Writers and artists under communism

"The sin of almost all leftists from 1933 onwards is that they have pretended to be anti-fascist without being anti-totalitarian," said George Orwell, whose deep communist convictions collapsed when he came into contact with Stalin's henchmen in the Spanish Civil War. This view was echoed by the Chilean Jorge Edwards, who said that "the left is still locked in the Chinese shoe of Manichaeism". Both categorical assertions, which, almost without nuance, are fully valid at this point in the 21st century, although the communism of that time is masked today under a multitude of different names.

"Writers and Artists under Communism", eloquently subtitled "Censorship, Repression and Death" (Arzalia Ediciones, 910 pages), is the latest monumental work by veteran journalist Manuel Florentín, a war correspondent in Yugoslavia and the Gulf, and author of historical and international political works in which he has balanced rigorous data with exhaustive documentation.

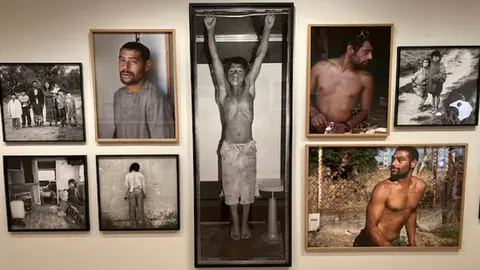

Now, in his latest book, he moves away from the political vision that usually pervades the usual stories about communism, to focus on the writings, experiences and dramatic personal vicissitudes of novelists, poets, playwrights, journalists, thinkers, scientists, musicians, painters, filmmakers, all creators who defended freedom of expression, democracy and human rights in countries that suffered under communist dictatorship, real socialism, often and sarcastically disguised as "popular democracy".

For this reason they suffered censorship, imprisonment, torture and death, both physical and the "literary death penalty", denounced by the Russian Evgeni Zamiatin, the pioneering author who inspired Orwell to write "1984", and who left us a terrible quote: "In other countries writers are admired, while in Russia their faces are smashed in".

Since Lenin's devastating rebuttal of Gorky: "Intellectuals, lackeys of capital, think they are the brains of the nation; in reality they are not the brains but the shit", communist or related regimes have exercised - and exercise - relentless surveillance and censorship against those who either are not enthusiastic enough in applauding the totalitarian rulers, or do not conform to the literary and artistic canon decreed formerly by the party, now by the so-called "woke" or "progre" dictatorship.

Critics of the system in communist countries paid with prison and their own lives for their criticism of the system or the dictator; nowadays, the practice is more one of cancellation, absolute ignorance of dissidents, who are closed to doors and opportunities in societies whose fundamental laws proclaim the equality of their people.

In his work, Manuel Florentín covers practically all the countries in which there were, or are, communist or similar regimes, with countless names and surnames, people whose existence is unknown to an immense part of humanity. But it also recalls the millions of anonymous, forgotten people who suffered the same repression.

Important, fascinating and even heartbreaking is how this book shows the behaviour observed in the West by the counterparts of those who were repressed. How they denied, qualified and justified human rights violations in communist countries in order "not to undermine the revolutionary cause". And how they criticised and ignored those who denounced such unsupportive and unsupportive behaviour.

There are the cases of the Nobel Literature Laureates Camus, Milosz or Vargas Llosa, Orwell, Koestler, Cabrera Infante and Victor Serge, among so many others. And how the party severely reprimanded artists, whether members or sympathisers, such as the universal Pablo Picasso, at the slightest deviation from the official line.

The book opens with a deluxe preface by Antonio Elorza, who had first-hand knowledge of the rigour, discipline and even physical aggression that were the order of the day within the Communist Party of Spain towards anyone who dared to question the dictates of its secretary general, at the time Santiago Carrillo.

It also highlights the "curious asymmetry" with which Nazism and Communism are judged in the West, both of which have also been condemned by the European Parliament. When I lived in Lyon as a co-founder of the European television channel Euronews, there was a music-festive celebration venue called KGB. No one thought much of the little name, although the British historian Timothy Garton Ash wonders whether anyone could imagine giving such a place the Gestapo label.

Florentín also points out that names like Dachau, Buchenwald or Auschwitz are etched in everyone's memory, but that very few will remember or even perhaps have never heard of Vorkutá, Kolimá Solovetskí or Magadán.