Strategic priorities for Japan in its 2022 Defence White Paper: China and the Indo-Pacific

This document is a copy of the original published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

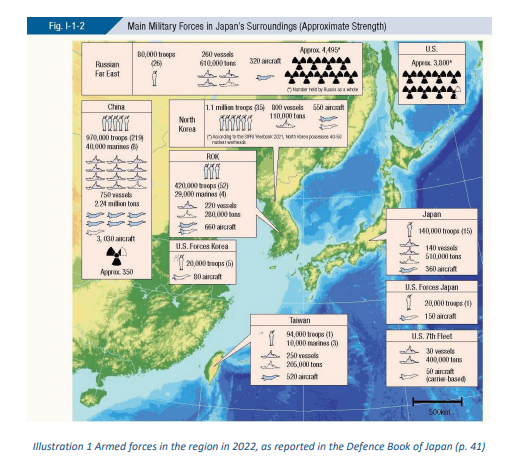

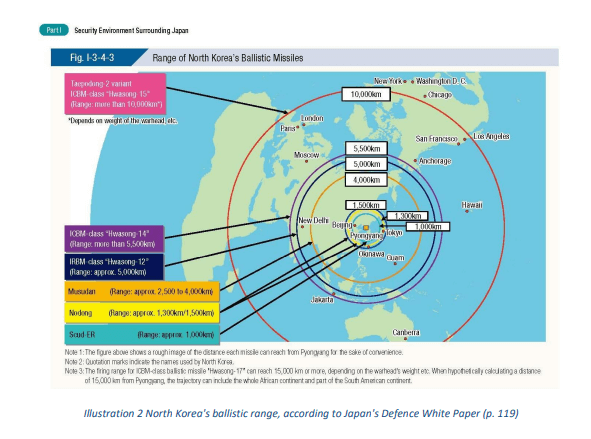

At the end of August 2022, the Japanese Ministry of Defence published the Defence White Paper for this year, a document which, despite not legally committing to any initiative, makes public the main lines of interest for the country's security. The main threats are cited as China, a global power on the rise and with which there is a dispute over the sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands, and the worrying situation in the Taiwan Strait from Japan's perspective, and North and its ballistic missile launches that invade Japanese airspace. The White Paper doubles down on strengthening Japan's traditional defence alliance with the US and on strengthening agreements with third partner countries, in the framework of Japan's vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific as a key area for the country's current and future development.

White papers are documents published by governments to inform the public of their stance on a matter of interest to citizens. Since 2014, Japan's Ministry of Defence has produced an annual Defence White Paper, with updated internal and external security trends for the country, an analysis of strategic defence objectives and alliances with third countries, especially the US. In August 2022, the 2022 Defence White Paper was presented with the traditional structure but with more space devoted to regional risks to Japan in the Indo-Pacific and East Asia, and presenting China and North Korea, albeit in different ways, as the two greatest threats to its stability1.

To this effect, in the geostrategic sphere in East Asia, Japan seems to be torn between reluctance to awaken the Chinese giant, the threat of such an enigmatic neighbour as North Korea, and the continuation of its alliance with the US, which has been in place since the end of World War II.

The assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe last summer reopened the debate over Japan's military projection beyond its borders. Abe advocated increased military spending and an increased Japanese external presence. Among other reforms, in 2015 his cabinet adopted a resolution that went against Japan's traditional pacifist stance since 1945, authorising the Japanese Self-Defence Forces to provide logistical support to armies of allied countries, to take part in military operations and to come to the aid of an allied state under attack, even if this did not involve direct aggression against Japan2.

Japan's Defence White Paper was presented in late summer 2022 by the then Japanese Minister of Defence, Kishi Nobuo3. The war in Ukraine was therefore already in its throes. Consequently, Nobuo's introduction alludes to the Japanese conviction that the international community is facing a crisis unprecedented since World War II. From a Japanese perspective, this is not only because of the risk of international confrontation following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, but also because of the Indo-Pacific area, in a more regional assessment.

