The rise of China as a maritime power

This document is a copy of the original published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

Since the 1980s under Deng Xiaoping, and taken up by subsequent leaders of the People's Republic of China, the country has been opening up to the world, developing on the basis of a market economy with Chinese characteristics, and for economic and commercial as well as historical reasons, the country is once again looking to the sea.

Without ceasing to be a continental (land) power, China began to develop as a maritime power in all its facets to 40 years later become a "great maritime power" with enormous influence throughout the world. Nowadays, it is almost on a par with the United States, the great and almost hegemonic maritime power for the last 80 years. This paper analyses this evolution and the strong support of the Chinese state to effect this transformation, and identifies some of the elements causing geopolitical tensions derived from China’s rapid rise to the status of maritime power.

Introduction

In 2012, during the 18th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the then outgoing President Hu Jintao made a clear call for China to become a leading maritime power1 . The inclusion in the congress report of the need to safeguard China's maritime interests, and the goal of becoming a major maritime power, placed this issue at the heart of the CCP's policy agenda. Hu identified four key elements for progress in this area: the ability to exploit ocean resources; the development of a maritime economy; preservation of the marine environment; and the protection of China's maritime interests and rights2.

Albeit more pragmatically, as early as 2000, then President Jiang Zeming declared that building a great maritime power was an important historical task for China3.

In 2013, shortly after assuming the presidency, Xi Jinping advocated that China had to become a "truly great maritime power” not only to consolidate its maritime dominance, but also as part of a national strategy designed to link military issues with strategic interests relating to sovereignty, regime legitimacy and great power politics4.

In July 2013, during a session of the Political Directorate of the CPC Central Committee, Xi sent the clear message that China must protect its "maritime rights and interests", and that to do so it had to develop the corresponding plans, always within a peaceful framework, and in no case must it renounce the rights and interests it considers legitimate. Xi wanted to advance the development and exploitation of resources in areas over which he considered he had sovereign rights, clearly the South China Sea (SCS), seeking friendly and mutually beneficial cooperation with other countries, using peaceful means and negotiations to resolve disputes and seeking to safeguard peace and stability5.

All these declarations, and the corresponding policies and actions derived from them, with particular emphasis on those implemented by Xi Jinping, are intended to send the message that a China that has become the world's second economic power and a major global trading power does not want to and cannot limit itself to being the continental power it has traditionally been considered to be. In short, China is called upon, and for reasons of its own subsistence is left with no choice, to become a major maritime power, and in this sphere it is clearly ready to defend both its interests and what it considers its rights.

What do we mean by maritime power?

First of all, it seems pertinent to clarify what we mean when we refer to maritime power and sea power, and how these relate to naval power and naval powers. Is a maritime power always a naval power, too? Does maritime power imply naval power? And conversely, does naval power imply maritime power? These terms are sometimes used almost interchangeably, and can lead to confusion and misunderstanding.

Geoffrey Till in his book Seapower6 considers that Mahan himself, in his reference work "The influence of Sea Power upon History (1660-1783). History of Naval Warfare", does not explicitly define "seapower". Notably, the translation of the title into Spanish "Influencia del Poder Naval en la Historia” may give rise to confusion in that it translates "sea power" as "naval power", when in fact another viable translation is "maritime power". However, there is also some logic in the translation, the second part of the title, "History of Naval Warfare", forcing the choice of term by essentially referring to the history of naval warfare, thereby linking "seapower" to the specifics of what is considered “naval” rather than “maritime”.

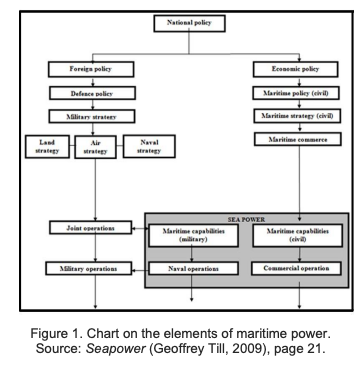

In this somewhat ambiguous scenario, where the same words are used but mean different things to different people, Till7 tries to explain the meaning of "seapower", which he clearly translates as "maritime power"8, by dissecting it into its two components.

First, there is the idea of "power", understood as potency and carrying a twofold implication, the first referring to the contributions, to the strengths (economic, military, political, or other) of nations, in essence to the means they have; and the second to the consequences of these strengths, understood as meaning that a country is powerful because others do its will (it influences others).

And then there is the label "sea", which linked to various types of sea-related activities can refer either to those of navies, acting alone or with land and/or air forces (which would be eminently naval); or to navies in the broader context of activities relating to the commercial and non-military use of the sea (maritime).

As Till's graph shows, sea power is not simply the grey ships (warships) of countries' military navies, but it also encompasses the contributions of other services, and above all includes other non-military aspects of the use of the sea (merchant navies, commerce, scientific navies, fisheries, shipbuilding, shipyards, etc.).

Since this paper seeks to delve deeper into the rise of China's maritime power, it is relevant to highlight the view of this concept from Chinese eyes. Zang Shiping, who published “Chinese Sea Power” in 1998, considers that in its simplest interpretation,9 maritime power is the freedom to carry out activities in the maritime domain. The author emphasises that for maritime nations, maritime power is not a goal but an indispensable means of ensuring a nation's survival and sustainable development. He divides maritime power between purely military power (relating to one side in a conflict over control of a maritime space), and what might be termed global or comprehensive power (which includes political, economic and military factors). And he identifies the four elements affecting maritime power in the world today: naval forces (military in the maritime domain), maritime entities, oceanic development and maritime legal systems. We see that this approach is conceptually quite close to that of Geoffrey Till.

