Tangier: a universal space of freedom and happiness

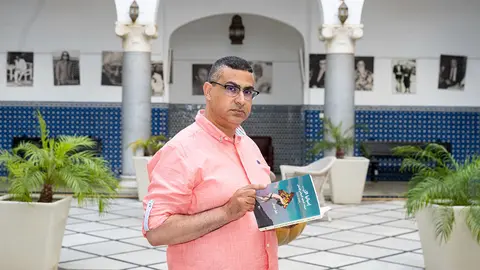

On 19 September, Javier Valenzuela had an important meeting with the city of Tangiers to renew, on the one hand, the ties that the Spanish novelist had built with the literary space of Tangiers and, on the other hand, to celebrate the release of the Arabic version of ‘Tangerina’.

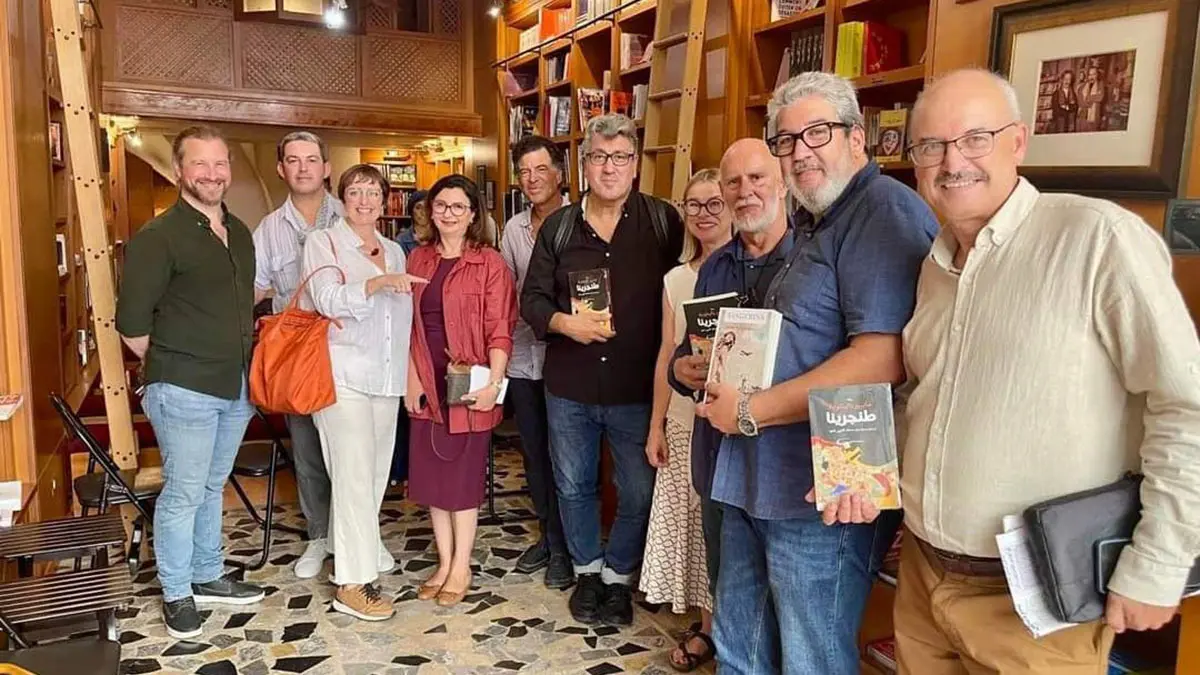

At the Les Colonnes bookshop, Javier Valenzuela accompanied the Moroccan Hispanists for the presentation of the Arabic translation of his work ‘Tangerine’ by Larbi Ghajjou. The presentation was attended by major players in Moroccan Hispanism such as Randa Jabrouni, president of the Association of Friendship and Solidarity between Morocco and Latin America.

Javier Valenzuela, born in Granada in 1954, is a Spanish journalist with 40 years of experience. The distinguished correspondent of El País in Beirut, Rabat, Paris and Washington also worked as a war correspondent in Iraq, Palestine, Lebanon, Iran and Bosnia. His professional career, chief reporter (Diario Valencia), chronicler (La Movida) and a great pragmatic libertarian interested in politics, has been reflected in his journalistic books in the form of a collection of articles, chronicles, essays, analyses and travels published between 1989 and 2021.