In both cases, the war in Ukraine for Europe and the Indo-Pacific situation for Japan, the 2022 Defence White Paper cites similar risks, such as the challenge to the international order and, above all, a confrontation of values and democracies with respect to autocracies. This is in line with the current US vision of the international system of countries, presented as a coalition of democracies led by the US against another group of autocratic or techno-autocratic countries, as we read in the US Strategic Homeland Security Domestic Guidance, published in March 2022, and in the recent National Security Strategy of the Biden-Harris Administration, October 20224.

Japan's White Paper is a statement of intent. It sets out Japan's security and defence policies, although the objectives to be developed are contained in two other documents. The first is the National Security Strategy (NSS), which dates back to 2013 but is currently being updated by the government of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida of the Liberal Democratic Party. And the second is the National Defence Programme Guidance (NDPG), published in 20185.

The National Security Strategy and the White Paper share the objectives of preventing potential threats, supporting UN activities in promoting international cooperation and world peace, fostering a culture of national defence, achieving the necessary military capabilities within the legal limits for Japan, and renewing security agreements with the US6. The publication of a new National Security Strategy is imminent, and it appears that the position on China will represent a major shift in the strategy. Japan can oscillate between joining the current belligerent US position towards China, which would conflict with shared strategic interests, or opting for a current and future bilateral relationship based on dialogue rather than confrontation. September marked the 50th anniversary of the normalisation of relations between Japan and China, achieved in 19727.

The relationship with China and the alliance with the US is a hotly debated topic in Japan. The Ministry of Homeland Security issued a memorandum in September, which contained the views of a number of security and defence experts, who highlighted the risks posed to the country from rising US-China tensions and North Korea's nuclear efforts and cyber security threats, basing their analysis on the conviction that the US would maintain global and regional dominance in East Asia and thus remain Japan's best alliance asset for its security objectives. However, there is also a growing body of opinion against this postulate, convinced of the decline of US power, which will force Japan, sooner or later, to develop its own strategy to cope with external risks8.

The 506-page document is structured in two main blocks. The first is generic and sets out the country's internal and external security needs and objectives, while the second alludes to specific regions, countries and alliances. The first section, divided into four chapters, starts with a preamble with current trends in Japan's security environment and then devotes single-subject chapters to comparing the defence policies of third countries, including the US, China, North Korea and Russia, in addition to broad regions such as Oceania, Southeast Asia, South Asia (India and Pakistan), Europe, Canada, the Middle East and North Africa.

Space is also devoted to trends in new domains, such as outer space, cyberspace, the electromagnetic spectrum, maritime traffic (including here the Arctic) and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, citing primarily nuclear weapons.

In a final section of the first chapter, the impact of climate change on the security environment and the military, both globally and specifically in Japan, is analysed.

The second chapter defines the basic concepts of Japan's security and defence, such as constitutional boundaries, the basis of defence policy and the outline of the National Security Strategy, including the organisations responsible for it, including the National Security Council and the structure and organisation of the Self-Defence Forces.

The third chapter contains the so-called three pillars of Japan's defence, or the means to achieve its objectives. It sets out what Japan's own national defence architecture is, including not only the conventional domains but also the grey zone, remote islands, outer space, cyberspace, the electromagnetic spectrum, catastrophes and disasters - even literally quoting COVID-19. To this end, the paper analyses activities and legislation to date in these areas. The three pillars for Japan's defence set out in the White Paper are:

- Treaties and missions with third countries, based on and limited by Japanese security legislation.

- The strategic partnership with the US.

- Security cooperation with other states and with respect to sea lanes, outer space, cyberspace, arms control and non-proliferation, in all cases citing the UN framework for action9.

Last, the second part of the White Paper focuses on the so-called core and central elements for Japan's security. It is here that the two main geopolitical factors appear, one from the point of view of singularity and the other from the stance of globality. First, China emerges as the state that constitutes the main regional threat to Japan. It then goes on to analyse the situation in the Indo-Pacific, as an unavoidable strategic zone where international actors are multiplying.

