No will for change in Algeria

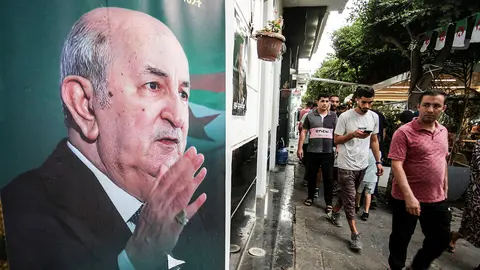

To win with 94.65% of the vote now, when in 2019 he was elected with 58% of the vote, seems too pharaonic a triumph not to be questioned. If, moreover, we decrypt the figures offered by the ANIE, the accounts throw up some strange unknowns.

Let's see: there were 24 million registered voters, 48% of whom appear to have exercised their right to vote. That represents some 11 million votes, of which 5 million would have gone to Tebboune. Since the three rivals of the presidential candidate barely represent 5%, this means that there would be 5.6 million blank votes. In other words, this segment of blank voters would be the real winner of the elections, unless the ANIE has counted them in favour of the overwhelming winner.

As for the turnout, there is also room for some suspicion. The supposed 48% turnout is too high because the voter turnout in some wilayas was not even testimonial: 4.36% in Tizi Ouzou; 3.75% in Bejaia; less than 1% in Kabylia; in short, to reach this supposed 48%, it would have taken a turnout in the rest of the country whose crowds could have been seen even from space.

Without clearing up the first and fundamental unknowns, it seems clear that when the regime claims that Tebboune won the Soviet-style election with almost 95% of the vote, what it is announcing is that nothing is going to change in the second five-year term of the current Algerian president.

Politically, the repression of the Hirak movement unleashed by Tebboune as soon as he took office will remain as fierce as ever, if not even more brutal. The army, whose ‘nihil obstat’ is a prerequisite for running for president, wants this. It was the institution that decided to put an end to Hirak ‘whatever it takes’ when demonstrations gathered more than ten million people protesting against the regime's immobility. Of course, the vast majority of those protesting were young people, in a country where 70 per cent of the population is under 40.

As a result, as Xavier Driencourt, former French ambassador to Algiers, told Le Point Afrique, ‘the [Algerian] military have suffocated any attempt to get the younger generation to come out of their heads, and they are either in prison or under surveillance’.

Driencourt stresses the international isolation in which Algeria finds itself, which ‘has no diplomatic relations with Morocco, has practically frozen them on its flank with the Sahel, is at odds with the junta that rules Mali, has withdrawn its ambassador in Paris, and is also experiencing turbulence in its relations with Russia’. All of this paints a picture of an isolated country that only makes its voice heard on the international stage with regard to Palestine and Western Sahara.

If we add to all this the fact that the country's public finances are practically only fed by oil and gas, the immense youthful strength of its population is increasingly giving in to the temptation to emigrate in one way or another, an issue that has a direct impact on Europe's southern border, mainly Spain and France.

Although Algiers announced severe retaliatory measures against France when President Emmanuel Macron joined Spain and the United States, among others, in recognising Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, these have not yet taken place beyond a few administrative hurdles, basically to delay the installation of new diplomats in the country and to block the removal of the belongings of those who are leaving for a week or so.

The Algerian president was scheduled to make an official visit to France, a visit that has never been announced or cancelled. There is now talk that it could take place before the end of September. If it does, the portfolio of issues to be discussed is extremely thick: from security in the Mediterranean and the growing illegal migration flows, to the upcoming votes in the United Nations, of which Algeria is currently a member of the Security Council.