Because of its relevance, we can also add the definition10 of "Great Maritime Power (GPM)" as identified by Liu Cigui, Director of Ocean Affairs in the Chinese Administration, in an article published shortly after Hu Jintao's statements, where he considers a GPM to be a country with sufficient ability and power to develop, exploit, protect and control the ocean. The author goes on to detail what such a GPM should look like: Its marine industries should constitute an important part of the country's economy; it should have world-class maritime professionals in science and technology and the capacity to exploit marine resources in a sustainable manner; and its defence capabilities should be significant enough to defend national sovereignty, maritime interests and rights, and play an important role in safeguarding peace and promoting the international development of maritime affairs. As we shall see in the following paragraphs, the Chinese roadmap for becoming a maritime power is clearly marked out on the basis of these ideas.

To further deepen understanding of the difference between “naval power” and “maritime power”, we end this conceptual section by drawing attention to the clarifications made by Josep Baqués on the use of these expressions11. The latter, he declares, is broader than the former, encompassing numerous means and activities carried out at sea (military, merchant, fishing, scientific, coastguard, maritime traffic, means for extracting resources at sea, shipbuilding, etc.), while naval power is essentially confined to the military navy and its activities. Naval power can thus be considered to be encompassed within maritime power as a (fundamental) part of it.

China as a maritime power in classic geopolitics.

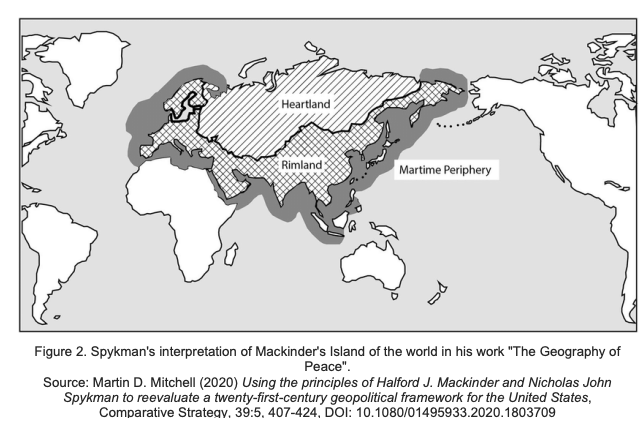

Focusing again on China, and considering the variable of geography, we could say that China is a country in Spykman's rimland or "mainland belt". It has more than 22,000km of land borders (with 14 countries, most notably Russia and India), and a significant sea frontage on the Western Pacific, with a coastline of almost 15,000km.

Geopolitically, China is a more complex actor because although in the classic dichotomy between maritime powers and continental (or land) powers it has traditionally been considered more continental than maritime, it also has elements of the three main classical geopolitical theories (Mackinder, Mahan and Spykman), allowing for a certain breadth in the analysis of its geopolitical reality, which has itself changed throughout history.

Beginning with the maritime geopolitical school, in a rigorous and very interesting study12 on China's aspirations to become a GPM, Baqués analyses the Chinese reality based on the postulates that Mahan considers decisive, which are essentially six13, three geographical (geographical position, physical configuration and size of the territory) and three social (size of the population, national character and character of the government). He concludes that while the economic component and political structures (in their current state and assuming no regression) are factors that may be favourable to China becoming a GPM, its geography may not be so favourable. Being a rimland state, we should not forget that it has important land borders14 to defend, even if there are currently no relevant tensions along any of them. Furthermore, its access to the oceans is not entirely straightforward15, illustrating that geography remains important16.

Within the framework of continental theories, Mackinder defended the geopolitical superiority of Eurasia over the Americas17, a thesis reaffirmed by Bzrezinski in 1998 in his work "The Great World Chessboard". Although Mackinder's "heartland"18 would be geographically what is now Russia and some Central Asian countries, it would also include a part of China19 (the Xingiang region), giving the country a certain continental character. Whatever the case may be, we must not forget that historically, and particularly over the last 600 years, China has been more concerned with its land borders than with its access to the sea.

In the framework of the third classic geopolitical theory, already in the 1940s and closely aligned with Mackinder's theories, Spykman placed the emphasis on the Rimland, arguing that whoever dominated the Rimland would dominate the "heartland" and therefore the world. Based on this idea, he went on to argue that the US objective should be to prevent a "heartland" power from establishing itself in the continental ring20.

Robert Kaplan21 points out that Mackinder himself, in the final paragraphs of his famous article "The Geographical Pivot of History", already made a disturbing allusion to China. Having argued that the Eurasian hinterland was the geostrategic fulcrum of world power, he went on to warn that China could be a danger to the world's freedom in adding to its resources on the great continent (Eurasia) an ocean front, an advantage denied to Russia22, the main tenant of the "heartland". Indeed, Mackinder feared that China might one day conquer Russia, which is certainly food for thought more than a hundred years later given the present circumstances (particularly in terms of its economic, demographic and even political dimensions). Some authors already believe that Russia could end up becoming a vassal state of China23.

To try to understand current Chinese positions within this framework of the three great geopolitical theories, it is useful to go back a few centuries and recall that during the 15th century, the period of the Ming dynasty, admiral Zheng He' s fleet was considered the most impressive ever seen. This historical reference is currently being used by Xi Jinping to emphasise two ideas: that the maritime boundaries of the "Middle Kingdom", of Ming dynasty China, must be relevant and considered in delineating today's borders; and that the economic and cultural character of Zheng's voyages, which did not seek to colonise or conquer any weaker nation but in a benign way sought to establish "harmony24" in all the seas, always under the guidance and light of the Chinese emperors25, of the empire, is a mentality that should guide the actions of today's China.

Turning to geopolitics, various circumstances, in particular the tensions with the Mongols on the northern border and the logical need to reinforce and strengthen the "Great Wall", led to an abrupt end to the voyages of admiral Zheng in 1433, whose fleet was subsequently dismantled.26 China closed inward on itself, becoming an eminently continental, land-based empire and renouncing its maritime aspirations and naval capabilities, which had been central for almost 500 years, since the Song dynasty years at the beginning of the second millennium.