The word "China" is mentioned more than a thousand times in the White Paper, which is a sign of the importance Japan attaches to its neighbour, the Asian giant. Minister Nobuo's words on China in his introduction shed light on this Japanese vision:

China continues to unilaterally change, or attempt to change, the status quo with coercion in the East China Sea and South China Sea. The country's ties with Russia, an aggressor nation, have deepened in recent years, with joint navigations and flights in the areas surrounding Japan with Chinese and Russian ships and aircraft. Moreover, China has made it clear that it would not hesitate to unify Taiwan by force, further increasing tensions in the region.

Regarding China, the White Paper analyses the civil-military technological fusion, which has significantly increased China's military resources, plus its intelligence through the use of Artificial Intelligence or 5G, building a very powerful military that is a direct threat to Japan's security and defence. The immediate focus is on sovereignty over the archipelago of five rocky islets in the south-western tip of the South China Sea, the Senkaku for Japan and the Diaoyutai for China, which both nations claim.

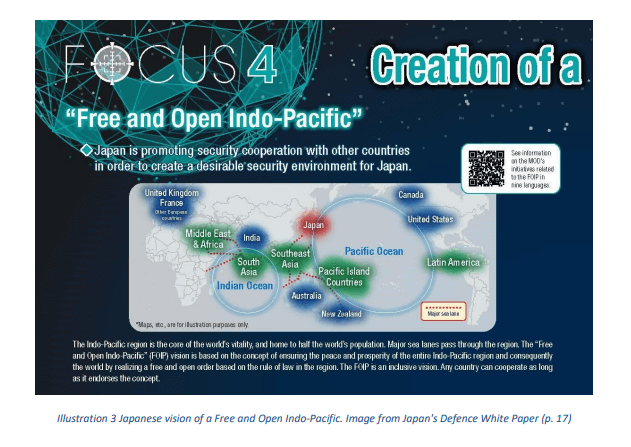

However, it is not only with China that there is a dispute of this nature, but the South Korean government has condemned Japan for its claim to the Dokdo Islands, which are listed as Japanese sovereignty in the White Paper, whereas for the South Koreans they are their own territory in terms of history and international law10. Another sticking point for Japan vis-à-vis China is the need to maintain stability in the Taiwan Strait, in line with the so-called Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision of an open Indo-Pacific with unthreatened sea lanes. The maritime area around Taiwan is vital for the traffic of goods and merchandise to Japan, such that rising tensions and the possibility that China might seek reunification by force pose a major threat to Japan's overall stability.

However, Japan is not closing the door on finding points of agreement with China and advancing along a path of dialogue and respect for each country's own interests. In mid- November 2022, Prime Minister Kishida met with President Xi Jinping in Bangkok on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, with the aim of bringing the bilateral relationship back on track11.

The Defence White Paper will be complemented by a forthcoming Indo-Pacific Plan, as announced by Prime Minister Kishida12, in which Japan's central tenets will be based on security vis-à-vis China's regional ambitions and also on the destabilisation, not only locally but globally, of North Korea, because of its repeated ballistic missile test launches over Japanese airspace since 2017, which Japan has publicly announced as a risk to the entire international community13.

Japan is dependent on foreign resources, which include everything from food to raw materials and energy supplies. The need to keep the sea lanes open to ensure that these goods are traded freely is of paramount importance to the country's national security. Its strategic calculus is therefore not limited to the geographical limits of Japan's own territory but includes the surrounding seas. Japan's Defence White Paper states that changes in global power balances are posing serious challenges, especially in the Indo-Pacific region, a geopolitical area considered central to this struggle.

