From Africa to the Gulf; China redirects its energy strategy

- Angola's oil production challenges

- Global energy market transformation

- China's emergence on the energy scene

- Strategic strengthening between China and the GCC

For years, China has been gaining ground in Africa as the US withdrew from the region, leaving a significant vacuum in Western influence over this "final frontier". Now, however, that expansion based on soft power and oil-backed loans is losing steam. Various think tanks point out that China is increasingly opting for Arab oil rather than African crude.

As the media outlet Al Arab recalls, in 2002, with the end of Angola's 27-year civil war, the central African nation implemented the so-called "Angola Model", obtaining oil-backed loans from China to finance the construction of roads, hydroelectric dams, railways and other public services. However, this strategy did not last.

According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Angola has slipped down the list of China's top crude oil suppliers, as Beijing increasingly turns to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, Russia and other Asian countries. While in 2010 Angola was China's second largest oil supplier, preceded only by Saudi Arabia, last year it had fallen to eighth place, as reported by the South China Morning Post (SCMP).

The Angolan Model worked well in its early years. According to Boston University data cited by SCMP, between 2000 and 2022, Angola borrowed a total of 45 billion dollars from China, part of which was repaid with oil. However, when oil prices collapsed in 2014, at the height of the shale boom, Angola was forced to pump much more oil to pay off its debt to China, illustrating the risks of easy money from Beijing.

Angola's oil production challenges

Angola, along with other African oil producers, has struggled to attract investors to develop its oil fields and build infrastructure. Despite the initial enthusiasm of major oil companies such as BP, Exxon and Chevron for the country's vast deposits, obstacles remain, including unfavourable tax regimes, corruption and, in some cases, a lack of resources to secure assets. Angola has repeatedly failed to meet Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) production quotas.

Currently, Angola is one of OPEC's smallest producers, with output of just 1.15 million barrels per day in November, representing 0.3% of the organisation's daily production of 38.19 million barrels. Angola's production was 1.66 million barrels per day when it joined OPEC in 2007, and peaked at 1.88 million barrels per day a year later. Since then, production stabilised at around 1.80 million barrels per day in 2015 before falling sharply in the following years. Angola's current production level is slightly above OPEC's target of 1.10 million barrels per day.

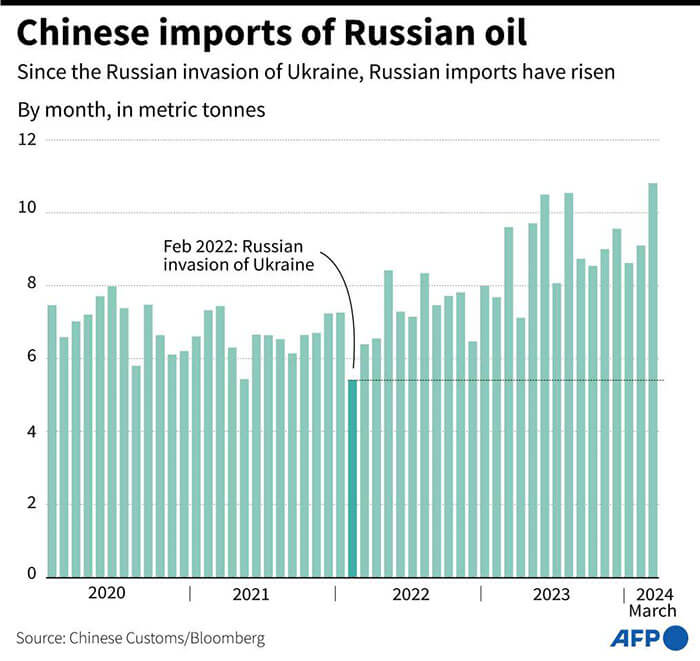

As energy news portal Oil Price reports, relations between Angola and OPEC reached a high point last year when OPEC allowed the United Arab Emirates to increase its output by 200,000 barrels per day to 3.2 million barrels in 2024, but slightly reduced Angola's quota for 2024 in line with its own production decline. Meanwhile, China has increasingly focused its attention on more predictable production infrastructure in the Gulf states and Russia. According to the Carnegie report, "imports have increased by more than 40 per cent for almost all of China's major oil trading partners in Asia except Iran, whose oil is shipped through countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Malaysia".

As in Angola, ageing oil fields have been a major reason for declining production in many African producers, especially Nigeria, but also in smaller producers such as South Sudan, whose oil development is in a constant state of ups and downs, most recently due to the civil war in neighbouring Sudan. With the focus on offshore locations such as Guyana and Namibia, traditional African players are lagging behind. With the exception of the discovery in Angola's offshore Block 15 in 2022, Exxon has kept a low profile in Africa.

Global energy market transformation

China, with a strong focus on the GCC, has been actively pursuing energy ties with Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman and Qatar. Last year, according to data published by China Daily, China imported nearly 200 million metric tons of crude oil and 18 million tons of liquefied natural gas from the GCC. This represented a third of China's total oil imports and about a quarter of its total natural gas imports.

