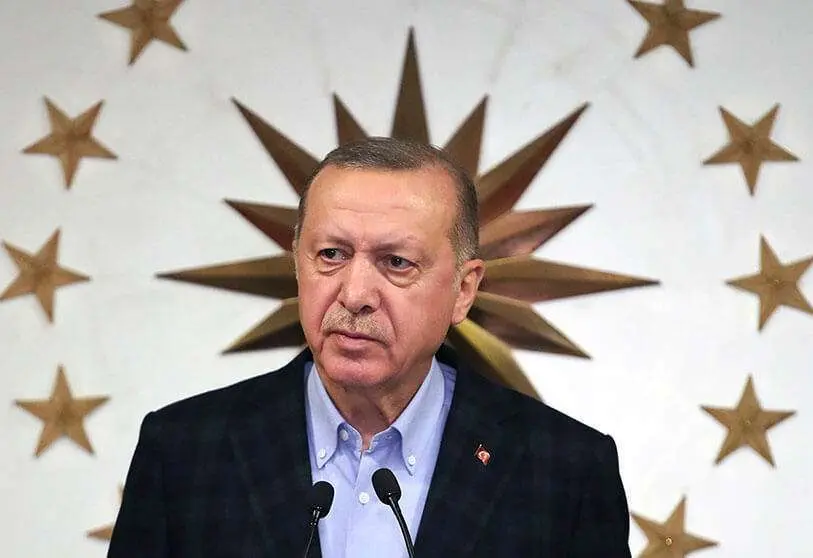

Erdogan tried to favor the Muslim Brotherhood in the 2013 Egyptian revolution

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then Prime Minister of Turkey, "tried to control the history of Egypt, where he had cultivated close ties with the Muslim Brotherhood. This is the main conclusion of one of the latest studies published by Nordic Monitor, a research centre focusing on the Eurasian nation based in Stockholm. The now president - who took office in 2014 - "personally intervened in an event coverage by a private Turkish television network in Egypt in July 2013, ordering the manager to broadcast favourable programmes for supporters of President Mohamed Morsi," the analysis details. This was made known through a telephone conversation - so far secret - between Erdogan himself and Mehmet Fatih Saraç, the chief manager of the Turkish Ciner Media Group, in which the head of government complained "about the event coverage of the Habertük Group's television station and criticized the comments of a guest on a programme in which he was a commentator".

In addition, Erdogan asked him to "use Al-Jazeera as a source", a Doha-based Qatari television station that has become the leading channel in the Arab world and one of the most important in the world, reaching 310 million households in more than 100 countries. The channel has been criticized by the Arab world for allegedly following a pro-Muslim Brotherhood editorial line, in line also with the Qatari government, the main ally of the Egyptian-born organization and Turkey, in front of the quartet formed by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Egypt.

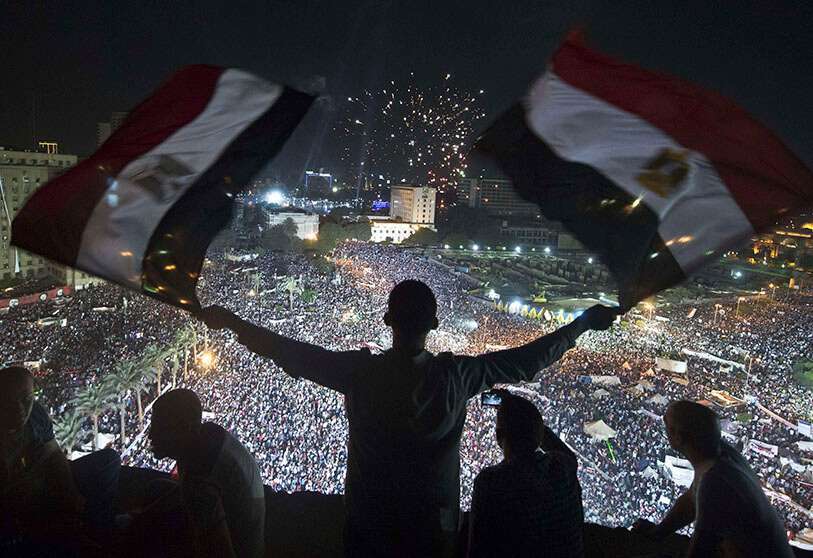

Similarly, the then prime minister, through a loyal employee he had placed in the Turkish private media, gave the order to "minimize the protests against Morsi in Tahrir Square" and, instead, amplify coverage of "a Brotherhood protest in Al-Adawiya Square". "Why don't you connect with Al-Adawiya and its streets," Erdogan asked Saraç. "Sir, the transmission was cut off, they're not broadcasting," he replied. "No, you keep showing Tahrir Square, you always show the streets of Tahrir," the prime minister criticized him, in an angry tone, and later ridiculed the Egyptians who gathered in Tahrir to celebrate Morsi's expulsion and express their support for the provisional government backed by the army.

On the other issue that infuriated Erdogan at the time, it is worth noting that it concerned Ahmet Agirakça, a professor of theology who was invited to a program on the Habertürk network, Pulse of Turkey, to speak about "the strong anti-Morsi sentiment in the Egyptian judiciary, media and politics. "Although I was advocating the Muslim Brotherhood, I was also trying to give a relatively fair picture of the Egyptian political and social landscape. Look, did you hear what Agirakça said,' Erdogan asked, showing his dissatisfaction. What kind of people are these? Shame on you! Terrified by the prime minister's anger, Saraç said he did not understand why the guest had spoken like that. 'I put him on TV, thinking he was our man, but now this has happened,' he apologised, stressing that he would immediately call the Brotherhood in Cairo to correct the mistake,' revealed Nordic Monitor.

"Erdogan's personal involvement in micro-managing the editorial line to direct coverage of a private television network in Turkey against the Egyptian interim government at the time shows how much he had invested in the Muslim Brotherhood and how frustrated he was by the opposition's victory in Egypt. It also confirms how Erdogan and his Islamist politicians were motivated by ideological fanaticism at the expense of Turkish national security interests, which required a balanced approach so as not to antagonize the Egyptian leadership," concludes analyst Abdullah Bozkurt at the Swedish think tank.

In this sense, another investigation by the same author in Nordic Monitor already revealed, last June 18, that Erdogan ordered the calling of protest demonstrations against Egypt's interim government in Turkey, once Mohamed Morsi was evicted from power. In a phone call on August 16, 2013, the head of government spoke with Saudi businessman Yasin Al-Qadi, who has been sanctioned by the UN and the US Treasury Department for his alleged links to the Al-Qaeda terrorist network led by Osama bin Laden, and also a partner of Mustafa Latif Topbas, who is in turn a man in Erdogan's inner circle and a cousin of the chairman of the Aziz Mahmûd Hüdâyi Foundation, accused of being used to spread the Islamist agenda of the Turkish presidency in Africa. During the talk, the then prime minister lamented how recent events in Egypt had overshadowed "all the good things in his life" and that, to remedy this, "important meetings" would be called to "support our brothers in Egypt" with the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet), which controls 90,000 mosques and employs 150,000 imams, at the head of the demonstrations.

The relationship between Ankara and Cairo began to deteriorate in 2013, precisely because of these events. Now, the differences between the two administrations seem irreconcilable, with open fronts in foreign policy, such as the war in Libya, and in domestic policy, as already mentioned, with the destabilising role of the Muslim Brotherhood supported by the Eurasian nation. Mohamed Morsi came to power on 30 June 2012, becoming the only democratically elected person in the country's history. However, his authoritarian drift forced a coup d'état against him on 3 July 2013, orchestrated by the then commander of the Egyptian armed forces, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.