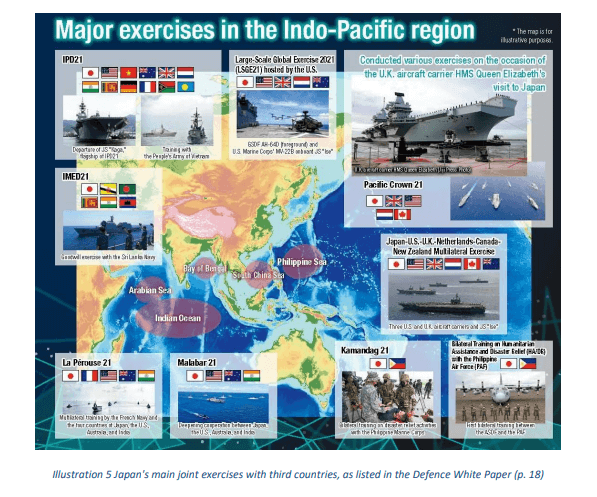

The Indo-Pacific is cited 262 times in the document, appearing as an unavoidable region in Japan's various security, defence and general foreign policy alliances. The area's vision in the White Paper is to promote the defence of Japan's interests in the area through international cooperation and military exercises with allied countries, within the FOIP vision.

Indeed, this strategic vision is in line with US foreign policy, with the White Paper even citing the March 2021 US Domestic Guidance as a benchmark. In turn, the Biden-Harris Administration's National Security Strategy, published in October 2022, is in line with Japanese thinking that the Indo-Pacific region is currently experiencing a level of risk not seen since World War II14.

For its part, NATO's latest strategic guidelines, which came out of the last summit in Madrid in June 2022, include the Indo-Pacific as a focus for the Alliance15. Although Japan is not part of the Alliance, Prime Minister Kishida called for focusing the Alliance's attention beyond the war in Ukraine and in support of Japan's Asia policy16. With respect to the Alliance, Japan's increase in defence spending, reflected in the regular budget increase, is in line with the goal of reaching 2% of GDP over the next five years, which in turn is in line with the Alliance's target for all Alliance members17.

In the White Paper, the term used for the US-Japan alliance is “unbreakable”. This union stems from the agreements between the Americans and the Japanese at the end of World War II, in a scenario of total Japanese defeat and near American protectorate over the Asian country. The alliance was ratified by the Washington Treaty of 19 January 196018. More than sixty years have passed since these events, although they are still very much alive in Japanese memory, society and politics. The White Paper advocates an indissoluble bond between Japan and the US in foreign policy and security matters.

For its part, in the US Indo-Pacific Strategy19, Japan is cited as a key ally in the region for the Biden Administration, along with South Korea, under whose mandate bilateral meetings between the two nations have multiplied20.

