The Americanisation of Spanish politics

- The bet on the character

- The enslavement of emotions

- Drama as raw material

- Foul play defeats the enemy

American know-how on how to do politics affects everyone.

American politics is usually linked to British politics because they are Anglo-Saxon, but this is a mistake. The reality is that American politics affects everyone, in style, in dissemination and in the way politics is done. Many of the techniques observed in the great figures of Spanish politics such as Pedro Sánchez or Isabel Díaz Ayuso are copies of the style book created by the Americans and, later, the British.

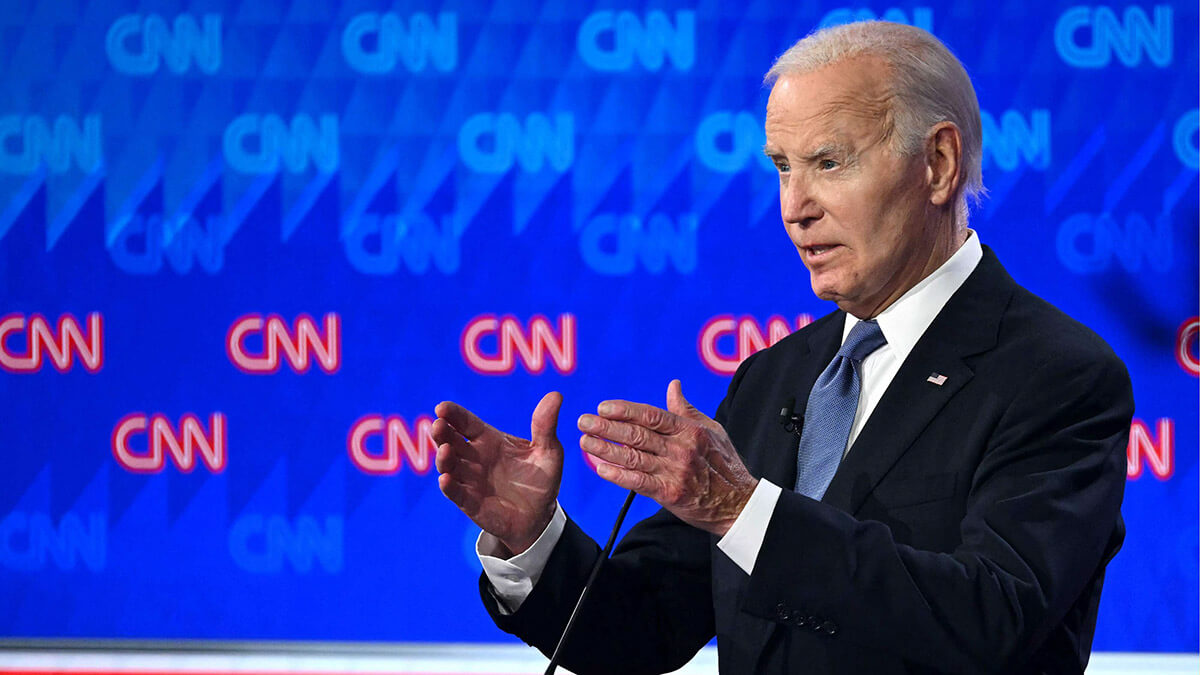

The Trump and Biden ‘phenomenon’ is a current reflection of the Americanisation of politics in its purest state; no doubt Spanish politicians' advisers will study Trump's successes and Biden's failures (leading to his resignation) to apply them to their own candidates.

Spain suffers from the same syndrome as the US, the perpetual campaign. Despite laws limiting the duration of an election campaign to 15 days, there is constant competition between politicians. Every public appearance, every press conference and every message on social media is a strategy to win votes. This trend is inherited from the United States.

The bet on the character

Personification is a key element in Spanish politics. Sánchez is a figurehead, a symbol of both his party and the left. Strategic voters who consider themselves ideologically affiliated with the PSOE can vote for the opposition if they do not like the figure of the current president. This means that, though unnoticed by many, character trumps ideology. It is the reign of the personification of politics.

This phenomenon has its origins in the advent of television. Theories of political communication (formerly known as propaganda) show in this new medium a rupture in the figure of the politician. Suddenly the role of the politician is divided into two roles: the professional role and the stylistic role. The former focuses on the politician's achievements, experience and failures. The second focuses on the politician as a person, his family, his friends, his hobbies and his appearance.

The exploitation of the latter is exemplified by the figure of Kennedy. When advertising agencies began to be the creators and managers of American politicians' campaigns, the stylistic role was formally born.

Eisenhower was the first to hire an advertising agency, creating a trend that became formalised, materialising in the figure of the political or communications consultant. John F. Kennedy is the example followed by emblematic politicians such as Obama (although many believe him to be the first to use his personal image as a campaign strategy, political communication analyses show that he used Kennedy's roadmap) as well as many international politicians. Kennedy was portrayed and is remembered as a young, athletic and handsome man. He was made the emblem of the ideal man, the perfect father, an exemplary husband, a sportsman of excellence, and so on. The reality is that Kennedy had serious back problems and was unfaithful to his wife.

