The threat of China's deep-sea fishing fleet

We begin our journey in this space by addressing a problem that is little known and virtually absent from both international debate and the mainstream media.

There is no doubt that China will be one of the major players on the geopolitical stage in the coming decades, and probably in the coming centuries. An interesting aspect of China's approach is its continued reluctance to use its military power beyond its natural sphere of influence. Even within this sphere, the projection of its enormous muscle is very limited compared to the approach taken by other powers.

The importance of the Chinese fishing fleet

However, this does not mean that Beijing does not use other tools to exert influence where it considers it necessary or beneficial to its interests, and its modus operandi takes countless forms. One of these is the use of its deep-sea fishing fleet, a key element in the Chinese economy and in sustaining its huge population.

The People's Republic of China's fishing fleet represents an unparalleled maritime capacity on the global stage, far exceeding the capabilities of all other nations combined. This floating power not only seeks economic benefits, but also operates as a crucial vector for the projection of state power in the ‘grey zone’.

Estimates place the total number of Chinese fishing vessels at more than 16,000, a truly exorbitant figure. This magnitude makes it the main driver of deep-sea fishing worldwide. The US Department of Defence has repeatedly pointed out the importance of this fleet in the context of a broader Chinese strategy, highlighting the need to update threat monitoring and management measures in view of its possible use in dangerous situations.

While security professionals and naval strategists develop theories about the possible use of China's astonishing number of fishing vessels, their main purpose is to supply food to an increasingly prosperous Chinese population with a growing need for protein. The changing diet of China's 1.4 billion citizens and the corresponding increase in imports have dramatically changed global protein markets over the past decade.

Food in China

Coinciding with repeated failures in agriculture and livestock farming, caused by livestock diseases, water pollution and poor management of already scarce farmland, China has experienced a remarkable and growing increase in demand for meat for human consumption. As a result, China's domestic production has been so overwhelmed by demand that the country has unusually exposed itself to increasing trade dependency, such as the 2020 Phase One trade agreement with the United States.

Although protein imports may seem like a low-risk necessity from the perspective of Western countries, from Beijing's perspective, steeped in Maoist philosophy that advocates self-sufficiency in food production, they represent a serious problem.

Overfishing and the fishing market

The significant and growing demand for protein has led the Chinese fishing fleet to aggressively overfish all regional fishing grounds, earning China the top spot as the world's worst fishing offender. While its fleet of more than 16,000 deep-sea vessels appears to be an interesting asset for military analysts to study, economists may consider the need for a fleet that travels so far as a built-in liability. Requiring such a large deep-sea fleet suggests that China may be experiencing a much greater collapse of fish stocks in nearby seas than is currently known. And that problem not only affects China, but will have a clear impact on the entire region, adding further reasons for tension to those that already exist.

After devastating its own fishing grounds, Beijing has extended its practice of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing to Africa, South America, Oceania and, most recently, the Arctic region. Open-source reports from non-governmental organisations and government agencies extensively document these illegal practices by China in West Africa in particular. Many of the countries affected by these practices are associated with the Belt and Road Initiative, which makes perfect sense, but they are quietly facing an existential threat from overfishing due to their critical nutritional and economic dependencies. The challenges of overfishing pose enormous problems, but they are not immediately obvious. The effects often extend into the legitimate economy and destabilise a number of factors such as unemployment, tax revenues and many others. Generally, in regions already strained by other factors such as underdevelopment, lack of investment in infrastructure, low levels of education, ethnic and tribal problems, and the effects of illegal fishing in their fishing grounds, which they tend to exploit in a traditional and low-intensity manner, this ends up exacerbating the existing precarious situation and causing new conflicts, thus creating an impossible spiral.

