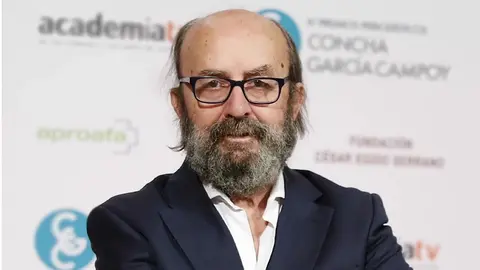

Pérez Azaústre: "Inventing a confrontation between the Machado family is an indignity"

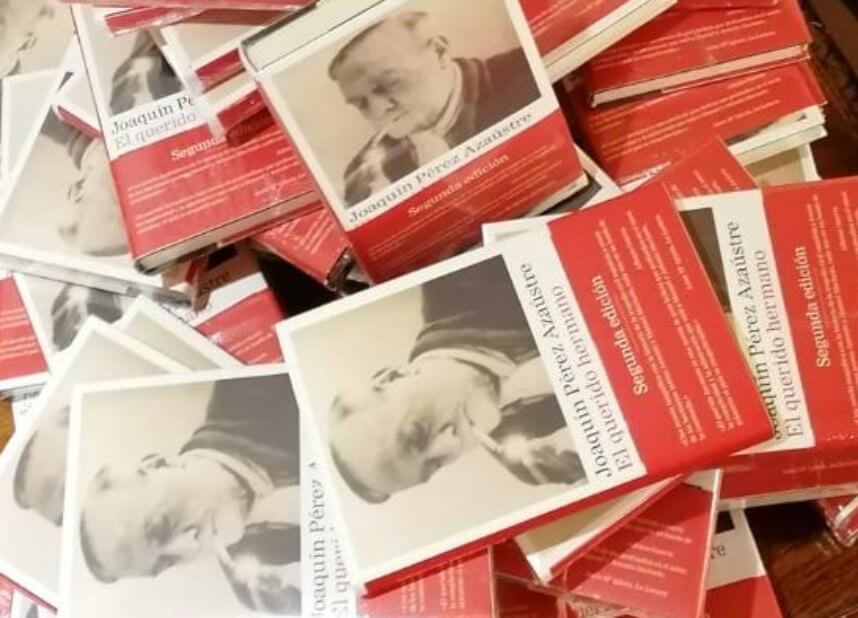

Joaquín Pérez Azaústre closed 2022 with two important pieces of news: his novels "La larga noche" (Almuzara) and "El querido hermano" (Galaxia Gutenberg) won the Jaén Novel Prize and the Málaga Prize, respectively. Both were published in 2023, which is about to come to an end. "El querido hermano", which tells the story of Manuel Machado's journey to France after learning of Antonio's death, is now in its third edition and has won two more awards: the Publishers Weeksly Book of the Year and the Cuadernos del Sur Prize for Novel of the Year.

Behind this work there are also many hours of research. The data and real facts alternate with fictitious situations and dialogues; pages in which the journalistic and poetic styles are intertwined, for let us not forget that the author is also a great poet, winner of such prestigious prizes as the Adonáis and the Loewe. Atalayar spoke to him in the Café Comercial, one of the favourite haunts of this Cordovan who lives in Madrid. In this magical place of literary gatherings and encounters, he defended the Machado brothers' brotherly love above everything and everyone, which is why he does not hesitate to say that "inventing a confrontation between brothers is only a self-serving indignity". He also spoke of the Spain that each of them represented, of Paris, of their characters, of that journey that goes beyond a simple journey, of death, and even of the amnesty.

1939. Burgos. Civil War. Manuel Machado is informed of the death of his brother Antonio in France and begins his journey to say his last goodbye. This is how "El querido hermano" begins. Did you think that this novelised journey would take you where it is taking you?

I have always had the idea of this novel in my mind. I remember a first conversation with Pere Gimferrer about it many years ago, in 2004, when I published my novel "América". But I didn't consider writing it until 2019, after winning the BBVA Foundation's Leonardo Scholarship for the project to write a novel about Manuel Machado's journey to Collioure, when I heard the news of Antonio's death, which had not been told, but also the intimate relationship of total brotherhood in literature between the two brothers. When the pandemic came, I clung to his writing like a lifeline. The best destiny has been to have the poetry of the two brothers in my life and to write about them.

Third edition and great reviews. Antonio Lucas commented: "Pérez Azaústre returns the forgotten to his place". If Antonio Machado had not died in exile, do you think that the literary place occupied by one and the other would be the same?

Let's see, when the war began in 1936, Antonio Machado was already the great poet. He is only matched by Juan Ramón, and Lorca, of course, although he belongs to the following generation. If he had lived, he would surely have occupied the same place or better, because he would have had time to write more, and his work stands out for its solidity and coherence. So probably the passage of time, evocation and distance, if he had survived in exile, could have led him to write some more extraordinary books. Another thing is that the drama of his death, on the painful road to exile, almost unable to carry his own body, turned him into a symbol of defeated Spain. The same is true of Lorca who, being younger, would have had more time to write great works.

The brothers represented the two Spains, but in his book he writes that Manuel was forced to stay in Burgos and join the uprising, "little is known about the real reasons that led him to do so and the danger to his life". Was Manuel's motivation more circumstantial than ideological?

I think that, on the one hand, Manuel Machado was already very disillusioned with the Republic because of its Soviet drift. That is why he stopped writing in "La Libertad". He received it with joy, composing a hymn for the Republic which he recited at the Ateneo in Madrid on 26 April 1931, with music by Oscar Esplá. But the Republic at that time was already closer to the radical left than to liberal democracy, which is what Manuel Machado believed in. When he was arrested in Burgos and spent two days in prison, fearing for his life, this precipitated his joining the Nationalist camp. I don't think he was very enthusiastic, but not totally impostural. At that time he already felt more conservative.

