Why does the Algerian state harbor such deep hostility toward Morocco?

- A Systemic Hostility Rooted in the Algerian Regime’s Crisis of Legitimacy

- Algeria’s Geostrategic Imagination: Between Confiscated Tindouf and a Fantasized Atlantic

- From Historical Falsification to State Indoctrination: Anti-Moroccan Hatred as the Regime’s Survival Matrix

- A Power in Search of Enemies: The Strategy of the Void

It is worth underscoring that this question continues to resurface persistently within diplomatic circles and international public opinion, as it puzzles seasoned observers of Maghreb and African dynamics. The Algerian state's enduring hostility toward Morocco goes far beyond the confines of a border dispute or a typical regional rivalry. It reflects a deeper logic of political legitimacy-building, in which Morocco, far more than just a neighboring country, has become the functional “other” through which the Algerian system defines itself by confrontation.

This systematic rejection is not grounded in a well-defined ideological clash or a rational strategic dispute. Rather, it reveals a strategy of internal evasion, an attempt to sidestep the failure of the national project, to delay the reconstruction of state institutions, and to avoid confronting a legitimacy frozen in the glorified memory of the war of independence.

Moreover, behind this question lies far more than a conventional geopolitical disagreement or a mere diplomatic divergence. At its core, this hostility exposes a structural imbalance between two divergent historical trajectories and two opposing models of state legitimacy. Morocco, anchored in a millennia-old monarchy, a clearly defined geopolitical centrality, and a forward-looking reformist vision under strategic royal leadership, embodies a form of adaptive stability that psychologically unsettles the Algerian regime. Deprived of a genuine unifying founding myth, Algeria’s leadership struggles to build a compelling national narrative, falling back instead on the rigid rhetoric of the independence war, which has ceased to serve as a foundation for a national project and has instead become an ideological shelter from the demands of the present.

A Systemic Hostility Rooted in the Algerian Regime’s Crisis of Legitimacy

In this symbolic deadlock, hostility toward Morocco functions as a surrogate for lost legitimacy. Lacking solid geopolitical levers, be it influence corridors, diversified strategic partnerships, or credible economic outreach, Algeria offsets its isolation through a compulsive posture of opposition toward its western neighbor. Unable to integrate into regional co-development dynamics, marginalized in major African and Atlantic initiatives, and trapped within a self-contained security apparatus, Algeria has turned conflict into a mode of existence and hostility into a pillar of national identity.

This stance, built on obstruction, victimhood, and the projection of threats, also reflects a deeper existential fear: the fear of being sidelined in the emerging map of regional powers. Morocco, through its deliberate choices, economic openness, multidimensional diplomacy, and strategic anchoring in both Africa and the Atlantic, embodies a contrasting model that highlights the stagnation of the Algerian regime. This contrast has become intolerable for a military elite locked into a logic of authoritarian control and regime preservation.

This rivalry is also deeply rooted in longstanding geostrategic concerns and unresolved historical frustrations, which partly explain Algeria’s fixation on the Moroccan Sahara.

Indeed, from both a historical and strategic standpoint, at regional and continental levels, two key motivations underlie Algeria’s stance on the Moroccan Sahara. First, as a landlocked country hemmed into a geopolitically constrained Mediterranean, sealed off at the Strait of Gibraltar, Algeria has long sought strategic access to the Atlantic Ocean. Lacking any natural outlet to this vital maritime space, essential for global trade and strategic projection, Algeria fabricated the fiction of a client "Sahrawi state," whose artificial creation would serve as a geopolitical proxy, granting Algiers a backdoor to the Atlantic and circumventing established norms of territorial sovereignty. This was never an altruistic gesture or genuine support for self-determination; it was a calculated attempt to redraw the regional architecture in favor of an Algeria seeking functional expansion.

Algeria’s Geostrategic Imagination: Between Confiscated Tindouf and a Fantasized Atlantic

The Algerian state’s persistent hostility toward Morocco also draws from an unresolved flaw in the decolonization process: the issue of Morocco’s historically eastern territories amputated by French colonial administration in the early 20th century. Under the 1904 Franco-Spanish agreement, later enforced through unilateral colonial decrees, regions such as Touat, Saoura, Tidikelt, Gourara, and the Tindouf area were stripped from Moroccan sovereignty and arbitrarily attached to French Algeria.