During all that time, China had controlled important parts of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea (SCS), as well as the well-known 9-dash line (in red in Figure 3), which China today claims as a maritime boundary in the SCS based on historical rights, and is in fact simply a reflection of the boundaries of some of the maritime areas that Admiral Zheng's fleet controlled.

Within this theoretical framework, Kaplan27 argues that China has geography on its side, and that this is so obvious and so elementary that it tends to be ignored in discussions about China's economic dynamism and national assertiveness. However, we must remember Baqués’s28 warnings that the country also has certain geographical shortcomings that could play a dirty trick on it, including the fact that its access to the Pacific is far from straightforward (first and second island chains), and that the American (US Navy) blockade capability, particularly in the Strait of Malacca, is potent and should not be underestimated.

Considering that until recent years China has been a distinctly continental nation (with inland areas occupying parts of the Mackinder heartland, while its coasts occupy the Spykman continental ring ), and adding to this China's history as a maritime and naval power up to the 15th century and its renaissance as such in recent decades, we could conclude that we are dealing with a so-called hybrid continental-maritime power that is seeking to29 transform the MSC into a closed or semi-closed sea, and to secure some control over the Strait of Malacca (preventing it from being blockaded). China seeks only to regain (and even extend) the control and influence over the maritime spaces it had in the past, in particular with reference to Admiral Zheng's fleet.

China sets sail. Elements of Chinese maritime power and its development.

From a historical perspective, the "Great Wall", a key element of defence against the northern barbarians, has given China a strong terrestrial or continental character, exacerbated in the last century and in particular during the Mao Zedong period, when Chinese strategists regarded maritime dominance as colonialist and imperialist, and anyone proposing alternative strategies to the continental approach (in particular of the Chinese Armed Forces which were eminently terrestrial) identified as an ideological enemy30. This example of excessive mainland at the expense of maritime has historically had negative consequences and implications for China's development and prosperity.

Deng Xiaoping’s rise to power in 1978 marked a drastic change in the country’s approach to maritime affairs. The era of reform and opening up was ushered in at the 11th Party Central Committee, setting China to sail. The relationship between the oceans and survival, and especially their importance for the country's development, is beginning to become clear31. Examples of this openness include the Chinese navy sending ships abroad in 1985, and the 1991 publication of Zhang Wei and Xu Hua's book "Seapower and prosperity", which openly discusses mainland Chinese culture based on agriculture, and that of Western countries, which represent maritime civilisation, based on trade and raw materials.

The book argues that successful maritime trade requires control of sea lines of communication (SLOCs32) and markets (for both raw materials and manufactured goods), and although it is only a high-level theoretical work, it is significant for its many capitalist and mahanian overtones. It also gives us an idea of how Chinese maritime thinking has evolved, above all the open-mindedness of the new leaders, in an environment that was not straightforward.

Mahan in particular, but Julian Corbett as well, began to be the authors of reference for the Chinese33, the country having realised that if it wanted to become a maritime power it would also have to develop its naval power, or in other words a powerful navy. Memories of the 18th and 19th centuries of humiliations, and of the 20th century too, motivate an economically developing China to learn from past mistakes and to not turn its back on the sea, as it has done since the 15th century.

The indisputable reality is that in a period of barely 40 years, and linked to spectacular economic growth, China has been transformed from a basically continental power into a power with a strong maritime character, a GPM.

Following the definitions and concepts of maritime power included in the previous sections, and considering the separate elements that comprise the concept, of particular interest is the analytical work34 led by admiral McDevitt , which studies the four elements that make up Chinese maritime power: shipbuilding capacity (shipyards), the merchant fleet, the fishing fleet, and what he calls the coercive element, the most significant of the four, consisting mainly of the Chinese Navy (PLA-N35), but also including the coastguard services and the so-called maritime militia.

Before reviewing these four elements, the first important idea is that the report highlights that in 2012, after years of reflection on the importance of maritime issues to advance China's (economic) development and its own security, and to consolidate China's own vision of its place in the world, CCP leaders emphasised that becoming a "maritime power" was essential to achieving national goals. What followed is known history, and today we could say that globally China is the world's leading maritime power, even if it is not yet the world's leading naval power.

Going into more detail in terms of the above elements, as far as shipbuilding is concerned, while the report highlighted that in 2010 China was the world's largest merchant shipbuilder, it also pointed to the need for China to seek economies of scale by creating mega-shipyards, focusing on quality rather than quantity. This has not only become a reality, but 36 is coupled with the fact that China is already building merchant and warships in the same shipyards, not only allowing the industry to operate more efficiently, but also the use of civilian technologies and production techniques for military shipbuilding, thereby maintaining the ability to circumvent sanctions aimed at military modernisation programmes.

In terms of its merchant navy, China controls a fleet of more than 5,600 ships, with a transport capacity of 270 million tonnes, making it the second largest merchant ship owner in the world (after Greece). China wants a significant part of its maritime trade to be carried by Chinese-owned ships, owned by Chinese companies (though not necessarily under a Chinese flag). In addition, China builds, manages and maintains a growing and very significant number of merchant ports all over the world (more than 100 ports in 63 countries37), and seven of the ten most important and busiest ones in the world are Chinese. Some analysts believe that this control of civilian ports around the world will eventually allow China to provide support (including maintenance) to military vessels when necessary. All this growth has happened with direct Chinese state support for the industry38, which gives it a clear advantage.

In relation to maritime infrastructures, a CSIS report39 (2021) warned of the possible loss of US leadership as a supplier of submarine cables in favour of China, highlighting that between 2004 and 2019 the former has gone from managing 50% of global internet traffic to 25%, and of course Xi Jingping planned "Digital Silk Road".40

Regarding the fishing component, China has by far the largest fishing fleet in the world, with between 200,000 and 800,000 vessels and responsible for half41 the world's catch, the growth of which is in large part due to state subsidies. China is the world's largest consumer of fish42, accounting for more than a third of the global total. As part of geopolitical aspirations, fishermen sometimes serve as paramilitary personnel (maritime militia), helping to entrench Chinese territorial dominance by expelling fishermen from other countries who challenge Chinese claims (especially in the South China Sea)43. Fisheries are an essential element of national food security objectives44, so the size and capacity of its fishing fleet and its protection are national interests.

