The open wounds of the Indo-Pakistani partition

This August marks 77 years since the tragic partition of India into two states, whose borders were hastily drawn by the lawyer Cyril Radcliffe, who had never set foot in the territory, under the orders of Lord Louis Mountbatten, King George VI's cousin and until then viceroy of the so-called jewel in the British crown.

It was not an amicable separation. Two post-colonial conceptions clashed: that of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, who wanted India to be a single, unified nation, and that of the leader of the Muslim League, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who believed that Muslims would be increasingly disadvantaged without their own sovereign state. Only a year earlier, in 1946, Jinnah had already prophesied this by calling for a day of action: "Let us choose between a divided India or a destroyed India". That day of action would result in 4,000 dead and 10,000 wounded, foreshadowing the many clashes between the two communities.

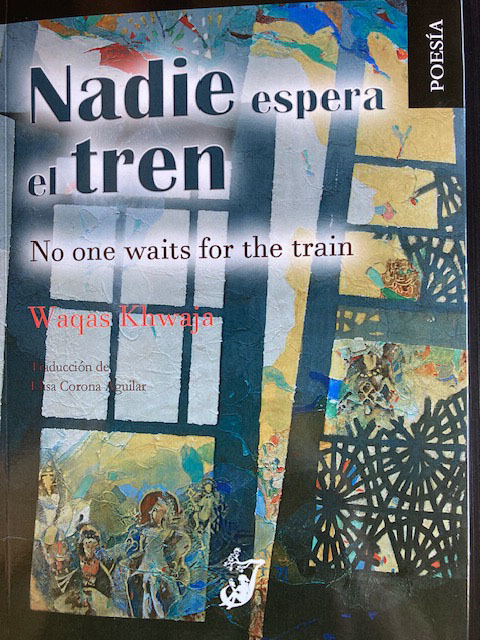

Waqas Khwaja, born in Lahore and recognised as one of Pakistan's greatest poets, author of numerous works, depicts in many of them the tragedy that was for no less than 15 to 18 million people the greatest migratory episode of humanity: millions of Muslims leaving their homeland of origin, home to their families and ancestors for hundreds or even thousands of years, to settle in a new and unknown territory for them, now called Pakistan. Likewise, millions of other Hindus, with similar personal and family histories behind them, were crossing the border in reverse to settle in the "right country". The Lalamusa railway station, where the Pakistani flag was first hoisted, would be the main hub of that forced migration, where hateful glances were exchanged, prior to the numerous aggressions that would take place in those moments of redesigning the British colonial legacy, and the four wars that both countries have fought since their independence, in a conflict that many consider permanent and irresolvable.

"The smell of death everywhere/ The smell of loss/ The deadly stench of betrayal/ Every moment of existence/ An affront to life/ And then it seems as if the whole city/ Poured into the streets/ And marvelled at the desolation/ That marks every face". Khwaja renders the images of that tragedy in sober, terse words, words that resurrect its fearful content in vivid images. He evokes the tragedy and violence of those times and manages to do so as lyrically as he does with the palpable sense of loss of the narrator who must leave his beloved Kashmir behind.

Waqas Khwaja, whose voluminous work always insists on the intersection and interconnectedness of different cultures, speaks several of Pakistan's seven languages, as well as having become a professor of English at Agnes Scott College in the United States, where he lives, and where he organises an annual public celebration of poetry as part of the international 100,000 Poets for Change project.

Pakistan's new ambassador to Spain, Zahoor Ahmed, the organiser of the evening with Khwaja, endorsed Professor Deepika Bahri's gloss on his poetry collection: "This is poetry with conscience, language with heart, intellect shining through emotions. With these poems, Khwaja has entered the darkness of Partition and extracted from its violent, festering core that which can make it bearable: the sharp balm of memory and its partial, but hopeful, promise of healing through painful attendances".

A pleasant surprise for the reader is this edition of "Nadie espera el tren" (Ed. Juglar, 267 pages), in which editor Francisco Javier González has composed the book with the original English-language poems on the even pages, facing the excellent Spanish translation by Elisa Corona Aguilar on the odd pages.