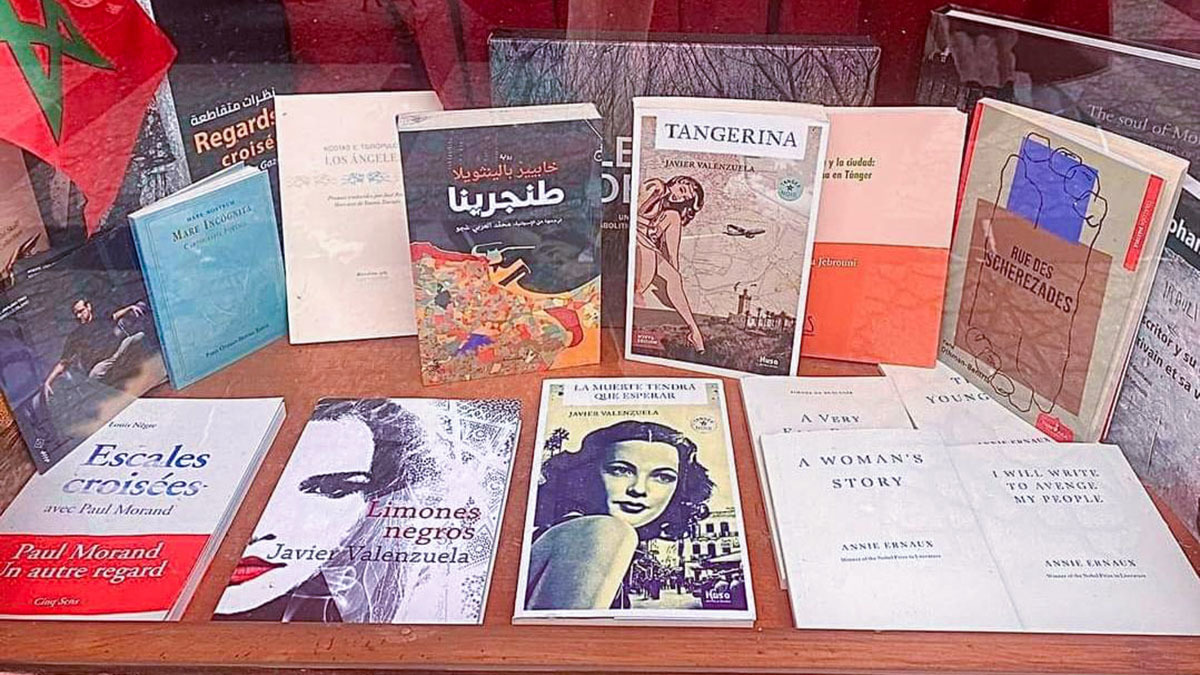

Valenzuela moved into the world of fiction with his first novel ‘Tangerina’ (2015). From there, the international city has remained a crucial axis alongside women in both the second novel ‘Limones negros’ (2017) and the recently published ‘La muerte tendrá que esperar’ (2022).

Valenzuela received the ‘Intercultura a la Convivencia de Melilla’ award in 2007, the ‘Premio de Periodismo de Cartelera Turia’ (Valencia) in 2018 and the ‘Café Español’ award in 2019 for his short story ‘Hitler en Tánger’.

Between the inspiring space, the living setting and the fundamental character of the plot, what does Tangier represent for Javier Valenzuela, the writer and the person?

Tangier is for me a space of freedom, a space where I can be myself more than in other places, and, consequently, a space of happiness.

I experience many moments of happiness in Tangiers. For its light and its vegetation, for its open and tolerant spirit, for the good humour of its people. Tangier is a microcosm within Morocco, a Moroccan city which, because of its geographical situation, its history and its present, is different from other Moroccan cities. It is more universal.

Throughout the three instalments covering different periods between 1956 and 2021, what are the themes that have marked Tangier's history? How do you assess the evolution of the city on a cultural level?