The fourth, final and most important element of maritime power is the Chinese navy, its coastguard and the maritime militia. The Chinese navy is a more than significant part of China's maritime power,45 transforming in just a few years from an eminently coastal navy (near seas) to one capable of operating in far seas. Although the figures vary slightly depending on the sources consulted, it is a proven fact that China has surpassed the US46 in the number of naval units. The former has around 330 vessels (with forecasts of 400 by 2024 and around 440 by 2030), while the latter has around 300, though still at an advantage in terms of capacity and tonnage47.

However, notable qualitative Chinese advances include two operational aircraft carriers, and above all a third under construction (Fujian) with a displacement of 85,000 tons and electromagnetic catapults48 that put it, at least theoretically, at a technological level close to the Americans, and allow it to establish itself as a blue water naval power49. China has more than 80 world-class frigates and destroyers, increasingly capable and relevant amphibious units50 and a remarkable submarine force,12 of which are nuclear-powered (six with ballistic missile capability and six attack vessels), plus more than 46 conventional ones51. However, in other areas progress is less impressive, such as nuclear submarines and their high noise level, which some authors compare to 1970s Soviet submarines52. Russia53 has so far avoided transferring its acoustic silence technology, although this could change if its dependence on China were to increase significantly, which is not unthinkable in the current scenario.

Although the progress of the Chinese navy has been spectacular, managing to outnumber the US Navy, Inés Rodriguez54 reminds us that qualitative overtaking is still some way off.

China’s coastguard is the largest in the world, with more than 225 vessels of at least 500 tons displacement capable of operating on the high seas, and another 1,000 smaller vessels for coastal waters.

There is also the so-called "maritime militia"55, an entity with no clear official definition but is a kind of irregular force based on civilian vessels56 that supports oceanic defence normally integrated into the fishing community. Although it is the most unknown of China's maritime forces, and its members are theoretically civilians, the reality is that many of them are military personnel (active or retired), usually acting under military command, and whose missions and operations are designed by the Chinese state body. While there are no clear available figures, it is estimated to be the largest maritime militia in the world.

From an operational perspective, this militia is an instrument with a distinct advantage when interacting with foreign units, since while the latter are deciding how to act, it can interfere with their operations and report their location and activities to other Chinese forces57. Its role in the MSC is key, both in terms of defending the islets that China claims throughout the area and in protecting fishing vessels operating in non-Chinese waters (including in other countries' EEZs), and it is a key tool for both maritime surveillance and asymmetric actions in the grey zone framework.

The Chinese Coast Guard, together with the maritime militia, are instruments used for foreign policy objectives, and although theoretically not a means of warfare, they are used intensively in grey zone activities58, especially in relation to sovereignty claims in its nearby seas59 (Yellow, East, and South China Seas).

China claims sovereignty over almost 90% of the MSC (the nine-dotted line in Figure 3), arguing60 that it has traditionally been the fishing grounds of Chinese fishermen, making their right both historical and sovereign61.

Xi Jinping takes the helm for a new maritime China

China's current economy is based on the regular flow of goods along maritime routes (oil and gas, grain and raw materials coming mainly from the Middle East, Africa and South America), wherein the merchant fleet plays a key role, and on exporting Chinese products to foreign markets. The vulnerability of maritime connections (routes), in particular those through the Straits of Malacca, is key in the quest to be a genuine maritime power, which must also entail a corresponding naval strength62.

In an interpretation fully consistent with Mahan's theories, Xi believes that Chinese maritime power must be based on three basic elements: production, merchant and naval fleets, and overseas markets and bases.

Within this conceptual framework, Xi promotes China's transformation into a true maritime power for a number of complementary reasons. First is the idea of projecting national power beyond mainland China's territory, as it believes that within the perimeter of the first and second island chains it should be China that takes the lead, reconstituting its historical regional maritime pre-eminence. Second is the fact that China's seas are of fundamental interest to the Chinese population, given that China depends on imports for its growth, and therefore on the security of sea routes, and the surrounding seas are both a source of resources to feed its population (fisheries), and of potential energy and mineral resources. And to these reason can be added another of an emotional nature and in a way as a lesson learned: to be a great maritime power as a way to overcome the humiliations caused by the Western powers in the 19th century, and as a new form of relationship between great powers, in particular with the US63. The question is to use the tools with which China was humiliated, and not to be humiliated again.

In this whole spectrum of reasons64 for being a great maritime power, and the means to achieve it, in geopolitical terms and in his desire to be recognised as (the) great power, Xi wants China to be recognised65 as a responsible maritime actor (under the consideration that the US wants to contain China as a continental power, thereby preventing it from expanding its political and military influence to neighbouring littoral nations), and to protect maritime security interests66 by all means available (substitute what UNCLOS says for the historical rights supposedly acquired during the Ming, Yuang and Song dynasties).

While Xi initially wanted to avoid his country’s development as a maritime, and in particular a naval, power being paralleled by the perception of an increase in military tension, with its increasingly assertive policies, particularly in relation to Taiwan, and its growing and assertive naval capabilities, military tension, as seen in recent times, is inevitably growing.

And how does Xi say he wants to implement his idea of a great maritime power? The answer is through four67 main lines of action: establishing new high-level structures dedicated to maritime policy and strategy (to maintain its policy of "peaceful rise", meaning good relations with neighbours); developing naval capabilities to match or exceed those of its rivals in the region (in particular the US and Japan); restructuring civilian law enforcement agencies to have more options in territorial disputes; and last, demonstrating China's goodwill by taking part in regional forums, exercises, etc.