Yet, contrary to Algeria’s rigid and selective interpretation of the uti possidetis juris principle, international law governing decolonization requires a flexible and equitable reading, one that respects preexisting sovereignties. The purpose of this principle is not to eternalize colonial injustice but to prevent post-independence chaos by preserving territorial units at the moment of independence, except where territories were severed in clear violation of international law. In Morocco’s case, this was not an amorphous territory handed down by imperial cartographers, but a centuries-old sovereign state whose borders were internationally recognized long before colonization.

On this point, the International Court of Justice itself, in multiple advisory opinions, most notably the 1975 ruling on the Moroccan Sahara and the East Timor case, clearly stated that uti possidetis juris cannot override the right of peoples to reclaim full sovereignty. Nor can it nullify prior international commitments or historically established facts. This principle is particularly relevant in Morocco’s case, where territorial claims are grounded in preexisting sovereignty and supported by duly ratified international treaties

This view is reinforced by Article VI of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514, adopted on December 14, 1960, which affirms: “If a state has been dismembered by colonialism, it has the right to recover its territorial integrity following decolonization.” In essence, the sovereignty of a recognized state cannot be permanently undermined by unilateral colonial amputations. This legal foundation disqualifies any attempt to elevate colonial frontiers into untouchable absolutes and opens the door for the legitimate restoration of territories, as in Morocco’s case.

Thus, this principle of territorial restitution is not a theoretical abstraction, it is grounded in documented historical continuity. Long before its colonial fragmentation by France and Spain, Morocco was a sovereign state whose borders were acknowledged in multiple international treaties. These include Moroccan-Spanish treaties of 1561, 1767, 1787, and 1799, and the 1867 Moroccan, American Treaty of Peace and Friendship, still in force today, which affirms recognition of Morocco’s territorial unity. Likewise, on March 13, 1895, a British-Moroccan agreement was reached following intense negotiations regarding British national Donald Mackenzie’s settlement at Cape Juby (north of Tarfaya). The article I of that agreement explicitly recognized Moroccan sovereignty over the entire southern region. This historical and legal continuity stands in stark contrast to Algeria’s current stance.

Today, by refusing any bilateral dialogue on these territories and treating colonial frontiers as sacrosanct, Algeria not only denies Morocco’s legitimate claims but paradoxically positions itself as the legal heir to the colonial order it claims to have resisted.

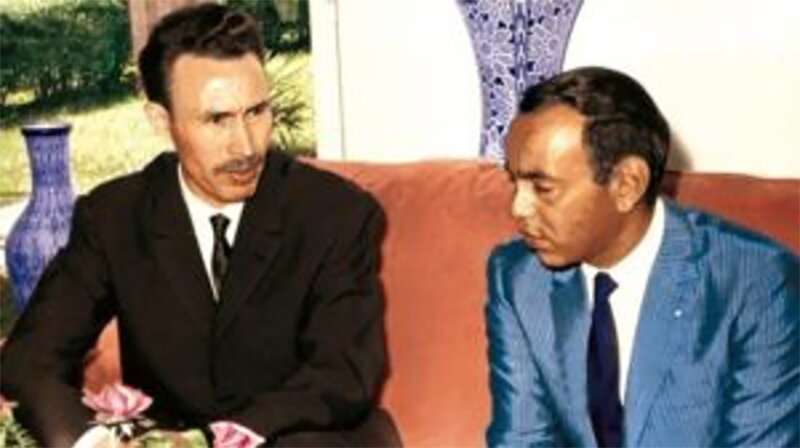

One critical, yet often overlooked, legal and diplomatic fact further illuminates the roots of the current tensions: On July 6, 1961, the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA), then led by Farhat Abbas and later Youssef Benkhedda, signed an explicit agreement with Morocco, committing both parties to address the issue of eastern border demarcation through bilateral negotiations once Algeria achieved independence. This commitment, rooted in good-neighborly relations and historical bonds between the two peoples, reflected an initial desire to resolve colonial-era territorial disputes peacefully.

