Disinformation: China takes the road opened by Russia

"Disinformation" is one of the words that have been at the forefront of geopolitics over the last decade. Sometimes it is a rather fickle concept, since it is not clearly defined and is therefore used to designate realities in an erroneous way. In short, disinformation as a strategy consists of the distribution of lies disguised as truthful information to create confusion and mistrust in broad sectors of the population.

Despite the fact that this practice is as old as war itself, the situation of hyperconnectivity in today's world has facilitated its implementation, above all, through the social networks of the Internet. In the last decade, Russia has been the international actor that has made the greatest effort in the design and application of this type of campaign, whose respective objectives, in general terms, have been to undermine citizens' confidence in the political systems of representative democracy.

Examples are numerous. The strategy deployed by the Kremlin in the invasion of South Ossetia in 2008 is usually the first. The war against Georgia served as a testing ground for the implementation of mechanisms for the massive manipulation of public opinion. Since then, a similar mechanism was seen again in the Donbas war in Ukraine, where military action on the ground was combined with the use of technological means and so-called information operations or 'info-ops'.

Recently, the disinformation media at the service of the Kremlin, already consolidated as a functional and well-organized structure, launched operations to influence several appointments with the ballot boxes in the United States and Western European countries.

The current coronavirus pandemic has provided a new opportunity to reactivate that machinery of hoaxes, speculation, rumours and half-truths created in the spheres of power of Russia; a so well-oiled structure that, on this occasion, has not even required activation by higher instances of the Kremlin, but, in the opinion of The Elcano Royal Institute researcher Mira Milosevich, has been able to adapt to the circumstances and take advantage of the context.

Milosevich was one of the participants in a virtual meeting sponsored by the Spanish think tank itself at the end of April, which dealt precisely with the issue of disinformation in the context of the current crisis. The round table was moderated by Charles Powell, Director of Elcano, and the speakers included the researcher Mario Esteban; Ivana Karaskova, researcher on China and project coordinator of the Czech Republic's Association for International Affairs (AMO); and Alina Polyakova, President of the Centre for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) in Washington.

China: Does the apprentice surpass the master?

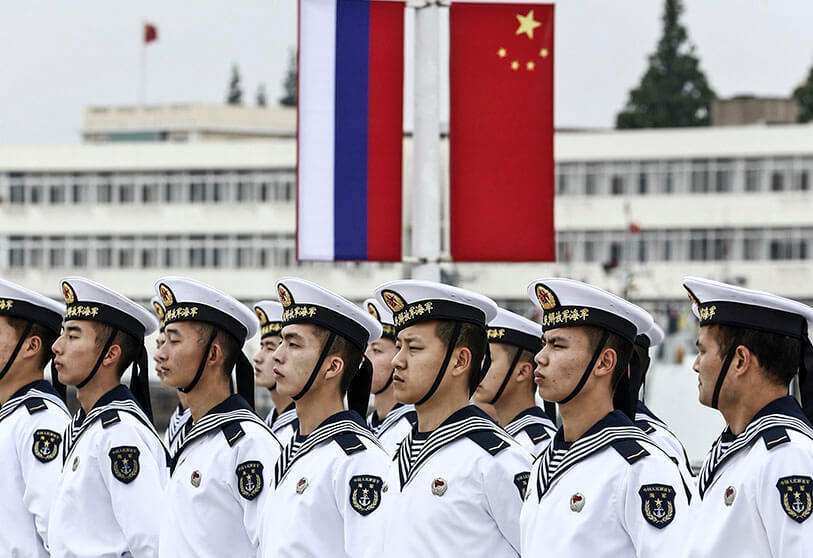

As expected, Russia is one of the two central actors in the debate. The other big name brought up was that of China; a geopolitical giant which, until now, had not lavished itself on the execution of disinformation campaigns, but which, in the current situation, is disqualifying itself as Moscow's leading pupil.

"Many of us wondered when China would put its enormous resources and capacities at the service of disinformation," reflects Polyakova. "Its actions regarding this issue are something we had never seen before".

Indeed, over the last few decades, China had already launched several campaigns to re-launch its image in relation to international public opinion. Ivana Karaskova acknowledges the widespread presence of such campaigns of what is called "public diplomacy". These actions were not intended to confuse public opinion, but, in a way, to give the Beijing regime a facelift.

