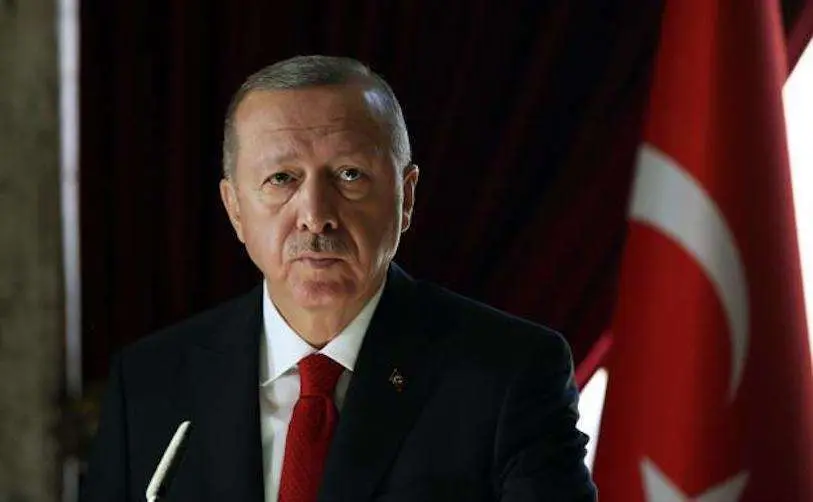

Erdogan, and the shadow of Suleiman

After the Turkish parliament's decision in early 2020 to send troops to Libya, there is little doubt that Erdogan's overall foreign policy approach is based on the geopolitical theory conceived by Turkish intellectual and former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu, a regional architecture designed for the gradual recovery of the power once held by Turkey, through a "neo-otomanism" that accelerated its deployment after the European Union slammed the door on Turkey's hopes of becoming a Member State, and which found in the rise of the Arab revolutions, Obama's indecisive external action, the EU's military irrelevance, and Trump's international incoherence, the breeding ground.

Erdogan has been able to play with some skill this expansionism in the Mediterranean, to gain a foothold from within, although this has often led him to act first, and think later. One example of this was the arrangement with Russia whereby he was able to acquire the Russian S-400 antiaircraft missile defence system, and to engage in a precarious alliance for territorial control of Syria. So precarious, in fact, that events in Idlib, where Turkish troops have suffered a serious setback at the hands of the Syrian army - supported by Russian aviation - have led Erdogan to ask Trump to obtain Patriot anti-aircraft missiles. These miscalculations were based on the false premise that supporting Islamist elements in the opposition to Bashar Assad would create useful client networks for his "neo-Ottoman" project, and in the process give him a strategic advantage in controlling the Kurdish threat. Now, however, the escalation of tensions in Idlib has unsettled Turkey, making it easier for the Syrian Kurds to become a key factor in US and Russian calculations to influence Turkey, and causing an internal problem for Erdogan because of the refugees displaced from Idlib.

It is the same geopolitical ineptitude that has prompted Ankara to support extremist groups in Libya, Tripoli and Misrata, despite the arms embargo imposed by the United Nations, which has seen Turkish support for the Libyan Dawn coalition: Turkish support (in synchrony with Qatar, where Turkey has a military base) reinforces Islamists within Libya, and logically triggers alarms in Egypt, a historical ally of Russia, and very aware of the relevance of latent intra-Sunni conflicts, which place Cairo on a collision course with Ankara, for whose plans to make Libya the central geographical pole of its "neo-Ottoman" project, Haftar is an impediment, which is accentuated by the gas fields in the Levantine waters.

The minimal agreement with Russia on Libya does not eliminate the risks that Turkey runs, especially given that Turkey's push beyond its borders lacks consensus, not only among its internal political elites, but also between them and the army, which leads one to conjecture that Erdogan's primary motivation lies in the attempt to unify the whole of the Turkish people, believers and laity, around the common cause of their "neo-Ottoman" vision, which serves as a bridge between both sensibilities, bringing together religious interests with the economic elements of a more classical nationalist project, endowed with the attributes of the pan-Arabism of Nasser and Gaddafi.

The truth is that, as has been seen in Idlib, despite being a strategically located Muslim-majority country, and equipped with NATO's second army, Turkey does not have sufficient specific weight to exploit its interests without having to confront other players who are aware of its weaknesses. Just as Bashar Assad feels strong, confident that Russian and Iranian support, coupled with American disinterest, makes it very difficult to remove him from power, Russian and Egyptian support for Haftar only augurs well for the spillover of the Libyan problem onto other North African borders, creating regional frictions whose dynamics Turkey does not have the capacity to control, and which can easily turn against its own national security, and of course, its economy; On the one hand, Turkey has been forced to buy Russian military equipment to circumvent US tariffs and embargoes, but on the other hand, it cannot afford to let American assets out, nor enter into direct confrontation with Russia. It is precisely what the hostilities in Idlib show that there are real limits to the convergence between Turkish and Russian interests, something that Erdogan would do well to take note of, before taking another leap forward in Libya, which may end up making it more vulnerable within its own borders, and ultimately precipitate its downfall.