However, this agreement was later unilaterally dismissed by the new Algerian regime following the political-military coup by Ben Bella and Boumediene against the GPRA. From its earliest days, this post-independence government adopted a rigid stance, sanctifying colonial boundaries and rejecting any discussion of historically Moroccan territories that had been annexed to Algeria under French rule. This reversal laid the groundwork for a longstanding Algerian doctrine of systematically rejecting border dialogue with Morocco, in open violation of prior commitments and the principle of good faith enshrined in international law.

This posture of denial is clearly reflected in Algeria’s obsession with the Moroccan Sahara. By artificially prolonging a long-outdated conflict, financing a separatist front with no real social base, and mobilizing its diplomatic channels to obstruct resolution efforts, the Algerian regime appears less interested in defending self-determination than in sustaining a controlled conflict vital to its own political survival. The Sahara issue thus becomes a kind of strategic mirror, its purpose is not to resolve a crisis but to delay the collapse of a system unable to reform from within.

Ultimately, modern history demonstrates that regimes anchored in perpetual hostility are doomed to strategic irrelevance and collapse. Algeria has already tested this doctrine in the 1970s and 1980s, attempting to extend its influence in sub-Saharan Africa by supporting armed movements and radical regimes, from the Polisario to Angola’s UNITA. These moves ended in diplomatic isolation and a loss of credibility. The 1963 Sand War, fought over poorly defined borders, ended in a quiet military setback. More recently, Algeria has sidelined itself from regional security structures by refusing to actively participate in coordinated frameworks like the G5 Sahel or global counterterrorism coalitions across the region.

While Morocco signed over 1,000 cooperation agreements with African countries in just a decade, Algeria remained entrenched in a sterile face-off with a neighbor that paradoxically became its main fixation. In clinging to a doctrine of perpetual confrontation, the Algerian state reenacts the familiar script of authoritarian regimes that, having militarized their diplomacy and ideologized their internal security, ultimately collapse under the weight of their own system. Like once-overarmed but isolated regional powers such as Gaddafi’s Libya or Assad’s Syria, Algeria confuses influence with intimidation, sovereignty with isolation, deterrence with provocation. Devoid of a forward-looking national project, it turns military power into a strategic dead-end, and its hostility toward Morocco into a sterile doctrine. This closed model—already tested elsewhere at the cost of chaos—leads inexorably to geopolitical stagnation and, eventually, internal disintegration

From Historical Falsification to State Indoctrination: Anti-Moroccan Hatred as the Regime’s Survival Matrix

To fully grasp the ecosystem of this aggressive alterity, one must trace it back to the structural origins of the Algerian regime, whose DNA is shaped by a security matrix long dominated by military intelligence. Since the Boumediene era, this grip has derailed Algeria from any autonomous institutional trajectory, locking its political dynamics into the hands of an opaque, self-referential apparatus. After sidelining Ben Bella and establishing a militaro-technocratic regime, Houari Boumediene constructed a system based on hyper-centralization, rentier economics, and the neutralization of any counter-power. The DRS, successor to early intelligence structures like the SM and later embodied by figures such as General Nizar and General Toufik, gradually hijacked the Algerian state, paralyzing its political evolution in favor of a barracks-bound elite obsessed with retaining control over national wealth.

Morocco, despite having actively supported Algerian independence fighters, providing arms, cadres, and refuge to the National Liberation Army from its eastern provinces, has paradoxically been cast as a primary enemy by this amnesiac military-security elite, incapable of acknowledging the historical legacy of Maghrebi solidarity. Among the many Moroccans who contributed to Algeria’s independence, the figure of Mohamed Hamouti, known as the “African Soldier,” stands out. Fighting alongside Algerian resistance in the eastern maquis, his commitment epitomized the unwavering support of the Moroccan monarchy and people for Algeria’s liberation. Far from being opportunistic, this support stemmed from a shared Maghrebi vision grounded in freedom, unity, and postcolonial emancipation. That this memory is now repressed reveals the degree of historical distortion required to sustain a conflictual narrative.

