Armenia still demands justice and international recognition

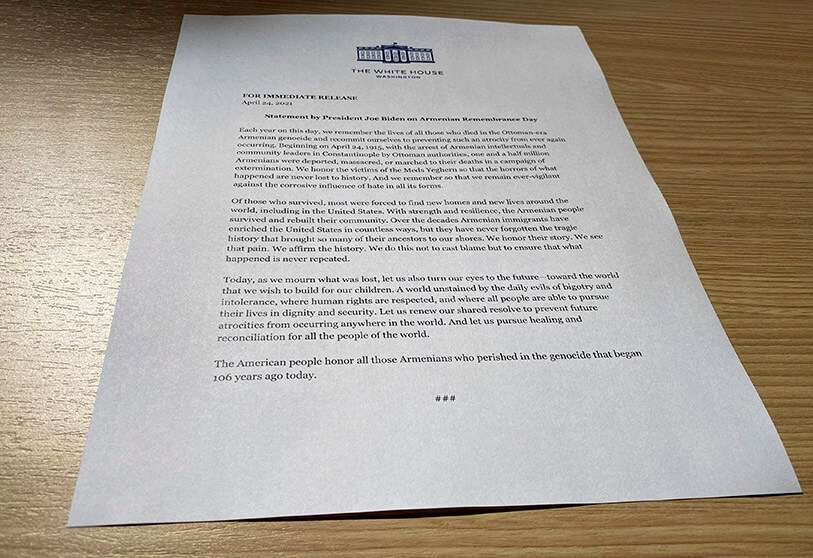

This weekend marked the commemoration of the Armenian genocide, considered the first genocide of the 20th century. Coinciding with the anniversary of this tragedy, US President Joe Biden has decided to officially recognise the massacres perpetrated against the Armenian population between 1915 and 1923 in the Ottoman Empire as genocide. An estimated 1.5 million people were killed in a process of ethnic cleansing against the Armenians.

The US government's decision has put the spotlight back on this event which, despite its historical relevance and the weight it still carries in Armenian society, has not been recognised by the international community as a whole. In addition to not recognising it, there are countries such as Turkey and Azerbaijan that still deny it. There is even one state that has not even recognised Armenia as a country. Pakistan, as a "form of solidarity" with Baku over its conflicts with Yerevan, does not consider Armenia a nation.

The Armenian population was part of the Ottoman Empire for centuries, just like the Greeks or the Assyrians. Two communities that share a common history with the Armenians, as both suffered mass killings and deportations at the hands of the Young Turks organisation during the same period of time. Armenians in the Ottoman Empire did not enjoy the same rights as the Turkish population, so from the 1890s onwards they began protesting for equality. Four years later, with the aim of suppressing the demonstrations, the so-called "Hamidian massacres" began, the main precursor to the genocide. These systematic massacres would last until 1896. They are named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ordered the killings.

The 1909 massacre of Adana, a city in the south of the country in which between 15,000 and 30,000 Armenians were tortured and killed, is also worth mentioning.