The exploitation of this ‘political brand’ was so successful that it appeared in Europe with Margaret Thatcher and her advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi (known colloquially as Thaatchi & Thaatchi) and spread progressively. In Spain, this has been applied to politicians such as Adolfo Suarez, José María Aznar and Mariano Rajoy. In the case of Aznar, he was linked to paddle tennis, a sport of the elite, something that was coherent with his electorate and that brought him closer to them; it made them see themselves reflected in him.

When asked about the election of Adolfo Suarez, many people comment on his charisma, his ability to mobilise the population with his words and his physical attractiveness. At the same time, Rajoy is a great example of the collapse of the stylistic role. Rajoy, mainly, did not know how to speak in public, something reflected in his nervousness when speaking and moving (self-adapters and object adapters). Part of the deterioration of his public image could be attributed to his weakness in his stylistic role.

Sanchez's first elections illustrate the personification today. Both national and international media highlighted that he was handsome, tall and young. It is known that he likes football, that he is an Atlético de Madrid affiliate, his love affair with his wife and much more. These elements are exploited by his advisors; they appear in his speeches, in his public appearances or in his political advertisements in order to humanise him and bring him closer to the public. This, without the Americanisation of politics that created the figure of the political advisor, would be inconceivable.

With Trump's current campaign, Spanish advisors are going to use elements of him as a draft for their own strategies. Trump's strength is his persona. He is so powerful that he manages to mobilise segments of the population that, previously, were not so radical. His stylistic role is his greatest weapon and it is so effective that it is one of the main reasons why Biden resigned.

The enslavement of emotions

The evolution and exploitation of the stylistic role, coupled with the fact that individuals have shorter and shorter attention spans, messages are adapting to this new landscape. Emotions are not just one element, but the entire discourse for many politicians. The dominance of images has made political messages short, simple and impactful in order to make headlines and have a greater impact.

Emotions rule and guide every message, every press conference and every political event. According to Aristotle and many later theorists, emotions are a powerful weapon in both rhetoric and oratory. Part of the reason Trump has been so successful is his use of emotions to engage Republican voters and win their loyalty. He doesn't speak to their heads, he speaks to their hearts.

The dominance of American political advice permeates Spanish politics and is reflected in the harnessing of emotionality. Gabriel Rufián's speeches in recent years are a prototype of this phenomenon. They are all permeated by ethical, moral and emotional issues.

When analysing his speeches, it is worth noting the triumph of the argumentative and rhetorical figures he employs. He uses fallacies that can be compared to those of American politicians such as Trump, as well as appealing directly to the listener and to the sense of patriotism.

The rise of nationalism allows politicians to include symbolic words related to this movement in their repertoire, and Catalan independentism benefits from this. Rufián stirs up those who sympathise with this independence movement while constructing the extreme right as the enemy. The repetition of warlike messages towards this opposition and words such as ‘nation’, ‘freedom’, and ‘independence’ are a weapon he applies fiercely and to good effect. The repetition of a simple message, according to the Americanisation model of politics, ensures that the public's attention is not dispersed and that the message is embedded in the public's mind.

Drama as raw material

The transformation of politics into spectacle is something that the Americans have mastered and from which Spanish politicians are learning. It must always be taken into account that, when translating American political phenomena into Spanish ones, the calibre is different due to cultural as well as population differences. Despite these differences, the spectacle effect is the same.

Stages are meticulously chosen, appearances are taken care of, body language is controlled to perfection, and so on. Due to an electorate increasingly disenchanted with politics, many use ‘infotainment’ to gain media coverage and attention. The normalisation of Republican and Democratic rallies and merchandising, such as Trump's, demonstrates this (a phenomenon that Spanish politicians are replicating with political party online shops).

For many political communication experts, the first televised election debate between Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960 was decisive for Kennedy's victory. The young candidate wore a crisp suit, was well groomed and made up, stood up straight and was charismatic. Kennedy conveyed a sense of hope, transition and a promising future. At the same time, Nixon was wearing a grey suit, was sweating and was not groomed. The choice of a dull colour made the public perceive him as tired, outdated and old-fashioned. In post-debate polls, radio listeners claimed that Nixon was the winner, but those who had watched the debate on television said the opposite.

This has translated in Spain into events such as televised election debates, insults between members of the government in interviews and government control sessions on Wednesdays. Electoral advertising itself is a reproduction of American advertising, especially video advertising. They are panoramic, cinematic, with emotional and dramatic messages. They showcase the personal stories of politicians to show the audience that they can empathise with them, that they are one of them.

Foul play defeats the enemy

The personalisation of politics leads to the application of ‘dirty politics’ tactics, i.e. personal attacks on things that are not related to politics. Exploiting the weakness of the opposition to win an election is not inherently negative, but dirty games have turned elections into real battlegrounds.

Often, after government meetings or scrutiny sessions, politicians engage in verbal duels with their opposition instead of talking about policy. Negative campaigning is increasingly used to turn the adversary into the enemy and is one of the most controversial elements of today's politics, both American and Spanish. Despite the ethical questions raised by this tactic, name-calling has proven to win battles.

Spanish politics has reproduced and followed the school of American political consultants and communications agencies. Fundamentally, Spanish politics is deeply Americanised.