GMV technology to catch satellites before they become space junk

- Grab, drag, boost, de-orbit, de-orbit and burn

- Preventing entire satellites from becoming large pieces of space debris

GMV has been able to respond to the trust placed in it by the European Space Agency (ESA) and has made a technology a reality that is capable of removing broken or out-of-service satellites from space and thus preventing the multiplication of space debris.

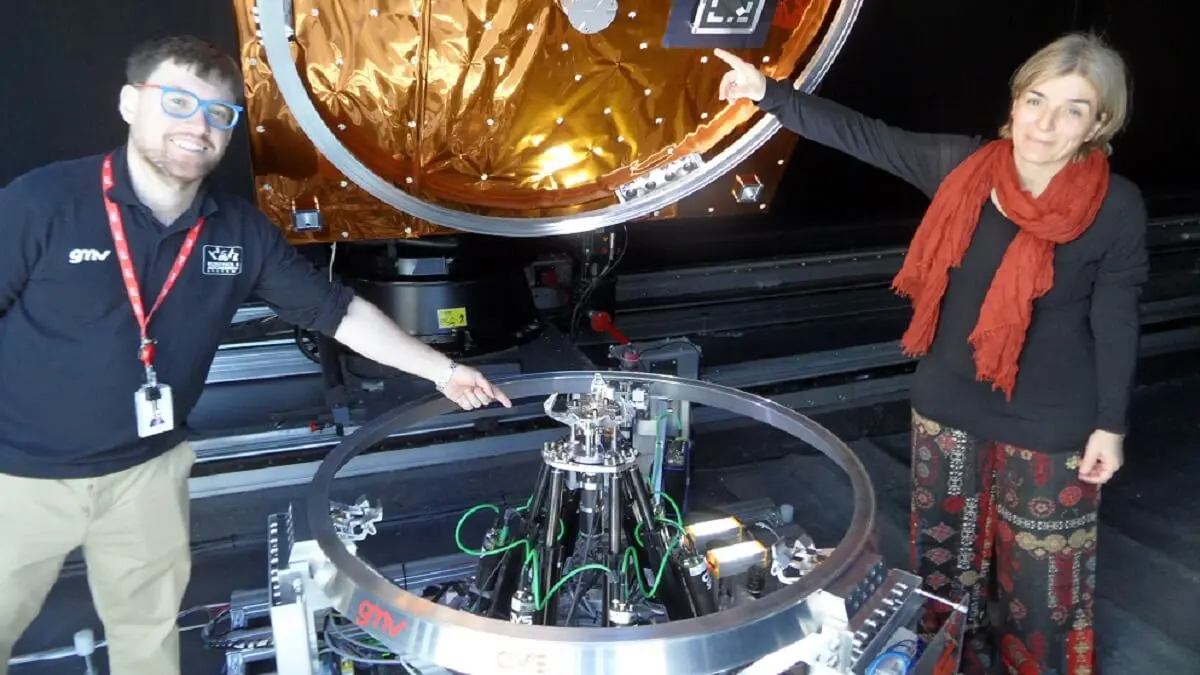

It is the work of a team of GMV engineers, in collaboration with technicians from the Spanish company AVS, under the orders of Fernando Gandía, head of the Robotics and Embedded Autonomy department.

Under the guidance of the director of GMV's Science and Exploration flight segment, Mariella Graziano, the Spanish technology company has designed and built a simple and ingenious system for trapping satellites of the European Space Agency (ESA) and preventing them from becoming debris that travels uncontrolled around the Earth.