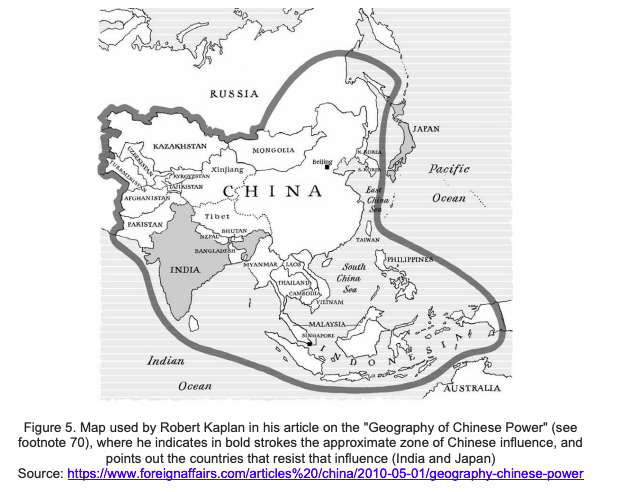

What about neighbouring countries? China's claims can be interpreted as a sort of Chinese version of the Monroe Doctrine, which the US declared in 1823 to dissuade European powers from interfering in the seas that the US considered its natural sphere of influence68. The country aims to reclaim maritime spaces of historical influence under a sort of "Asia for Asians" doctrine, seeking to turn the South China Sea into its own Caribbean. Although these pretensions are beginning to be taken on board by some countries in the region, they are clearly rejected by others such as Japan, South Korea and Australia, which is causing strong tensions in the region. Analysing this highly complex and multifaceted geopolitical reality is beyond the scope of this paper, although it is clearly a consequence of China's rise as a major maritime (and naval) power.

Final considerations: will China succeed?

The reality is undeniable: China has already become a major maritime power. It excels in all the elements that constitute this power, including its shipbuilding capacity, its merchant fleet and its fishing fleet, to which we can add an outstanding coastguard and maritime militia, and a naval force that is increasingly powerful and rapidly approaching US Navy levels, which has remained unchallenged for the past 75 years. This rise as a maritime power has not come at the cost of its weakening as a continental power, but has been complementary. China remains a major continental power, with growing influence in Mackinder's heartland, particularly over Russia and the Central Asian countries, making it the first hybrid continental and maritime great power.

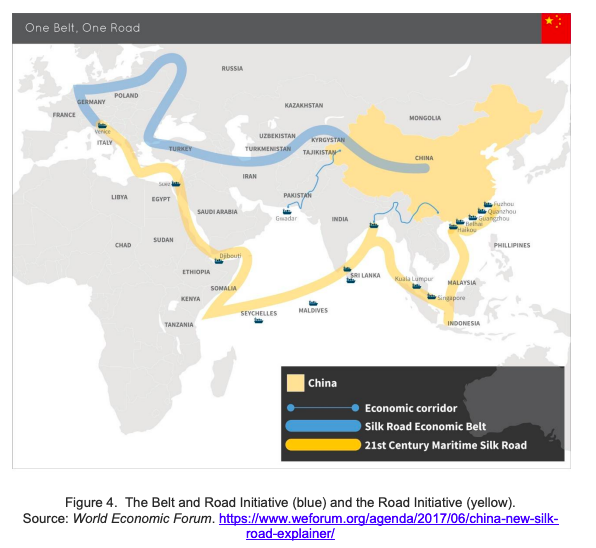

Then there is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)69, the Belt part of which seeks to create overland infrastructure linking China to Europe via Central Asia, and the Road part of which seeks a maritime silk road linking China to Southeast Asia, Europe and Africa, with ports and bases in the Indian Ocean. To this effect, we have a hybrid combination, a Belt aligned with Mackinder's postulates, and a Route that could well have been drawn by Mahan himself. The initiative, however, is progressing intermittently, and not as quickly or as completely as China would have liked, due to a number of problems, including mistrust of China by several of the countries involved, especially the "debt trap70".

Nonetheless, while the debate from a Western perspective revolves around whether China is a continental power or a maritime power, and whether as a maritime power it will be able to dethrone the US hegemon, from a Chinese perspective what it theoretically seeks is to restore the traditional Chinese maritime order71 in the framework of a sort of return to the Great Middle Kingdom (continental power). In this vision, as can be seen in the map in figure 5), states such as South Korea and Vietnam do not want to be under Chinese influence, to once again become tributaries under the umbrella (but not territorial dominion) of the new Great Middle Kingdom.

Let us not forget that in the various documents on Chinese maritime strategies and policies, one central element prevails over the others: the defence of Chinese rights and interests at sea. China is ready to defend its alleged rights, which it considers historical, over certain maritime spaces (in particular the MSC), where it intends to exercise active sovereignty both by exploiting resources (minerals, hydrocarbons, fisheries) and by exercising control over a sea that it considers its own. Along with this is China’s intention to regain its ascendancy over other areas, such as its exit to the Indian Ocean through Malacca, which it considers its historical space, and which today is a point of critical vulnerability for its trade and therefore for its own economy and development, and is where our own interests and China’s converge.

Kaplan compares China's maritime development with that of the US 100 years ago, considering that China has no land-based expansionary aspirations and will have no problems with its neighbours since it has achieved stability in its land borders, allowing it to look out to sea72. But while it currently has no enemies on the mainland, the situation is one of limited stability, and while not foreseeable in the short term, its land borders could quickly become vulnerable, as they did in the 15th century in the years of admiral Zheng to the Mongol threat from the north.

In a similar vein, Ignacio Castro73 likewise considers that Chinese geopolitical thinking does not have hegemonic aspirations, supporting the idea that it only seeks a relevant place in a new harmonious order and to protect its aforementioned "rights and interests", and does not really want a confrontation with the US. This, however, is not an easy situation to manage at the moment given the Taiwan issue.

