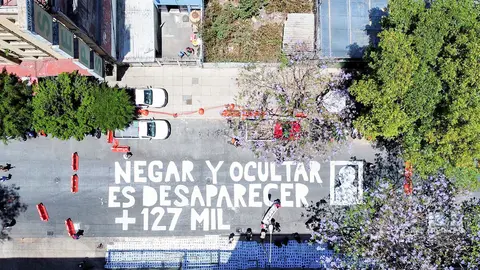

According to the Zero Impunity Movement, in recent years, only 14 out of every 100 crimes reported were solved, meaning that the probability of a crime committed in Mexico being solved was only 0.9%. The Attorney General's Office itself estimated that 95.5% of crimes went unpunished.

Given the very low turnout in the vote for the new judiciary, there does not seem to be much confidence that such overwhelming figures will change the picture. Elections, incidentally, which are not counted by the usual officials and whose results will not be known until mid-June.