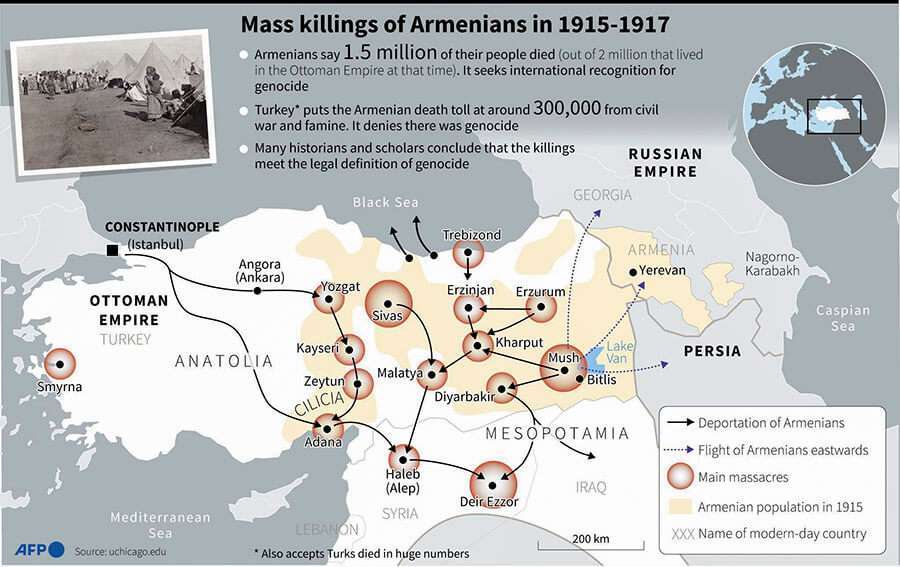

From 1914 onwards, the Ottoman authorities began a smear campaign against the Armenians, whom they considered "a threat to national security". Soon after, the first mass killings began in small Armenian villages, where the Ottoman forces met with little resistance.

The Armenian genocide began in the context of World War I, after the Ottoman defeat by the Russian Empire at the Battle of Sarikamish in January 1915. From this moment on, the Young Turks, who did not recognise their own failure, began to blame the Armenians and accuse them of conspiring against the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Armenian and other non-Muslim soldiers were removed from the army and killed, becoming the first victims of the genocide.

On April 24 that year, Talat Basha, a member of the Young Turks and one of those directly responsible for the genocide, ordered the arrest of 250 Armenian intellectuals. This is the date chosen to commemorate the genocide as it is considered that the arrest of these intellectuals marked the beginning of the mass murder of the Armenian population.

A month after the arrests, the deportations began. On 29 May 1915, the "Temporary Deportation Law" was passed, giving the Ottoman government the right to deport anyone considered a threat to the nation. This is when the great tragedy of the Armenian people really begins, a tragedy unjustly treated by an international community unaware of what it still means for the Armenian identity. Descendants of survivors who have to endure how many countries have still not recognised the suffering their relatives went through.

Thousands of Armenians were transported to concentration camps in the Syrian desert, although many died on so-called "death marches" due to thirst, hunger or exhaustion. Those who made it there alive had to face inhumane conditions, with a lack of food and water. They were also victims of murder, torture and rape.

The New York Times was one of the first media outlets to report on the massacres. In 1915, it published several articles explaining the events, describing them as a "racial extermination planned and organised by the government". In August of that year it published a story reporting that "one million Armenians were killed or exiled". The US newspaper reported testimonies claiming to have found hundreds of bodies and bones in the camps in Anatolia. The conditions in which the survivors were arriving in Syrian cities were also described as resembling "living skeletons".

106 years on

US recognition gives hope to a people still seeking justice and international support. Only around thirty countries recognise the Armenian genocide. Many states do not do so because of the consequences for relations with Turkey, as was the case for years in Washington. Ronald Reagan was the first US president to speak of the Armenian genocide, but he did not officially recognise it for fear of Turkish reprisals. Similarly, Barack Obama was willing to take the historic step but was conditioned by Turkey, a key NATO ally.

The large Armenian community in the United States celebrated Biden's decision while commemorating the anniversary of the genocide. Between the joy at Biden's remarks and the emotion of remembering family members who suffered the genocide, the Armenian people feel a little more supported by international society.

Armenian activists in the US have thanked the government for its historic decision, as well as standing up to Turkey. “With this recognition today, the United States has said in no uncertain terms that it will no longer allow human rights to be treated as a commodity that can be bargained over with Turkey,” said Alex Galitsky, communications director for the Armenian National Committee of America’s Western region. Galitsky also points out that this recognition is "long overdue".

"This statement by President Biden gives us hope that our cause can still continue," says Nora Hovsepian, chairwoman of the Armenian National Committee and a descendant of genocide survivors. However, they stress that this is not all, that their struggle will continue. This decision is only a fundamental step towards achieving the justice and international recognition they have been longing for.