These interpretations are very consistent with what we mentioned previously about official Chinese documents and statements on the country’s peaceful rise. Perhaps the way in which this maritime development is being carried out, through a kind of calculated and deliberate "strategic ambiguity"74, as advocated by Sarah Quan among others, is what is generating uncertainty and mistrust in neighbouring countries and in particular in the US. By not allowing the underlying disputes to be resolved, China is being permitted to continue expanding its sovereignty, despite the fact that its intentions and the scope of this expansion remain unclear.

Delving deeper into history and geography, and although the situations are not entirely similar, the historical examples of France and of Wilhelmine Germany in the early 20th century are significant. The former was also a power with continental and maritime potential, but whose land borders with Germany did not allow it to become a true maritime power, and the latter, though clearly disadvantaged by geography, catastrophically attempted to follow Mahan's postulates and become a great naval power to challenge and overcome the British maritime hegemony of the time, in what has come to be called the " Tirpitz trap”75 after the dispute between a great continental power in Europe in 1914 and the great maritime power, the UK 76. This example has been used by Chinese Colonel Xu Wiyu to subtly warn that China should not follow the example of Imperial Germany and avoid the Thucydides trap, albeit avoiding explicit parallels with the current situation between China and the US.77 . Anecdotally, despite Xu's caution, Graham Allison, author of "Destined For War: Can America and China escape Thucydides' Trap?", on the Thucydides ' Trap as applied to China and the US, wrote the foreword to Xu' s English translation of the work with a clear reference to China.

In this scenario of uncertainty about the consequences of China's maritime rise, there are voices that consider that China may be running out of fuel before it even reaches port, that it may be a power that has already reached its zenith and is beginning its decline without having caught up with the US. In this framework, some authors78 argue that the real danger is actually not in the Thucydides trap, where the declining power provokes war to prevent the rise of the rising power, but the peaking power trap, where the revisionist power, without having overtaken the dominant power, is aware that it has reached its zenith and is beginning its (relative) decline, causing it to act in desperation in an attempt to reach the dominant position before time runs out, thereby seeking to avoid having to bear the painful consequences of its decline79.

This possibility80 could be one of Xi's greatest fears: to continue to pilot China's rise to end up becoming the president of a declining China. Instead of the 21st century Stalin or Mao, he would thereby end up being the Chinese Brezhnev, catalysing the gradual erosion of the values he holds so dear81.

Today’s reality is that China has become a major maritime power, seeking to impose its maritime order in both its regional sphere, in what it sees as its historical zone of influence, and globally, needing to secure maritime lines of communication. Factors such as favourable but not so advantageous geography, possible economic stagnation and demographic decline, among others, could mean that China may not be unable to navigate the course it has drawn on its chart and even its arrival in port may be compromised, with the unforeseeable consequences this could entail.

Abel Romero Junquera*

Navy Captain (reserve)

IEEE Analyst

Referencias:

1 https://www.ft.com/content/ebd9b4ae-296f-11e2-a604-00144feabdc0

2 TOBIN, L. Underway. Beijing's Strategy to Build China into a Maritime Great Power. US Naval War College Review. Vol. 71. No. 2 Spring 2018, p 16-17. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol71/iss2/5/

3 https://www.brookings.edu/articles/xi-jinping-and-chinas-maritime-policy/

4 YOON, S. Implications of Xi Jinping 's "True Maritime Power": Its Context, Significance, and Impact on the Region. Naval War College Review. Vol. 68. No. 3, Summer. Article 4 (2015) https://digital-commons. usnwc.edu/cgi/ viewcontent. cgi?article=1220&context=nwc-review

5 https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/library/news/china/2013/china-130731-pdo05.htm

6 TILL, Geoffrey. Seapower. A guide for the Twenty-First Century. Second Edition. Routledge, New York. 2009.

7 Ibid. p. 20.

8 Ibid. p. 26. Till considers (p. 23) that to avoid ambiguity the terms "maritime power" and "seapower" can be used interchangeably, which we will do in this paper.

9 WEI, Z. and AHMED, S. A general review of the History of China's Sea-Power Theory Development. Naval War College Review. Vol. 68. Nº 4 Autumn. Article 8 (2015). https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc- review /vol68/iss4/8/

10 TOBIN, L. Op. cit., 2018, pp. 16-48

11 BAQUÉS, J. The fundamental lessons of Mahan's work: from geographical determinism to the commercial spirit. Revista IEEE, nº 18 (November 2018). Page 109, footnote 1. https://revista.ieee.es

/article /view/166/265

12 BAQUÉS, J. (2019) The sea as a catalyst for geopolitics: from Mahan to the rise of China. Journal International Security Studies, Vol.5, No.1 (2019), pp. 119-139. phttp://www.seguridad internacional.es/resi/ index.php/revista/article/view/117/203

13 VAQUEZ, G (2022). Alfred Mahan's influence on Chinese naval doctrine. University of Navarra. https://www.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/influencia-de-alfred-mahan-en-la-doctrina-naval-de-china

14 Essentially with Russia and India, with which it currently has good, or at least civil, relations, but which Beijing considers not to be entirely trustworthy.

15 Both its exit to the western Pacific through the first chain of islands and, above all, to the Indian Ocean through the Strait of Malacca.

16 BAQUÉS, J. Op. cit., 2019, p. 137.

17 MITCHELL, M. (2020) Using the principles of Halford J. Mackinder and Nicholas JohnSpykman to reevaluate a twenty-first-century geopoliticalframework for the United States. COMPARATIVE STRATEGY 2020, VOL. 39, NO. 5, 407–424, p 411. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2020.1803709

18 Mackinder, in his work "The Geographical Pivot of History" (1904), and in later writings, argued that whoever dominates the Heartland will dominate the World Island- which consists of Eurasia plus Africa - and thus the world.

19 BAQUÉS, J. Op. cit., 2019, p. 121.

20 MITCHELL, M. Op. cit., 2020, p. 412.

21 KAPLAN, R. (2012). The Vengeance of Geography’. Geography shapes the destiny of nations. RBA libros, SA, Barcelona. First edition (2017), fifth reprint (2022). P. 242.

