The Happy 80s and La Movida madrileña

"If you lived through the 80s and you still remember it, you didn't live through them". This is a phrase by José Tono Martínez, which made his fortune, to sum up a decade marked by what came to be known as "the Movida madrileña". In Spain, and most emblematically in its capital, democracy had exploded, refuting the many prophets who predicted a return to the Civil War, to the torn confrontation between Spaniards, to the delight of so many foreign observers who looked at us, condescendingly, through the prism of intolerance.

The truth is that at the end of the 1970s and well into the 1980s there was a kind of vital creative, cultural and social moment and movement, of popular participation, which changed the rules of the game of what was then understood as culture, until then patrimonialised by traditional elites. It was the high point of the modernity-postmodernity debate, when high culture allowed itself to be contaminated by low culture, and became fluid, hybrid

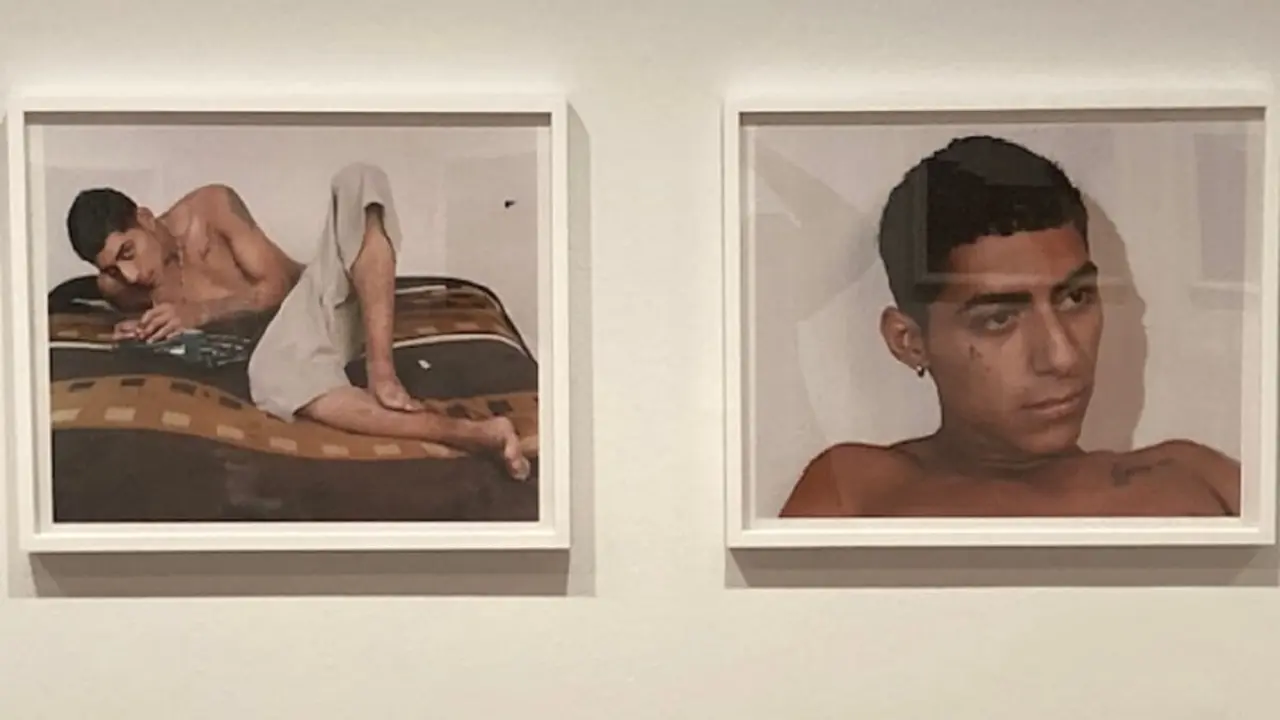

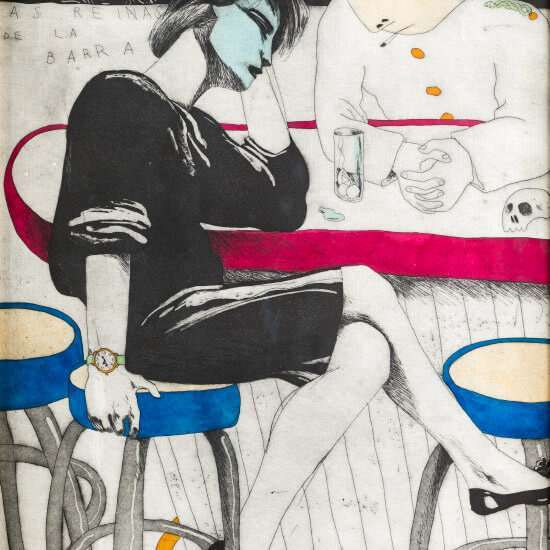

Modern music, pop, rock, punk and other unusual music; the world of comics and street "fanzines"; fashion and clothing fashions, designed or invented; the design of objects applied to all the decorative arts; the new type of cultural magazines, such as Dezine, La Luna Madrid, Madrid me Mata, heirs to Nueva Lente; theatre, literature and cinema, which cease to be vindictive art and essay or vindictive art and essay, and are no longer art and essay or art and essay and became Celestinesque, Pasoliniesque, minstrelsy tragicomedy; art, performance and photography, the latter finally accepted as art. All of this made up that iconographic fresco that came to be called, without the consent of the protagonists, La Movida. And which, again without general agreement, is usually confined to the decade from 1978 to 1988.

As the author of the sentence that heads this chronicle, former director of La Luna de Madrid and curator of this exhibition, points out, "some 40 years have passed since those drifts, and little by little they are becoming a museum". The epicentre of La Movida was Madrid which, emancipated from its capital status associated with the defunct dictatorship, projected its centripetal wave throughout Spain, "attracting the numerous free electrons from other cities". José Tono says that "without seeking it, the last total movement of a 'national', state character was thus produced: a transitory, imaginary state of mind, but one that has left its mark". If today we call it happy, it is because it was very free, very libertarian, very close to the recovered streets.

It would take too long to list the 40 emblematic artists in the exhibition. Most of them are part of the collective memory of those who lived through that period, if not magical, then quite unprecedented, unexpected and astonishing for classical observers and analysts. In any case, it is important to point out that a large part of the selected works, coming from private collections, have scarcely been seen by the public, which may be an additional incentive to enjoy this exhibition, which will be open until 12 October. And for the youngest visitors, it may be a real discovery, and a discovery, perhaps an astonishing one for them, of what their elders were capable of doing and inventing.