The capital of the Strait experienced a Golden Age in the first six decades of the 20th century, the so-called ‘international’ period. It became a haven for European and American dissidents and a magnet for writers, painters and musicians from all over the world. Tangier and Morocco must reclaim that past.

I think it fits well with the vision of a Morocco with roots in Africa and the Arab-Muslim world and with branches open to Europe and America. After independence, Tangier went through a period of decline, not only because the Jewish and Western communities left, but also because the authorities in Rabat left it to its own devices.

But at the beginning of the 21st century, with a new monarch on the Alaouite throne, Tangier began to experience a spectacular renaissance. The Medina and Kasbah have been tastefully restored in general, new urban and economic spaces have been created, and foreigners are once again attracted to the city, whether as residents, tourists or investors.

My trilogy ‘Tánger Noir’ tries to tell the story of this evolution through both Spanish and Moroccan characters. Like all sagas, it begins with a genealogy, the Tangiers of 1956, where Olvido, the mother of the protagonist of ‘Tangerina’, Professor Sepúlveda of the Cervantes Institute, lives. But already in this first instalment, which takes place in 2001, Tangiers is presented as poor and decrepit after decades of neglect. Then, in the next two instalments, ‘Limones negros’ and ‘La muerte tendrá que esperar’, Tangier's rebirth in the 21st century is recounted. For example, the Moroccan character Rivaldo-Messi, a street child, goes from running a street stall selling boiled chickpeas to running a modern telephone shop.

Given your extensive experience in the press and your long career in writing, how can the press serve fiction and how does it help the novelist in his or her literary work?

Journalism can help the novelist in the task of researching reality: visiting all the places on foot, talking personally to many people, being precise about places and dates, scrupulously verifying the real facts, knowing all the documentation available in books, documentaries and films, things like that. But when it comes to narrating, to telling the story, journalism is very different from the novel. I had to free myself from the corset of journalism to give free rein to my imagination to create plots, characters, scenes, dialogues.

Nowadays, with technological development, we live in a continuous conflict between truth and lies, information and ‘fake news’, appearance and reality that sometimes surpasses fiction. What do you recommend to face this daily conflict? How should the reader, the listener and the writer himself act?

As a journalist and as a citizen, I recommend what I practice: not to believe anything that comes out on social networks or in media of dubious credibility. Check everything with other sources twice, three or four times, as many times as necessary.

There is a lot of politically or economically self-serving rubbish out there. You just have to believe what people or serious and reliable media tell you, and even then it is worth verifying.

With four female protagonists, two Moroccan and two Spanish, you pay tribute to the decisive role of women in the 21st century. What is the reason for this choice? How do you see Moroccan women today?

Professor Sepúlveda is the male protagonist of ‘Tangerina’ and ‘Limones negros’, but in the third instalment of the Tánger Noir series, I preferentially give the voice to four women. Two are Spaniards living in Tangier, Adriana and Teresa, and two are Moroccans, Leila and Malika.

I love the progress in women's rights and freedoms, I think it is an essential step forward in civilisation. I admire Moroccan women very much: they are very strong, very brave and with a great sense of humour, and I am happy to see how they are making progress in the social, political, economic and cultural spheres.

In ‘La muerte tendrá que esperar’, I also pay tribute to Arab women by having the Tangerine pharmacist Leila read stories from ‘The Thousand and One Nights’ to Professor Sepúlveda at night. The Tangerine Leila becomes Scheherazade for Sepúlveda in this novel, just as Tangier is my Scheherazade in this trilogy.

Faced with a world full of injustice, wars and natural disasters, do you believe that the novelist, with his or her pen, can contribute to changing or at least softening this reality? Are you committed to the concerns of humanity, of your society?

The novel makes the world more bearable, because reading it entertains people for days, and it also makes it more comprehensible if it is a good novel.

And what is a good novel? Well, for me, it is the realistic novel that explains a certain place and a certain time, with its problems, its anguish, its joys and its hopes. With its lights and shadows. The novel that tells the reader that he is not alone in his concerns, that he is not crazy for thinking that things can be improved. And, of course, that it does all this with the best possible writing. The best of all novels of all time remains for me ‘Don Quixote’ by Miguel de Cervantes.