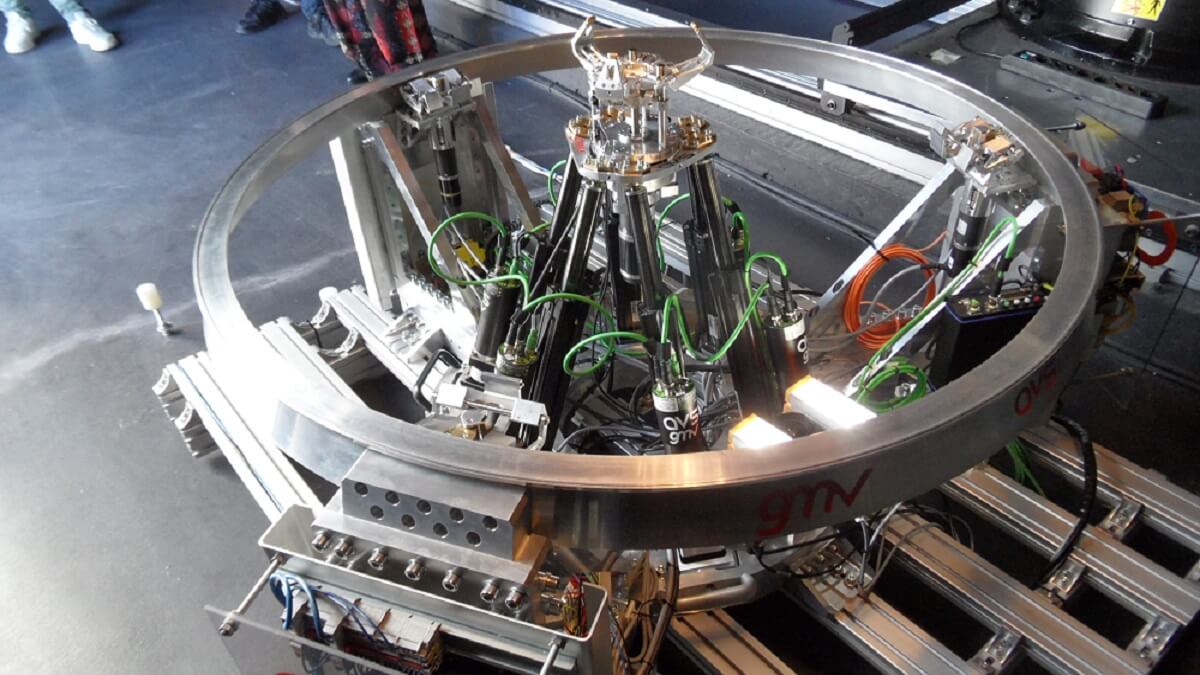

The system they have devised and manufactured consists of two devices called CAT and MICE, which allude to the mission for which they have been created, similar to that of the cat that catches mice. For this reason, the system also incorporates tiny cameras and tiny proximity sensors, similar to the sensitivity of the whiskers and the visual acuity of the eyes of rodents and cats.

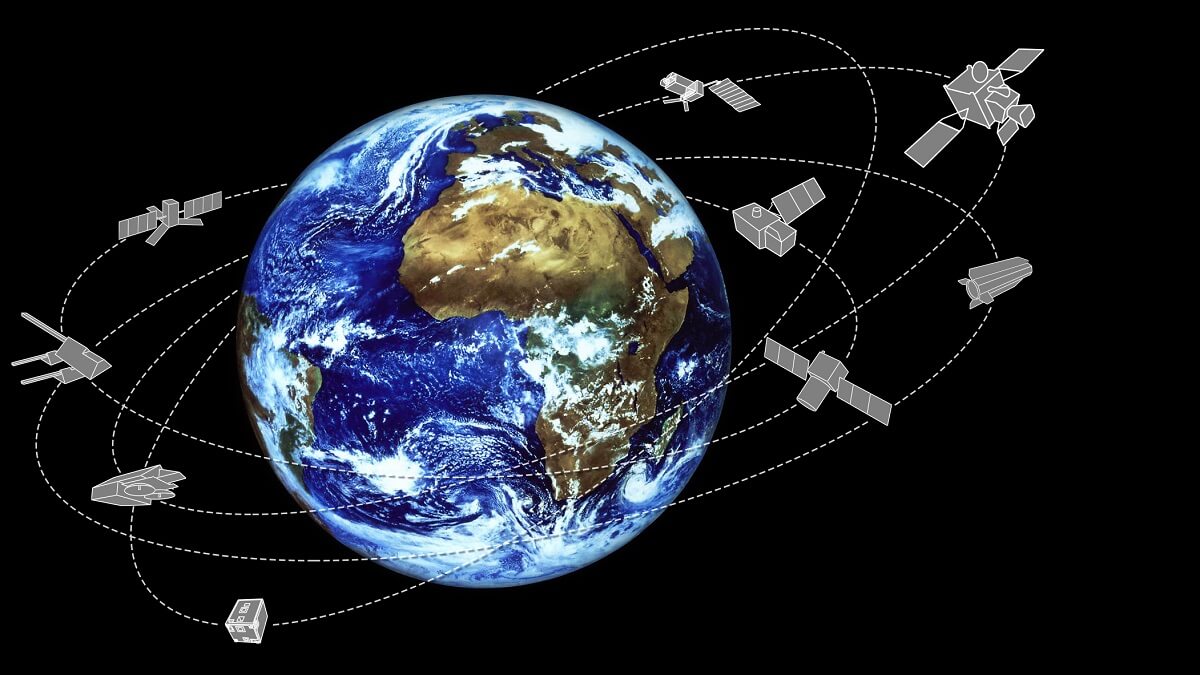

To fulfil the task, ESA has determined that MICE will be installed on the underside of the second-generation Sentinel satellites of Europe's Copernicus constellation. They will be launched into orbit from the end of 2028 and will be dedicated to diagnosing the state of the atmosphere, surface and seas, as well as providing data and imagery to address security risks and emergency situations.