As the European Council on Foreign Relations' policy report “East meets middle” points out, it is not just about fossil fuels. China is focusing on ties with the GCC in the renewable energy sector, as well as in the nuclear field. Huang Mingang, chief economist of China National Nuclear Corporation, told China Daily that Beijing "leverages the nuclear industry's comprehensive supply chain and technical service capabilities to provide Arab countries with integrated nuclear power solutions and full life-cycle services".

China's new relationship with Saudi Arabia and the UAE is driven in part by a structural shift in global energy markets, particularly the shift of the centre of gravity of global energy demand towards Asia and China. This shift not only challenges the core of the US-Gulf ‘energy-for-security’ relationship, but also alters patterns of geo-economic dependencies and calls into question the future denomination of oil trade in dollars.

In 1945, a meeting between then US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Saudi King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud aboard the USS Quincy was the first step in an alliance based on a stable supply of low-cost oil in exchange for US security guarantees. For decades, oil has been sold in dollars and the large revenues derived from its sale - "petrodollars" - were largely recycled into the US economy. This mechanism played an important role in strengthening the American economy after World War II and in the dollar's international dominance. In return, the US became the main security partner of the Gulf states and the cornerstone of the regional security architecture in the Middle East.

But in the last decade, profound transformations in energy markets have challenged this ‘energy for security’ arrangement. Following the shale gas revolution, US oil imports from Saudi Arabia fell fivefold between 2012 and 2022. The US economy remains dependent on international energy prices, but this development, coupled with the prospect of global energy transitions, has fuelled a debate in Washington about the need to diminish US security involvement in the Middle East. This debate is having concrete repercussions: for example, in 2019, Donald Trump refused to intervene after an Iranian attack on Saudi oil facilities in Abqaiq and Khurais, which was seen as a betrayal in Gulf capitals.

China's emergence on the energy scene

Moreover, China's rapid emergence over the past two decades as the Gulf states‘ largest energy customer radically changes the landscape of these states’ core economic interests. It also raises new questions about whether this new situation could lead to greater Chinese political and security involvement in the Gulf in the long term.

In 20 years, China's energy imports increased fifteenfold, and the country has been the world's largest oil importer since 2016. The Gulf alone accounts for half of China's hydrocarbon imports. As a result, China's share of total GCC energy exports jumped from 5% in the early 2000s to more than 20% in 2023. This share is projected to continue to increase over the coming decades. While GCC oil imports to other Asian countries, especially India and Southeast Asian countries, are also expected to increase rapidly in the coming decades, they are unlikely to replace China as the main importer.

The development of a long-term relationship between China and the Gulf countries has become crucial for the economic security and prosperity of all concerned. Both sides have increased their joint investments along the energy value chain, from exploration and exploitation of oil fields to investments in storage, refineries, petrochemical industries and the signing of long-term supply agreements. In 2021, Aramco CEO Amin Nasser declared that the Chinese market would be the company's top priority for the next 50 years.

Strategic strengthening between China and the GCC

For the Gulf states, strengthening their relationship with China is a strategy to maintain their central position in the world economy and retain the geo-economic leverage it gives them, especially in times of global energy transitions. This objective explains why some of Saudi Arabia's recent investments in China's refineries have been heavily subsidised. Many of these investments, from the outside, appear to lack an economic rationale and instead seem designed to deepen China's dependence on Gulf oil.

From China's perspective, heavy energy dependence on the Gulf is, in fact, changing Beijing's perspective on the region and forcing it to pay greater attention to stability in the Middle East. This development has triggered debates among Chinese scholars on whether Beijing should devote more diplomatic and military capital to the region. Over the past decade, China has sought to reduce its energy dependence on individual countries such as Saudi Arabia by diversifying its suppliers to Iraq, as well as Angola, Brazil and Venezuela. However, Gulf producers look set to remain key energy partners for China, as their price advantage in oil and gas production means they will outbid other producers that could be undermined by the green transition.

In the longer term, global energy transitions are likely to shift the energy relationship between the Gulf states and China in favour of the latter. The evolution of global energy markets has already limited the impact of geopolitical tensions and conflicts on world oil prices. The Abqaiq-Khurais attack in 2019 and, more recently, the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea have not triggered the kind of price increases that would have been likely just a few decades ago. Chinese policymakers may consequently decide that access to cheap oil is no longer an existential issue, as was glimpsed, for example, with China's hesitation to invest in Aramco when it went public in 2019. It is therefore unlikely that the new energy interdependence between the Gulf and China will automatically lead to greater Chinese involvement in the region's geopolitics and security in the same way it did for the US in the 20th century.

Overall, the picture that emerges of China's relations with the UAE and Saudi Arabia is one of a growing but still limited and largely transactional partnership. Despite some notable achievements, these relations still struggle to match the depth of the region's decades-long ties with the West. However, both China and the Gulf states have an interest in seeing this relationship continue to grow in depth and breadth in the face of an increasingly multipolar and competitive world.