When Spain signed peace with the indigenous nations

"I don't know if life deserves to be lived, but the world certainly deserves to be travelled", José Tono Martínez states categorically in the prologue to his latest book, "La vez que firmamos la paz" (Ediciones Evohé, 119 pages).

For this poet, writer, essayist, social and cultural anthropologist and doctor of philosophy, history is made up of "itineraries", whose chroniclers laid the foundations and shaped history, especially the gigantic Spanish epic in America.

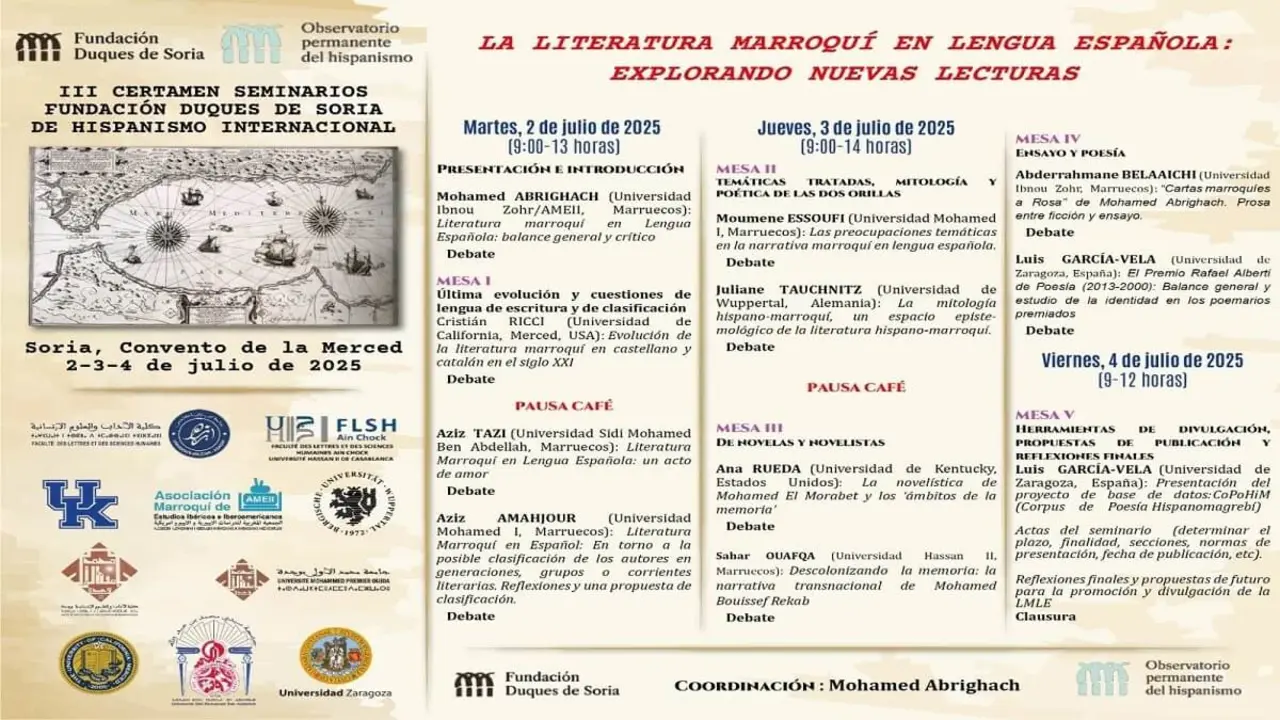

Between 1987 and 1993, the author was in Washington as an advisor to Rafael Mazarrasa, then president of the Spain'92 Foundation, representing Spain's Fifth Centenary Programme for North America.

Despite such a bombastic name, José Tono acknowledges that they did not officially represent the Kingdom of Spain, but also that "we knew that many of those who had started all that, five hundred years ago, had not represented it either. From the beginning, from before the very Capitulaciones de Santa Fe, the American business had been a story of biased interpretations, of misunderstandings that were intended, sometimes unwanted". He affirms that there was only one true and innocent representative, the first one, and it went badly, since in reality Admiral Christopher Columbus had powers for something else, for other commercial and diplomatic business that had to do with China and the Orient, but not for what he did. And, moreover, with bad luck or a bad head, as historians today agree that he was a terrible administrator.

The headquarters of the aforementioned Foundation was in Washington D.C., in former Indian territory, from where Mazarrasa and Tono himself had travelled the four years prior to 1992 through the immense country that is the United States, "setting in motion all those “things” that were expected of us: exhibitions, academic forums, magazines, cultural and educational programmes that didn't have to embarrass us and, of course, "we had tried to sell trinkets to the Americans and they, in turn, had tried to take all the money sent to us by the Crown; and even more, that in this business, and at home, the gringos are as implacable as they are cunning when it comes to leaving you penniless. At the poker table of negotiations, they almost always win. And the truth is that once they had taken everything from us, once they knew there was nothing more in the saddlebag, then they helped us", when Madrid had already abandoned them to their fate, behaving not unlike “those hypocritical and aloof officials of the old Councils of the Indies”.

But, by one of the many coincidences of fate, the Spain'92 Foundation, and its fleeced pockets, fell into the hands of the direct management and organisation of the voyage to be covered in North America by the ships of the Fifth Centenary of the Discovery.

The exact replicas of the Pinta, the Niña and the Santa María arrived in America under the command of Commander Santiago Bolívar, causing astonishment, expectation and a transformation in the spirits of the coastal populations in whose ports the expedition docked. "I can swear," says the author, "that among the many thousands who climbed onto the bridge of the Santa María to have their photo taken and look out over the sacred enclosure, there were also thousands who believed they were standing before the "sancta sanctorum" of Christopher Columbus".

For months prior to 12 October 1992, the Indians and their hardened social and political organisations had been preparing for what was to be the culminating moment to expose their demands to the world, to air their protests as neglected native peoples. It was when Mazarrasa came to an agreement with the mayor of Baltimore to allow the Indians to "assault" the three caravels, which resulted in the hoisting of one of the Indian flags next to the admiral's flag. The Indian chiefs were thus justified in the eyes of their rank and file, while the flying of the native flag alongside that of Castile was tantamount to a total and sacred reconciliation.

This gesture was greeted with great displeasure by "the resentful people in the Ministry [of Foreign Affairs], who wanted to show that diplomacy, even sentimental diplomacy, must be done by professionals. And not two "condottieri di ventura" like we were".

To add to the displeasure of the Palace of Santa Cruz, Rafael Mazarrasa agreed to sign a Declaration of Respect for the Indigenous Nations and Cultures of the Western Hemisphere with some twenty leaders of Indian peoples. The event was held in the Windows of the World restaurant of the Twin Towers in New York, nine years before their destruction in the most audacious terrorist operation in history. A peace that hardly anyone in Spain knew about, apart from foreign ministry officials.

They were spared the withering dismissal and subsequent return to Spain, as happened to so many anonymous protagonists of the Spanish conquest and colonisation of America, by an editorial in the powerful The New York Times, which hailed the Spanish position, "considering our declaration of respect and recognition a milestone".

Instead of the gallows or the galley sentence, the protagonists of this story experienced the sequence of that unexpected editorial, followed in Madrid by surprise, complicit silence, congratulations and... oblivion.