In this architecture of suspicion, the security apparatus was never limited to repression—it evolved into an ideological factory. The DRS, and its rebranded successors, systematically reshaped Algeria’s collective perception of Morocco into that of an existential threat. This internal disinformation campaign erased from textbooks, official histories, and public memory the fraternal bonds between the two peoples, replacing them with a paranoid binary narrative. A slow-motion indoctrination emerged, designating Morocco as the root cause of all internal blockages and perpetuating the fiction of a “regional conspiracy” to justify regime immobility. This ideological shift was powerfully denounced by the Franco-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal, whose stance against historical falsification earned him imprisonment by the authorities.

In his writings and public statements, Sansal notes: “Algeria is a country without memory, without a shared narrative, and without a horizon; to survive, the regime has turned Morocco into its substitute myth.” His case exemplifies how the Algerian security state not only neutralizes political opposition but also silences free and critical thought, especially when it dares to deconstruct the mechanisms behind a state-sanctioned hatred turned into doctrine. Rather than investing in innovation, economic diversification, or regional integration, Algeria has poured resources into an industry of suspicion. This politics of fear, built on the methodical cultivation of hostility, has become the regime’s last remaining glue, its only unifying force. This internal lockdown is paired with an external overreach, where Algeria attempts to offset its domestic fragility with an aggressive foreign policy posture.

A Power in Search of Enemies: The Strategy of the Void

This dissonance between historical memory and current strategic posture has deepened with recent geopolitical realignments. Algeria entered a spiral of confrontation with Spain following Madrid’s recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over the Sahara, and relations with Paris have deteriorated due to France’s inability to impose a singular narrative on the conflict. While more and more diplomatic capitals adopt a realistic reading of the Sahara dossier, Algiers has embraced punitive diplomacy, suspending gas contracts, threatening partners, and isolating itself from long-time allies.

Meanwhile, Algeria continues to squander billions of dollars in energy windfalls to prop up a puppet entity - the Polisario - which now functions more as a disruptive tool than a credible actor. By several cross-checked estimates, Algeria has spent over $10 billion since the 1970s to keep the Polisario afloat, without securing any durable strategic gain. This obsession with a movement lacking social legitimacy or territorial roots, financed at the expense of the Algerian people’s real needs, illustrates the regime’s inability to define a vision of power beyond conflict manipulation.

At its core, this endemic hostility reveals Algeria’s difficulty in existing on its own terms, without a designated adversary or an external threat onto which it can project its internal dead ends. The absence of any meaningful regional integration plan, the systematic rejection of Maghrebi complementarity, and the repeated use of defensive nationalism as the regime’s only cohesion tool, all point to a logic of isolation that runs counter to the great currents of history. In contrast, Morocco capitalizes on its civilizational heritage, institutional adaptability, and strategic foresight to forge lasting partnerships and position itself as a pivotal state in the global reordering. This peaceful, structured rise, grounded in political legitimacy rather than oil rents or diplomatic theatrics, deeply unsettles Algiers.

Thus, Algeria’s resentment toward Morocco is neither a passing misunderstanding nor a purely geopolitical calculation, it reflects a strategic disarray, an unresolved identity wound, and a regime’s failure to project itself beyond antagonism. In this configuration, state hatred becomes a substitute language, a smokescreen masking the inability to envision a credible future, both domestically and regionally. But no future is built on hostility. Because beyond resentment, there is no lasting influence, no sustainable stability, only the illusion of a power that believes it exists because it opposes.

This descent into antagonism is not merely a symptom of weakness, it becomes a self-defeating strategy. For when a regime defines itself through opposition, it forfeits the opportunity to define its own purpose. History teaches us that regimes based on hostility inevitably lose their strategic compass. In constantly pointing fingers at enemies, they forget to chart their own destiny.

By persisting in this institutionalized logic of confrontation, Algeria not only compromises its own prospects for development and stability, it also blocks the path to a Maghrebi project rooted in complementarity, shared resources, and regional integration. In light of these developments, what’s truly at stake in this strategy of manufactured enmity is not just national progress, but the collective future of the Maghreb.