Grab, drag, boost, de-orbit, de-orbit and burn

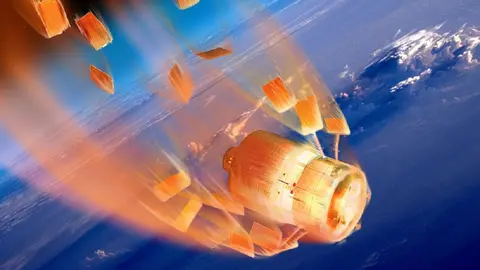

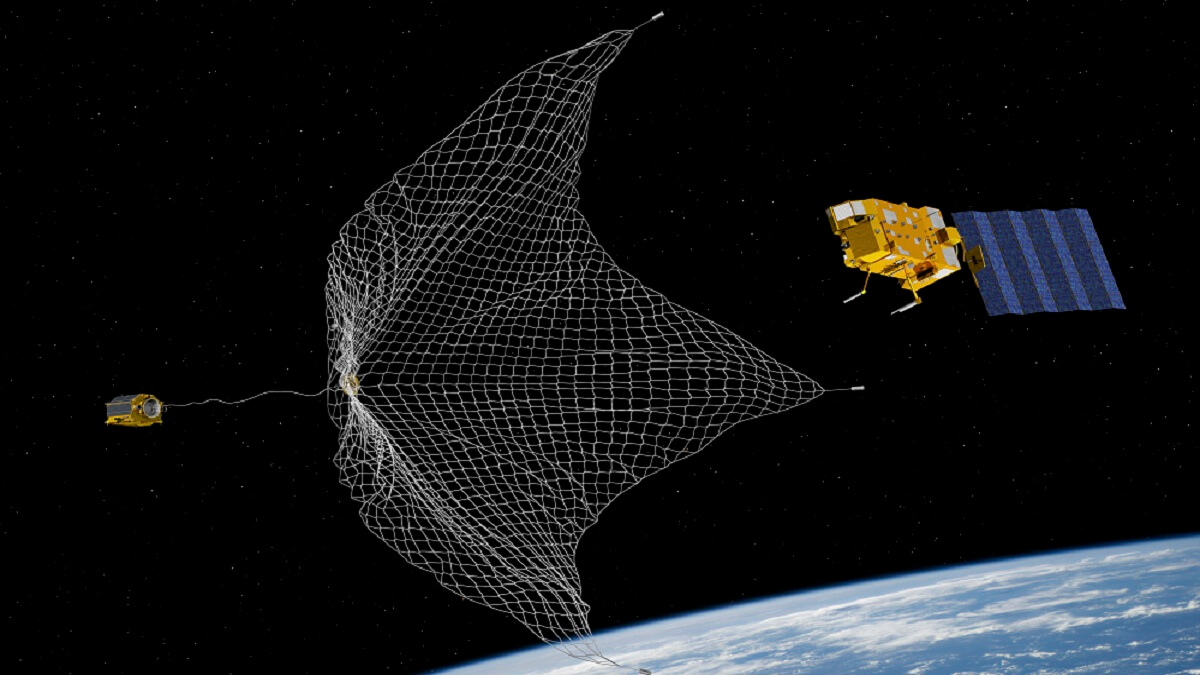

But once the mission that took them into space has been accomplished, or in the event that they suffer an anomaly that takes them out of service prematurely, the European agency wants them to be de-orbited and destroyed with full safety guarantees before they have been inoperative for five years.

And that is where the CAT device comes in, the one that does the job of the hunter. It is supported by six arms that move and position a kind of claw with three fingers. Its function is to ‘firmly grasp the disused satellite that is to be eliminated, drag it and propel it towards the Earth, causing it to burn up completely as it penetrates the upper layers of the atmosphere,’ says Andrés Rodríguez Reina, head of GMV's Space Robotics Engineering department.

Italian Mariella Graziano, an aerospace engineer from Rome's prestigious La Sapienza University with 25 years' experience at GMV, revealed that CAT “has already passed all the tests on Earth and only needs to be tested on board a satellite”. He stresses that GMV's system ‘is more flexible, simpler, safer and cheaper than a robotic arm’.

Graziano stresses that CAT is expected to be put into orbit ‘at the end of 2027 or early 2028, to fulfil a flight demonstration mission at an approximate cost of 50 million euros’. The satellite with CAT on board is designed to perform its task a minimum of three times and then disintegrate in the atmosphere. But Graziano is confident that it can de-orbit ‘between five and ten satellites’.