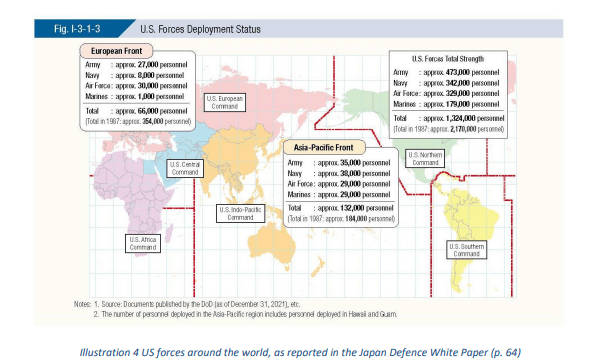

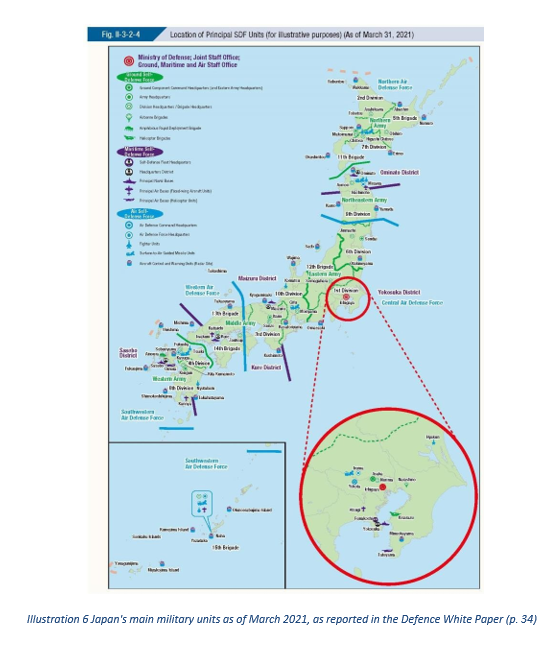

The US has almost eighty military installations in Japan, the largest permanent presence of US troops in a foreign country, with the bases in Honshu, Kyushu and Okinawa the most important. In turn, Japan helps fund the presence of this contingent through the Host Nation Support programme, at a total cost to Japanese coffers of $1.8 billion per year21. To this effect, since 1986, the Japanese Self-Defence Forces and the US Army have been conducting the biennial Keen Sword joint exercise, designed to increase the readiness and interoperability of the two forces. The latest edition took place last November, with the involvement of 36,000 troops, 370 aircraft and 30 ships22.

The solid alliance with the US does not prevent Japan from cooperating with other countries in the region, the White Paper citing Australia and India as preferential partners, with whom it advocates multilateral or bilateral treaties with second countries, such as the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) signed with Australia in January 2022, which authorises the military forces of the two countries to train and operate in each other's respective territories23.

Last, the presence in the Indo-Pacific of European states (the UK and France), cited individually in the White Paper rather than the EU as a whole, also appears as a strategic alliance for Japan. In this regard, we should not forget Japan's various joint military exercises with some EU countries. An example close to home is the maritime manoeuvres with the Spanish Navy, carried out periodically since 2018 and which this year 2022 took place in the Strait of Gibraltar24.

The White Paper sets out the need to increase Japan's warfighting capabilities to meet its strategic objectives25. However, according to Article 9 of the Constitution, which dates back to 1947, Japan can possess a maximum war capability only for self-defence, although the specific limit depends on changes in the international situation and the level of technology. The possession of weaponry consisting of intercontinental, ballistic missiles, long-range bombers or aircraft carriers, for example, would exceed this necessary level for self-defence and is not constitutionally permitted.

Similarly, in the 1957 fundamentals of Japan's defence policy, it is stated that the objective is to prevent or repel aggression, safeguarding the country's independence, peace and democracy while, under no circumstances, can Japan become a nuclear power or possess weapons of mass destruction, including biological weapons. Recently, however, the limitations that also prohibited arms exports to third countries have been lifted26.

The White Paper calls for an increase in the resources allocated to the country's security and defence, and for urgent action:

As a means of defending itself against any change in an international order based on universal values, Japan should not delay in pooling its knowledge and technology, committing all its collective efforts to strengthening its national defence capabilities27.

Indeed, after a decline due to the COVID pandemic, at the end of 2021 the Diet of Japan approved a record defence budget for 2022. The expenditure is 5.4 trillion yen ($47.2 billion), justified by the need to equip itself against the Chinese power and better coordinate with the US military. For the eighth consecutive year in history, this figure is the highest yet allocated to defence28.

Alongside this increase, Japanese governments have also sought to expand the capabilities of the Self-Defence Forces, likewise justified by increased Japanese international cooperation and involvement in security issues. As Japan's strategic perspective turns to the threat from China and North Korea, plus the need to ensure that the area's sea lanes remain open, its Self-Defence Forces emphasise greater mobility and amphibious capability. To this effect, in 2018, the creation of a 2,100-strong amphibious brigade and a central command to control the five land, sea and air forces was announced29.

The main focus is on combat aircraft programmes. The Japan Air Self-Defence Force (JASDF) primarily currently operates three types of aircraft: the US Lockheed Martin F- 35 and F-15J Eagle, and the F-2 built entirely by Mitsubishi.

Another fighter aircraft is currently being developed with the UK and Italy to enter service around 2035 to replace the F-2, although this initiative does not have US backing30, while in July 2020, Boeing and Mitsubishi reached another agreement to implement an F-15 upgrade programme at an estimated cost of $4.5 billion. The project must be completed by 31 December 2028, according to the US Department of Defence statement31.

