Erdogan opens the door to the European Union for refugees

The air attack launched on Thursday night by Bachar al-Asad's army on a Turkish checkpoint near Idlib is beginning to have consequences. Following this episode, in which at least 33 Turkish soldiers have been killed and another 35 injured, the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan has decided to seek allies. It has looked to NATO, to the United States... and also to the European Union.

So far, Brussels' official position on the Syrian conflict has been one of non-interference and respect for the rules of international law, although it is true that some of its most prominent members, such as France and, before the Brexit, the United Kingdom, have taken some action themselves. Nevertheless, Erdogan is seeking at least a formal declaration of support for his cause from the Community institutions.

How does he intend to achieve this objective? By applying pressure. Turkey has decided to open its borders to allow the passage of refugees onto EU soil. On the one hand, the south-east border with Syria will remain open for three days, according to official sources, so that the Syrian refugees waiting there can enter Turkish territory. On the other hand, representatives of the Turkish administration have stated that they will not stop those refugees who try to cross the border into the EU with Greece and Bulgaria. The security forces have been expressly asked not to prevent the refugees from leaving.

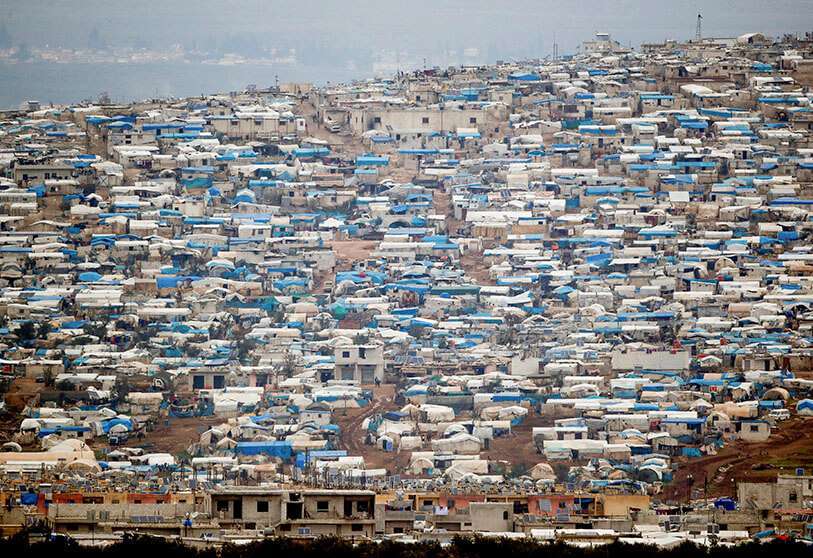

Under agreements ratified by Brussels and Ankara in 2016, the country of Anatolia has been acting as a checkpoint against the incessant flow of refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and other countries in exchange for financial compensation. However, most of the Turkish refugee camps are on the edge. The country is already home to more than three and a half million. In addition, since last December, the UN estimates that about one million have been forced to leave their homes in the Idlib region. Most of them have left in a caravan to the north, precisely in the direction of Turkish territory.

Although Erdogan had already threatened to release the flow of refugees into the EU on several occasions, this is the first time he has made a firm decision. The official Turkish news agency Anadolu published several videos this Friday morning showing a fleet of buses travelling west with refugees on board, their destination being the border with Greece.

The caravan was chartered by the Syrian community in Istanbul. There are also images of large queues of people ready to board the ferries to the Greek island of Lesbos from the ports in the Turkish border province of Çanakkale.

What can the Turkish President hope to achieve? Realistically, it is not a question of military support, since the EU per se does not have its own armed forces. Equally, it is unlikely that the Member States, at their own risk, would be prepared to become unilaterally involved in the Syrian hornet's nest. That route is more likely to be investigated through NATO. At best, Erdogan could succeed in changing the EU's position from non-intervention to explicit support for Ankara. This may not seem much, but it would be a fairly important step.

At the moment, neither the European Council nor its president, the former Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel, have publicly stated their position on Erdogan's manoeuvre. The Greek country, in its own right, has already reinforced patrols on its territory at checkpoints near the border. It is to be hoped that Bulgaria will take similar measures.

With the agreements between Brussels and Ankara, many refugees have, over the past few years, chosen to try to enter the European Union illegally and using the means provided by human trafficking organisations. The Mediterranean routes, both through the Straits of Gibraltar, through the central area (between the Libyan coast and Italy) and through the eastern area - precisely on the Greek coast - have become very busy roads that have claimed the lives of thousands of people.

To manage this, the EU had set up a rescue operation in the waters of the Mediterranean known as Operation Sofia, which was replaced just a few days ago by another deployment aimed at ensuring the international arms embargo on Libya. During the interval in which it was active, Operation Sofia did not prevent many refugees from reaching European shores.

The problem is that the Brussels institutions, which usually take most of their decisions by consensus, have not been able to articulate a unitary policy for the management of refugee flows. The quotas that were tried to be established were not respected, some countries like Hungary closed their borders and only Germany has carried out a consistent reception policy.