Thinking back to that Spain, do you think that the two Spains are once again present? What would the Machados family have thought of the amnesty?

It is impossible to know, but we can make some guesses. There is a letter, not from Manuel, but from Antonio Machado, to his last love, Guiomar, a name which hides the name of the poet Pilar de Valderrama. In that letter, speaking of the Republic, he tells her that nothing can be expected from the Catalan independence fighters, because they care nothing for the future of the Republic, but only to use it for their own cause. In other words: only themselves. I believe that this line of reasoning could be fully applied today.

A distant, ideological and literary image of the two brothers has been fostered. You draw a relationship of admiration, respect and love. Where is the balance?

In the truth. In the letters they wrote to each other, in the plays they wrote together, in how they always looked after each other, starting with their youthful period in Paris, around 1899, which I recount in the novel. There is not the slightest testimony or evidence of even a superficial estrangement between the two brothers. They do not communicate again after the first week of the war, like so many other broken families, because communications and telephone lines are cut. But beyond that, to try to invent a confrontation between them, when all the evidence we have up to 1936 proves just the opposite, is just a self-serving indignity.

Is the image of Manuel as a party-goer, happy-go-lucky and a lively man, and Antonio as a sad, shy and lonely man, true?

Not entirely. Antonio has a partying side, especially in his early youth in Madrid, because he frequents the world of theatre, which they were both always passionate about, and he even made his debut in a play with his friend Ricardo Calvo. Also in Paris, with his brother Manuel, in 1899, we could say that he let his hair down quite a bit. And Manuel, on the other hand, who, of course, was a great nocturnal companion, also had a very deep underground flow, which is where these two brothers always meet.

What did Paris mean to the Machados family in these pages?

The joy of living their youth in poetry, in that great fin-de-siècle Paris over which the death of Verlaine, symbolist poetry and the Dreyfuss affair still hangs. They were very happy.

"Qué me entierren en París" is the title of a poem of yours and also of an anthology. Why this somewhat nostalgic dazzle?

It means just the opposite of nostalgia or melancholy: it's a celebration, it's standing up to death and the desolation of living through joy, fulfilment, writing and love. It is a youthful poem, but I still recognise myself in the enthusiasm and desire.

Let us return to "El querido hermano", to the character Pemán, lawyer, poet, political journalist... and friend of Manuel Machado. There are those who say that you treat him with great affection, is there a reason?

I have great respect for my characters, but also distance from them, so that I can feel free when I write. As we live in this paralysing ideological correctness, which deep down is nothing more than self-censorship, motivated by fear of cancellation, there are those who are surprised to see Pemán as a character in my novel, with more light than shade, and also helping Manuel Machado. Pemán was a good poet, a good playwright and an excellent columnist. The other day I was talking about it with Anson, after celebrating Pablo Neruda and Rafael Alberti. Reading taste cannot be sectarian, it is neither healthy nor good, nor just, nor noble, to cross authors off the list by virtue of their ideology.

Another (fictitious) character is Raúl, the young Falangist who will drive the car to France. In one scene it is said that life is in books; what would his life be without reading and writing them?

Raúl makes a geographical journey as he takes Manuel Machado and his wife Eulalia in the car to Collioure; but he also has his own inner journey, because he enters the world of the two brothers and also, timidly, their poetic works. Raúl also takes us into the intimacy of the car, but he represents that truly free reader who can approach the work of both brothers without prejudice. As for my life without books, right now I find it hard to imagine it, but I suppose I would find other ways of telling stories, for example, cinema, which has always been very present in my life.

In "Atocha 55", about the murders of the labour lawyers, "La larga noche", centred on Manolete, and "El querido hermano", death is present. What is your relationship with death?

Neither good nor bad, the normal: the further away, the better. In these novels there is an intention to recover important moments in our recent history from a non-sectarian side, because literature, and narrative in particular, can still offer us spaces for coexistence and dialogue that are no longer possible in politics.

We are talking about narrative, but you are also a poet and have won major prizes such as the Adonáis, the Loewe, the Gil de Biedma... When are you going to publish a new collection of poems?

I have one finished, but I don't know if I want to publish it yet. I'm still writing poems, especially to my son and to moments of intensity, of flight or elegy. And I will continue.

Years ago, in an interview with our dear Félix Grande, I asked him to recall some verses and he quoted Machado, Antonio: "Today is always still". Let's close with a poem, a poet, a song, a word?

It will be a pleasure. I choose this poem by Manuel Machado, which he entitled "Echoes" and which is based on Antonio's verse "Chops of the white road, poplars of the riverbank! It is written after the death of Antonio and also of his mother, Ana Ruiz. I am struck by its simplicity and deep mourning. From Antonio's verse, Manuel shakes us:

What is it about this verse, mother

that fills me with tenderness

that I cannot say it

without my heart aching...?

Chhopos of the white road, poplars of the riverbank!

What have they got, mother, what have they got

these words that sound

so deep in my breast

and so far and so near...?

White roadside poplars, riverside poplars!

What do they say, without saying anything...?

Without saying anything, what do they say?

Of these simple words

What did Antonio put in the letters?

White roadhoppers, riverside poplars!

When I take them on my lips

they reach my ears...

why do I weep without consolation?

and why do I weep without sorrow?

White roadside poplars, riverside poplars!