22 At the time, the Arctic was an icy barrier rather than a sea front, preventing Russia from setting sail but also protecting it from maritime powers. This is still the case today, although to a lesser extent, as a result of climate change and the progressive warming of the Arctic.

23 Nationally renowned authors such as Felipe Sahagún https://www.infolibre.es/ videolibre/como-lo- ve/felipe-sahagun-rusia-acabar-convirtiendo-vasallo-ordene-china_1_1222193.html or Jose I. Torreblanca https://www.cope.es/programas/herrera-en-cope/noticias/torreblanca-politologo-enorme-fracaso-rusia- convertir-vasallo-china-20220315_1969153

24 These voyages served to consolidate the tributary system, with states in North, Southeast and South Asia, with China at the top. These pledged allegiance to China, accepting its diplomatic requirements, sending emissaries with tributes to the Imperial Court and receiving favours and gifts in return. The system provided access, protection and status to both parties. There was no direct control or domination by China over its tributaries, but within the framework of Confucianism it was understood as an accepted set of hierarchical roles to preserve harmony and ethical conduct. This system operated for 500 years, until the mid-19th century. https://medium.com/ @andrewsingerchina/chinas-original-maritime-influence-zheng-he- s-ocean-voyages-during-the-ming-dynasty-e28650fb9284

25 YOON, S. Implications of Xi Jinping's "True Maritime Power": Its Context, Significance, and Impact on the Region". US Naval War College Review. Vol. 68. No. 3 Summer 2015, pp 40-63. p. 48. https://digital- commons.usnwc.edu/ nwc-review /vol68/iss3/4/

26 https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/china-zheng-he-naval-explorer- sailed-treasure-fleet-east-africa

27 KAPLAN, R. Op. cit., 2012, p. 243.

28 BAQUÉS, J. Op. cit., 2019, p. 137.

29 To these objectives can be added the ability to project forces into the Indian Ocean, in an attempt to break the US defensive arc, which stretches from the Aleutians through Japan to the Philippines, by regaining sovereignty over Taiwan, which would allow it unrestricted access to the Pacific.

30 YOON, op. cit., 2015, pp. 2 -3.3

31 WEI and AHMED op. cit., 2015, pp. 2-3.

32 Sea Lines of Communication

33 LATHAM, A. Mahan, Corbett, and China's Maritime Grand Strategy. (24 August 2020). https:// thediplomat.com 2020 /08/mahan-corbett-and-chinas-maritime-grand-strategy/

34 McDEVITTt, M. Becoming a Great "Maritime Power"; A Chinese Dream. June 2016. CNA (Analysis and Solutions). https://www.cna.org/reports/2016/china-becoming-a-maritime-power

35 PLA-N. People's Liberation Army - Navy. It is the Chinese navy, the naval component of the Chinese Armed Forces.

36 https://asiatimes.com/2023/02/us-navy-laments-chinas-shipbuilding-supremacy/

37 It is estimated that China controls one tenth of Europe's port capacity, https://thediplomat.com/ 2021/12/chinas-growing-dominance-in-maritime-shipping/

38 https://www.csis.org/analysis/hidden-harbors-chinas-state-backed-shipping-industry

39 Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a think-tank based at Georgetown University in Washington DC https://www.csis.org/

41 https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/17297/china-fishing-fleet

42 https://chinapower.csis.org/china-food-security/

43 URBINA, I. How China's expanding fishing Fleet is depleting the World's Oceans (2020). https://e360.yale.edu/ features/how-chinas-expanding-fishing-fleet-is-depleting-worlds-oceans

44 McDEVITT, op. cit., 2016, pp. 100-109.

45 AXE, David. "Has China become the World's Greatest Maritime Power?" The National Interest (30-12- 2021). https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/has-china-became-worlds-greatest-maritime-power-198680

46 The US has approximately 300 vessels for high-intensity "Principal Surface Combatants" operations, of which 67 are nuclear submarines, and 122 vessels with high-intensity capabilities (11 aircraft carriers, and 111 escorts). IISS Military Balance 2023data, accessed 22 June 2023. Likewise, the 29 Nov 2022 report to the US Congress on China's military power details the evolution of China's military assets, including naval assets. Available at https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND- SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF

47 CHILDS, Nick. Asia-Pacific. Naval and maritime capabilities; the new operational dynamics. Chapter 3, "Asia-Pacific Regional Security Assessment 2023". IISS, p 62-89. https://www.iiss.org/publications

/strategic-dossiers/asia-pacific-regional-security-assessment-2023/

48 Capable of launching heavy aircraft, including early warning aircraft (such as the KJ-600, still under development). https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/our-first-clear-look-at-chinas-kj-600-carrier-based- radar- plans-nose

49 Blue watersare essentially oceanic waters and open seas. Brown waters (navigable rivers and their estuaries) andgreen waters (coastal waters, harbours and bays) are also defined. US 2010 Naval Operations Concept (p. 8). https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/NavalOperationsConcept 2010

.pdf

50 FANELL, James. “China: Growing and Going to Sea". Proceedings, May 2023. https://www.usni.org

/magazines/ proceedings/2023/may/china-growing-and-going-sea

51 Data from IISS (International Institute for Strategic Studies), Military Balance 2023, accessed 22 June 2023.

52 Russia greatly improved its noise level with the Akula class submarines in the 1980s, while the Americans had already lowered their noise level with the Permit class as early as the 1960s.