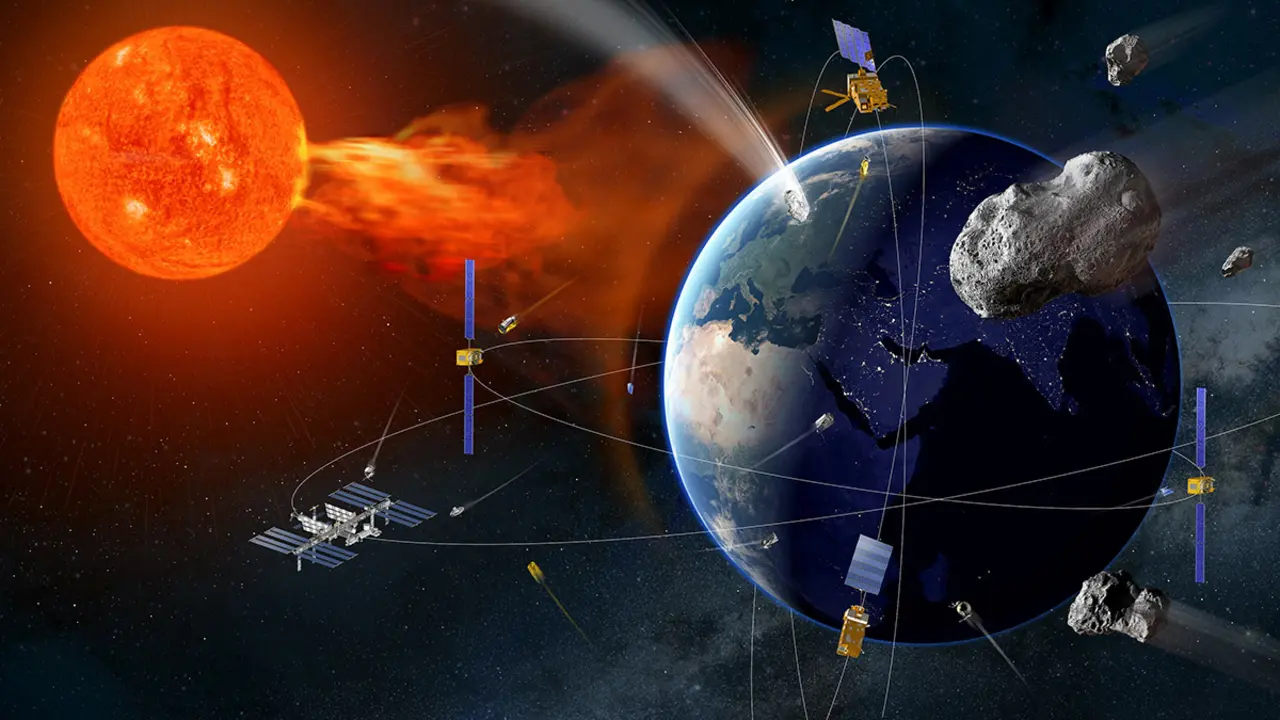

What ESA is trying to achieve through MICE and CAT is to preserve the sustainability of the ecosystem around the Earth and help make it possible to deploy constellations of hundreds or even thousands of new satellites with as little risk of collisions as possible. GMV's data show that around 11,500 satellites are still in orbit and more than 9,000 are still in service.

Preventing entire satellites from becoming large pieces of space debris

GMV's system to prevent entire satellites that are out of service from becoming debris swarming uncontrollably around the Earth runs in parallel with the Zero Debris Charter, sponsored by ESA in collaboration with agencies, industries, operators and even insurance companies.

It is a non-binding agreement that aims to end the generation of new rocket and satellite debris by 2030. It calls on companies and agencies that own satellites to dispose of them at the end of their lives without leaving debris, both those in low and medium earth orbit and those in geostationary orbit at 36,000 kilometres.

The Zero Debris draft was released at the ESA ministerial summit held in Seville in early November 2023. The space agencies or their equivalents in Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden, Slovakia, Austria, Belgium and the United Kingdom have recently joined the initiative. A second round of signatures is possible during ILA Berlin, which will be held in the German capital from 5 to 9 June.

The Spanish Space Agency and the Ministry of Science are committed to the sustainability of space and the reduction of debris parked in orbit. But official sources understand that the reasonable thing to do is to ‘wait for Brussels to pass the European Space Law and thus avoid possible dysfunctions between the two documents’. The Spanish criterion is shared by other agencies, for example, those of France (CNES) and Italy (ASI). With the European elections scheduled for 9 June, the law will not see the light of day until the last quarter of the year.

According to ESA's Space Security programme coordinator, Frenchman Quentin Verspieren, the Zero Debris Charter is an expression of Europe's ‘unwavering commitment to become a world leader in space debris mitigation and removal’. The Charter, like GMV's MICE/CAT system and the future European Space Act, seeks to encourage action by the global space community to make outer space activities sustainable in all respects.