Even in this field, there has been a rather remarkable change in strategy in the wake of the pandemic: from a defensive position to a markedly offensive one. This has been the case, for example, in the Eastern European region, where the think-tank headed by Karaskova is conducting its research. There has been a much greater penetration of Chinese-funded media since the outbreak of the coronavirus.

The wave of disinformation coming from Beijing is indeed a novel approach that has come hand in hand with the Wuhan-originated pandemic. One of the most notorious examples has been the hoax that the virus was originally manufactured in laboratories in the United States and released on Chinese territory to weaken the Chinese government. This theory -which science has proved to be false- was promoted from high levels of Chinese power and went around the world. It also arrived in Spain, where the Embassy and the Consulate contributed to spread it, as documented by the sinologist Esteban.

Thus, inspired by previous Russian experiences, China has been implementing a strategy that combines disinformation and public diplomacy. According to Polyakova, attempts at disinformation, as with previous Kremlin campaigns, have been used to achieve short-term objectives - escaping the storm during the pandemic, in this case - while public diplomacy is more oriented towards shaping the country's image in the future.

China, therefore, has been playing with high lights, and that is something that should be of concern, warns the Washington-based researcher. "Until now, [China] has been relatively benign. However, its long-term strategy has a much more corrosive effect. What in the past has been seen as simply a positive message is more than 'soft power'; there is a much greater intention to censor information across the globe. COVID-19 has left this kind of activity in the open," Polyakova said.

Polyakova points out that, despite the fact that it is still a little studied reality, it is revealing to observe the image that China is projected in the Russian media and vice versa. In both cases, praise prevails over criticism, a feeling that is subsequently amplified by social networks.

For this reason, at least as far as disinformation is concerned, it is worth asking whether it really matters to distinguish between Moscow and Beijing as sources of these campaigns. The governments of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping already share much of the malicious content they promote, as well as tactics to expand their influence, as director Powell points out. The objectives, at least in the short term, are similar.

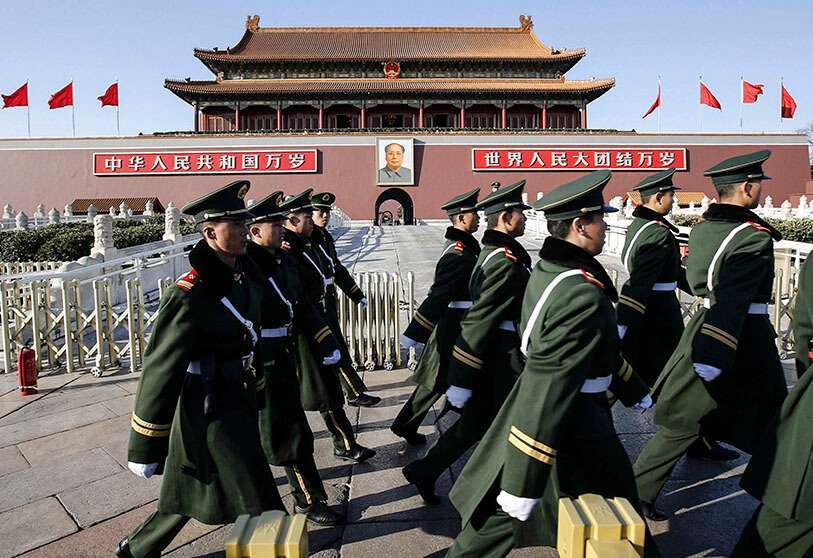

Basically, it is a matter of undermining as much as possible the perception that citizens have of democratic systems. Should the image held by millions of people of this type of political system move from acceptance to scepticism or, directly, to rejection, it is more likely that a collective feeling will be generated in favour of models that, although formally democratic, are based on strong leadership and greater social control, as is the case in both China and Russia; a change in political culture that would be highly beneficial for this tandem to expand its geopolitical dominance even further.

In this way, the phenomenon of disinformation transcends not only the coronavirus crisis, but also the examples of previous campaigns. The fact that they are used repeatedly "every time the others have problems", in Powell's words, raises the question of whether this is a long-term effort. In Moscow, it is more confined to the mere induction of confusion; in Beijing, it is mixed with a public diplomacy effort that, on the whole, can be even more powerful.