53 SWEENEY, Mike "Submarines will reign in a war with China". Proceedings, March 2023. https://www.usni .org/ magazines/proceedings/2023/march/submarines-will-reign-war-china

54 RODRIGUEZ, Inés. The role of the Asian giant at sea: the rise of China as a naval power. IEEE. Opinion Paper 57/2023, 2 Jun 2023.https://www.ieee.es/contenido/noticias/2023/06/DIEEEO57 2023_INEROD China.html

55 McDEVITT, op. cit., 2016, pp. 62-83.

56 https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/21/

57 ERIKSON, A and KENNEDY, C. China's Maritime Militia. What is it and how to deal with it. Foreign Affairs. 23 June 2016. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2016-06-23/chinas-maritime-militia

58 For more on the idea of "grey zone", of particular interest is the definition of this concept by Josep Baqués, in his IEEE research paper 02/2017, available at: https://www.ieee.es/Galleries/file/docs investig

/2017/DIEEEINV02-2017 ConceptoGaryZoneJosep Baques.pdf

59 AXE, D. Op. cit., 2021

60 In this regard, China is becoming adept at using legal arguments without a solid basis to intimidate other states, and with the support of its coercive forces, particularly its maritime militia, it achieves maritime objectives on the basis of fait accompli policies without escalating to the use of military force, in what has come to be known as "adverse possession". This stratey is very clearly seen in the MSC. These practices are dangerous, not only because they go against international maritime law (UNCLOS), but also because the same practices, this time based on the regular presence of Chinese fishing fleets in distant waters, could be used in other maritime areas of the world where China currently fishes, high seas areas or waters of other countries (Africa, South America, etc.), which could include exclusive economic zones, thereby conceding sovereignty to it. https://www.maritime-executive.com/index.php/editorials/china-s-maritime- strategy-to-own-the -oceans-by-adverse-possession

61 To some extent, China seeks to argue that the presence of Chinese fishing vessels in distant waters on the high seas would give them a degree of sovereign control over those waters and their resources. An example of this is China's positions on the rights of non-Arctic peoples to resources (hydrocarbons, gas, minerals and even fisheries) in the Arctic.

62 YOON, Op. cit., 2015, pp. 3-4

63 YOON, Op. cit., 2015, pp. 4-8

64 China seeks to exploit a calculated ambiguity to push its historical claims over disputed waters with other countries, such that based on Admiral Zheng He's voyages during the Ming dynasty, it wants to impose new rules based on these historical precedents, far removed from what current laws and principles prescribe. Rather cleverly, and using a sort of "salami tactic", China's historical claims are being protected by civilian security agencies rather than military forces, helping to keep the crisis level below the threshold of confrontation – clearly in the grey zone.

65 YOON, Op. cit., 2015, pp. 8-10

66 claims over certain islands, in particular in the South China Sea, are seen as territorial claims that could be assimilated to those it maintains over Tibet and Taiwan);

67 YOON, Op. cit., 2015, pp. 11-15

68 YOON, Op. cit., 2015, pp. 17-20

69 https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-bri

70 China is accused of using the so-called "debt trap", which involves lending money to the country where the infrastructure has been built for its implementation, but when the country (especially the poorest ones) cannot pay back the loans, China takes sovereignty over the infrastructure. This is compounded by a dismal human rights record in this initiative. https://www.news.com.au/finance/economy/world-economy/chinas- belt-and-road-plan-projected-to-have-massive-economic-benefits-but-there-are-are-major-concerns/news

-story/bafe7b546969d74047c1e6bb cdc926579c

71 YOON, Op. cit., 2015, pp. 17-18

72 KAPLAN, R. The Geography of Chinese Power. How far can Beijing reach on land and at sea. Foreign Affairs May/Jun 2010. Vol 89, No. 3. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2010-05-01/geography- chinese-power

73 CASTRO, I (2014). The three major pieces of the geopolitical chessboard in the age of globalisation: the cases of the US, Russia and China. IEEE. https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs opinion

/2014/DIEEEO96-2014_TableroGeopolitico EraGlobalizacion_JLCastroTorres.pdf

74 QUAN, S (2019). China's Maritime Grand Strategy. Brigham Young University. Undergraduate Honors Theses. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1105&context= studentpub_uht

75 In the context of disputes between a continental power (Germany) and a maritime power (the UK), the Germany of Wilhelm II, under the leadership of Admiral Tirpitz, tried to build a large naval fleet to confront the British, hegemonic at the time, resulting in the well-known failure, mainly for geographical reasons, particularly the lack of clear exits to the sea. Some authors consider that the construction of that impressive fleet detracted economic resources that could have been used to equip the land force, in line with what Chancellor von Bülow said as early as 1908, that Germany could not weaken its land army since its fate would be decided on land.

76 SOTCKER, J (2023). Tirpitz's Trap. US Naval War College Review, Volume 76, Number 1 (Winter 2023). https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol76/iss1/8/

77 SOTCKER, J (2023), op cit. pp 1-2.

78 BEKLEY, M and BRANDS, H. China is a declining power and that's the problem. Foreign Policy, 24 Sept 2021. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/09/24/china-great-power-united-states/

79 In terms of resources and economics, China has a significant lack of water and energy, which also translates into a clear relative slowdown of its economy, from 14% growth in the 2000s to 6% in 2019, in a trend towards single-digit growth that promises to be the trend in the coming years. The centralisation of power that Xi is promoting does not help, and is also likely to have negative consequences for China's economic prosperity. On top of all this, there is the demographic problem, as it is estimated that between 2020 and 2050 China will lose 200 million citizens of adult age (able to work), increasing the number of retired people by a similar number, which will lead to enormous social and health care costs.

80 This scenario could lead China to feel enclosed, as happened with Japan and Germany in World War II, and could push leaders, in this case Xi Jinping, to opt for aggressive decisions in the coming years, such as the use of force to regain Taiwan, thereby opening China's door to the Western Pacific, a matter that deserves a specific analysis, which is not the subject of this paper.

81 WESTAD, O. "What does the West really know about Xi's China? Why Outsiders Struggle to Understand Beijing's Decision-Making. Foreign Affairs, June 13th 2023. https://www.foreignaffairs.com /china/what- does-west-really-know-about-xis-china