In recent decades, strategic competition between the major nations of the Indo-Pacific has intensified. This competition is the main element of Japan's 2022 Defence White Paper, which links China's aggressive behaviour to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Japan has aligned itself with the US and other allies in condemning and sanctioning Russia, even to the extent that there have been some diplomatic incidents between the two countries, including the expulsion of the Japanese consul in Vladivostok, accused of espionage32. Ultimately, the paper's key areas of focus are analyses of the rise of China

- supported by Russia - international cooperation and the creation of a free and open Indo-Pacific region.

The key focus of the White Paper is deterrence, which is vital to prevent changes in the status quo in the region for Japan. This means boosting Japan's international cooperation in all areas of warfare, including outer space and cyberspace, and working to strengthen its historic alliance with the US. As a backdrop, there is the regional conflict, mainly with China, with whom Japan is in dispute over the sovereignty of some rocky islets; and North Korea, a country that is as enigmatic as it is destabilising, first and foremost with respect to Japan itself, with the periodic launching of ballistic missiles in tests that inflict damage on Japanese airspace.

One of the key principles vital to Japan's defence security is the Indo-Pacific region, given that the main sea routes of communication and supply for Japan run through this region. Since 2016, Japan has been advocating and promoting its vision of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), aiming to ensure peace and stability throughout the region, while maintaining an international order based on treaties and rules, beyond the aforementioned alliance with the United States. To this effect, Japan is promoting bilateral initiatives with India, Australia and some European countries, always within the framework of promoting its initiative to make the Indo-Pacific region a free and open area33.

Japan is also working to keep the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) group of Australia, India, the US and Japan active. In September, the Kushida government presented some priority issues to the other QUAD countries, including the cyber security of critical infrastructure and the need to secure supply chains34.

In terms of Japanese domestic policy, the White Paper is a declaration of intent in the perception of the country's security threats and challenges. However, a new National Security Strategy has been announced, with objectives to be implemented in Japanese regulations and political guidelines and, as evidence of its concern, Japan is increasing defence spending year by year, something that is difficult to reconcile with a markedly pacifist Constitution, although it is justified by the different governments as a response to regional threats from actors such as China and North Korea. Japan's Self-Defence Forces have very limited development unless the country's basic security legislation is changed to bring it in line with the times.

Regarding the debate on the defence budget, the current Japanese prime minister, Kishida, feels that since the death of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, heated discussions about its increase have escalated, as Abe was a standard-bearer for this, making it a main target of his Japan's security policy. However, Kishida is adamant that its increase should be modest, especially in an unstable economic climate, including the ravages of the COVID pandemic, although a new national security strategy to replace the outdated one of 2013 is in the pipeline and it remains to be seen how the defence budget will take shape in the near future.

Javier Fernández Aparicio

Analyst at the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies

@jafeap

References:

1 Japan's Defence White Paper is a public and open document, available on the website of the Japanese Ministry of Defence: Publications | Japan Ministry of Defense (mod.go.jp) (accessed 25/11/2022).

2 BALLESTEROS, Alberto: Shinzo Abe: nine years of reform in Japan - The World Order - EOM (17/01/2021, accessed 25/11/2022).

3 2022 Defense of Japan Report - USNI News (24/08/2022, accessed 26/11/2022).

4 National Security Strategy. The White House: Biden-Harris Administration's National Security Strategy.pdf (whitehouse.gov) (12/10/2022, accessed 25/11/2022).

5 National Defence Programme Guide. Ministry of Defence of Japan. National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) and Medium Term Defense Program (MTDP) (mod.go.jp) (accessed 25/11/2022).

6 Security Strategy (NSS). Ministry of Defence of Japan. National Security Strategy (NSS) (mod.go.jp) (accessed 25/11/2022).