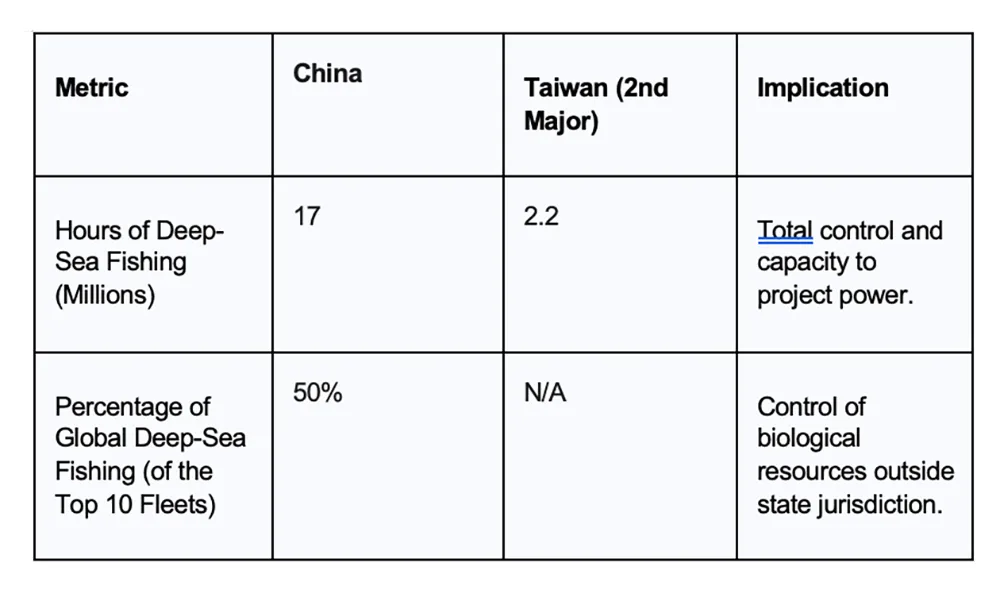

The dominance of this fleet can be quantified rigorously. China's fishing effort far exceeds the combined total of the next nine largest fishing fleets in the world. China, together with Taiwan, Japan, Spain and South Korea, is part of the group that accounts for more than 85% of deep-sea fishing, half of which (50%) is carried out by Chinese vessels alone.

The attached table summarises the operational scale of the deep-sea fishing fleet compared to its closest competitors:

To understand the threat, it is essential to define the components of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing, as each element of Chinese activity exploits a different weakness in the international regulatory framework.

Illegal fishing (I) refers to activities carried out by vessels flying the flag of a State without permission from the competent authorities, or in contravention of their laws. Undeclared fishing (UD) involves operations carried out in the area of competence of a regional fisheries management organisation (RFMO) that have not been declared, or have been declared inaccurately, in breach of reporting procedures. Finally, Unregulated Fishing (URF) refers to fishing in areas where there are no applicable management or conservation measures, or where the flag State is not a member of the relevant RFMO.

In the Chinese context, the dominant strategy is focused on maximising Undeclared and Unregulated practices on the high seas, in areas adjacent to the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of third countries. This approach allows for the intensive exploitation of stocks that move within the boundaries of these areas in an opaque manner, where the monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) capabilities of coastal countries are difficult to exercise on a sustained basis.

The massive reach and capacity of the Chinese fleet to operate continuously thousands of kilometres from its home ports would not be possible without systematic state support. Chinese government subsidies for ship construction and maintenance are the mechanism that allows operations to remain economically viable despite long distances and resource depletion.

These subsidies serve a key strategic function: they distort global fisheries markets, allowing Chinese operators to maintain an unfair competitive advantage that displaces local and artisanal fleets. Furthermore, subsidies facilitate a cycle of exploitation and geographical displacement. Once fleets have depleted the seas near China, capital, liquidity, and a favourable regulatory environment facilitate the expansion of the fleet to distant regions such as Africa and Oceania. This mechanism transfers the environmental and economic costs of overexploitation to more vulnerable foreign nations, demonstrating that China's distant-water fishing fleet is an integral component of Beijing's foreign policy, capable of projecting its maritime influence without directly resorting to military assets.

From a security perspective, the development of this disproportionate deep-sea fishing fleet has significant strategic value. The US Department of Defence has contextualised the fleet as part of a broader Chinese strategy. It has been noted that this experienced force could be ‘useful and decisive in a large and protracted maritime conflict.’ Because we must not forget that, in the Asia-Pacific region, the main theatre of a hypothetical conflict will be maritime domain.

This suggests a crucial role for the Chinese Maritime Militia (CMM). The constant presence of thousands of fishing vessels in international waters, and close to the maritime borders of other countries, establishes a de facto presence of the Chinese state. These vessels can perform reconnaissance, signals intelligence, and act as support or cover for naval and coast guard assets, contributing to the projection of state presence without triggering an escalating military response, which defines coercion in the grey zone.