That project to colonise empty Spain

On the exterior façade of the ICO Foundation Museum on Calle Zorrilla in Madrid, the gigantic photograph of eight retired peasants stands out powerfully. Anonymous men, from deepest Spain, who have behind them a beautiful and hard story, at the same time ignored by the general public.

The snapshot serves as a gateway to the exhibition "Colonisation: Views of an invented landscape", which rescues from oblivion that experiment of filling large uninhabited areas of the Spanish countryside with life. Ana Amado and Andrés Patiño have travelled all over Spain for several years, capturing in their photos the landscapes, lost corners, customs, accents and the immense importance of agriculture and the rural environment. And, as they themselves state, "the architectures will remain standing at best, but those who first arrived, saw, built and worked hard are disappearing".

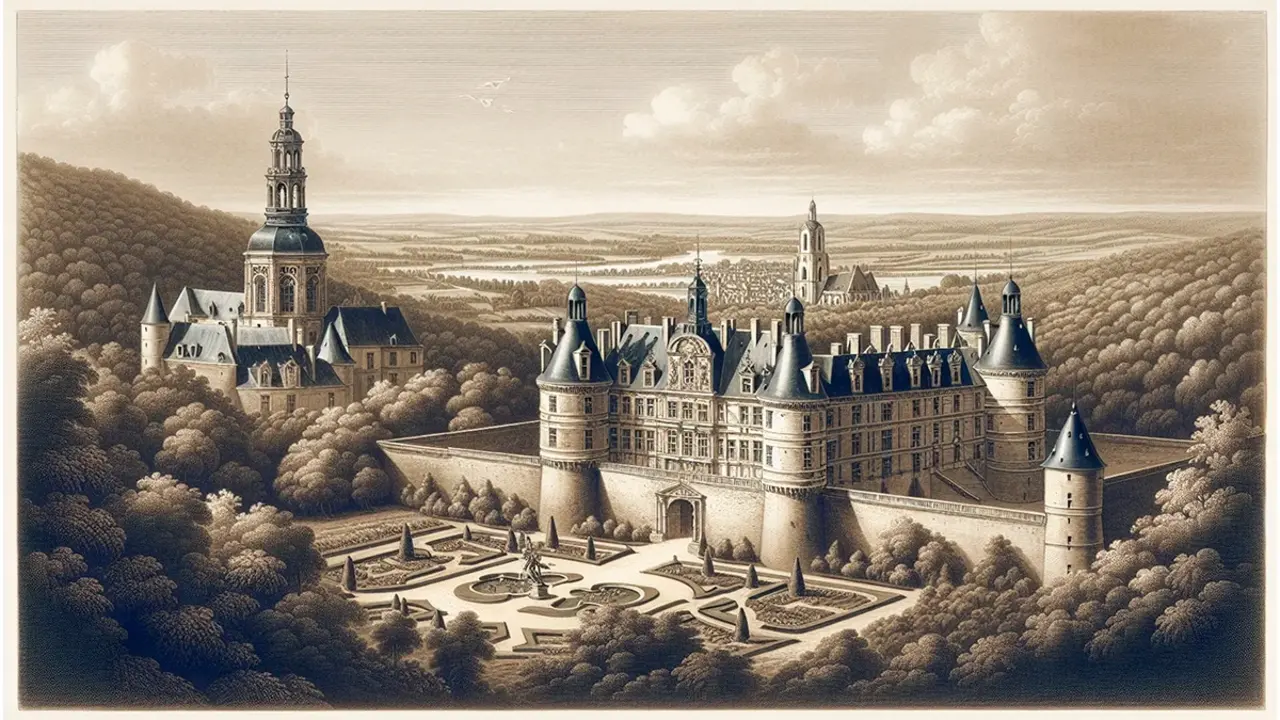

It was a project undertaken by the Instituto Nacional de Colonización (INC), created in October 1939, just after the end of the Civil War, and which would extend its activity until 1973. It took up both the regenerationist aspirations of the 19th century and the great principles of the Agrarian Reform of the Second Republic. Based on these pillars, the INC set itself the objectives of extending the area of arable land through the creation of irrigation systems, and of establishing, settling and controlling the peasant population in those unpopulated territories, with the aim of preventing rural exodus and ensuring self-sufficient agricultural production for the whole country.

Little by little, new villages sprang up in those barren and desolate fields: Valfonda de Santa Ana, El Temple and San Jorge in Huesca, Sancho Abarca (Zaragoza), Gimenells (Lérida), Setefilla, El Priorato and Esquivel (Seville), Miraelrío and Llanos del Sotillo (Jaén), Algallarín (Córdoba), Arneiro Terra (Lugo) and so on up to the more than forty settlements to which a voluntary population of poor peasants, humble and often very large families were transferred, who felt that they could change their own rather dark horizons for the better.

To these contingents would be added the groups coming from the forced population movements arising from the flooding of villages caused by the construction of the reservoirs needed to provide water for the new irrigation systems. These evictions from their roots would provoke many confrontations and dramas, such as that of the men and women of the idyllic nine villages that disappeared under the waters of the Riaño reservoir in León.

The settlers and their families, after all, emigrants in their own country, thus embarked on a new life starting from scratch, with new everything - houses, gardens and plots of land - under a very favourable economic regime, but subject to systematic surveillance and inspection and very strict control. They had to build their new identity, creating strong bonds of solidarity among themselves, and they were able to establish their own festivities and rituals, which allowed them to forge new traditions on the white canvas of the villages they inhabited, with their modern, abstract and uniform architecture.

The planning and design of the new settlements contemplated together the establishment of residences, the provision of services and agricultural production. This planning was based on both economic and aesthetic motives. These actions, as they were not subject to urban scrutiny, which was more prone to criticism and fierce debate, were to become a fertile field of research and experimentation for young architects, many of whom acquired fame and renown from their early rural works: José Luis Fernández del Amo, Alejandro de la Sota, José Borobio, José Antonio Corrales, Antonio Fernández Alba or Fernando de Terán found in the colonisation villages a propitious environment to reflect on the identity of Spanish architecture in the search for a synthesis between rationality and vernacular architecture.

The exhibition also includes the photographic work of the American photojournalist W. Eugene Smith for Life magazine. His aim was to influence against any political attempt by the United States to establish agreements with Franco's dictatorship. To this end, he photographed the most miserable-looking villages and people and included them in his report "Spanish Village: It Lives in Ancient Poverty and Faith", published on 9 April 1951. Despite the enormous media coverage of that report, which contributed to deepening the black legend of the darkest Spain, Spain and the United States signed the Madrid Pacts in 1953, which brought Franco's regime out of its international isolation.

The exhibition, which awakens an enormous variety of feelings, memories, recollections and nostalgia in visitors, will remain open until mid-May.