7 KAWASHIMA, Shin: Japan's national security strategy: a delicate task - The Diplomat (18/03/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

8 MATSUMURA, Masahiro: Japan's national security strategy update already looks outdated - Nikkei Asia (20/09/2022, accessed 26/11/2022).

9 In fact, a traditional demand of Japanese diplomacy for some time now, in line with the position of other countries such as India, Germany and Brazil, has been to reform the United Nations Security Council so that Japan becomes a full permanent member. See Japan advocates reforming the UN Security Council and becoming a permanent member (lavanguardia.com) (22/09/2022, accessed 23/11/2022).

10 Prospects for Japan and the Koreas to end-2022 - Oxford Analytica Daily Brief (oxan.com) (24/11/2022, accessed 26/11/2022).

11 JHONSTONE, Christopher B.: Kishida Meets Xi Jinping | Center for Strategic and International Studies (csis.org) (15/11/2022, accessed 26/11/2022).

12 Japanese PM Kishida Lays Out Indo-Pacific Strategy in Shangri-La Speech - USNI News (15/08/2022, accessed 26/11/2022).

13 North Korea: Regime Conducts Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile Overflight of Japan (stratfor.com) (04/11/2022, accessed 25/11/2022).

14 QUOTE ESN Indo-Pacific IIWW

15 Special Report: NATO's Indo-Pacific Strategy Needs Japan - NAOC (natoassociation.ca)

16 Japan's vision at the NATO summit | International | EL PAÍS (elpais.com)

17 An Analysis of Japan's Defence White Paper 2022 - CAPS India

18 LLANDRÉS, Borja: Japan and the United States, 60 years of alliance (atalayar.com) (13/03/2020, accessed 27/11/2022).

19 Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States. The White House: U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf (whitehouse.gov) (02/2022, accessed 27/11/22).

20 SMITH, Jeff M. The Indo-Pacific Strategy Needs Indo-Specifics - Defence One (15/02/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

21 NXT Rocket (forecastinternational.com)

22 TEJEDOR, Alberto: US and Japan mobilise 36,000 soldiers, 30 ships and 370 planes for military manoeuvres with an eye on China and North Korea (larazon.es) (11/11/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

23 Australia, Japan: Leaders Will Meet to Sign New Bilateral Security Declaration (stratfor.com) (18/11/2022, accessed 25/11/2022).

24 Japan-Spain Bilateral Exercise | Embassy of Japan in Spain (emb-japan.go.jp) (20/06/2022, accessed 26/11/2022).

25 NEW, Marta: Japan wants to become a military power again - The World Order - EOM (30/06/2022, accessed on 27/11/2022).

26 CALVO GONZÁLEZ-REGUERAL, Carlos. Japan's Defence Policy. IEEE Opinion Paper 122/2020. http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_opinion/2020/DIEEEO122_2020CARGON_Japon.pdf and/or bie3 link (accessed 24/11/2022).

27 Tokyo may allow export of lethal arms - Oxford Analytica Daily Brief (oxan.com) (18/11/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

28 KOSUKE, Takahashi: Japan Approves Record Defense Budget for Fiscal Year 2022 - The Diplomat (27/12/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

29 Global data for Japan taken from Forecast International Military Markets: Rocket NXT (forecastinternational.com) (06/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

30 SORIANO, Ginés: Japan, UK and Italy join forces on a sixth-generation fighter (infodefensa.com) (23/11/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

31 Japan: U.S. to Replace Some F-15s on Okinawa With F-22s (stratfor.com) (27/11/2022, accessed 23/11/2022).

32 Japan: Consulate General Expelled From Russia Over Spying Accusations (stratfor.com) (27/09/2022, accessed 28/11/2022).

33 Japan will pursue joint weapons projects with Europe - Oxford Analytica Daily Brief (oxan.com) (18/08/2022, accessed 27/11/2022).

34 Quad statement sharpens spotlight on ransomware - Oxford Analytica Daily Brief (oxan.com) (26/09/2022. Accessed on 27/11/2022).