Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso: Redefining alliances in the West African geopolitical landscape

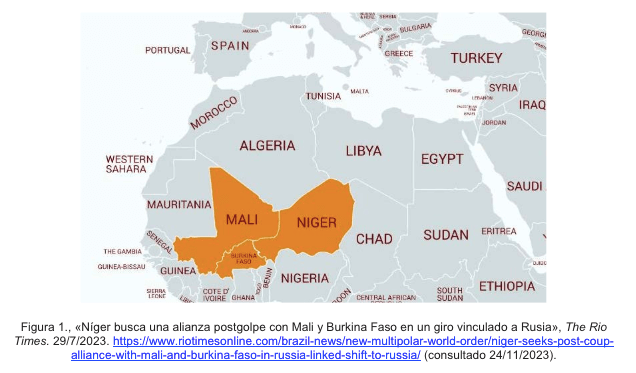

Motivated by the growing presence of terrorist groups and a succession of coups d'état in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, West Africa is facing a geopolitical reconfiguration. As a result of these coups, the military juntas that have seized power have shown their willingness to distance themselves from traditional alliances and ties with Western powers. The reason for this is that they are blamed for the failure to combat the problems of instability and insecurity facing the region. Due to this factor, the US and the EU have seen their presence and influence in the region greatly reduced. For its part, Russia appears as a possible new ally and the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) threatens the future of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The future geopolitical landscape of West Africa depends on these alliances and their external supporters. This paper will analyze the situation in these three countries and the possible consequences of the new alliances.

- Introduction

- Similarities between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso

- Presence of France and the United States

- Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger’s own initiatives

- Russia as an alternative for foreign aid to emerging governments

- Threats of Russian presence to the West

- Conclusions

This document is a copy of the original published by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies at the following link.

Introduction

Since 2020, six coups d'état have taken place in West Africa. Two in Mali (2020, 2021), two in Burkina Faso (2022, 2022), one in Niger (2023) and one in Guinea (2021). The panorama of notable instability is accompanied by a strong military presence in the region.

Corruption, economic mismanagement, the rampant rise of jihadism and the inability of the regional governments to deal with presented challenges are some of the factors that have encouraged political and social tensions that have been reflected in the mentioned coups d'état.

The countries of the Liptako-Gourma region (Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger) have been more proactive than Guinea. They have taken their own initiative and decided to unite in coalition to resolve the precarious situation in Western Africa, abandoning established relations and alliances to create new ones that are the subject of analysis in this paper.

Similarities between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso

These three countries share much more than a border. First, they share a colonial past marked by the French presence. All three were part of Afrique Occidentale Française, experienced its influence of culture and administration, and gained independence in the same year, 1960. To this day the relationship of these countries with France is still quite strong, both politically and economically. The clearest example of this is the use of the CFA franc1 as the national currency in all three countries. A currency linked to the euro, which is essentially controlled by France and has been described as a form of monetary colonialism2 by some economists3.

Secondly, the three countries enjoy great cultural diversity within their borders, where communities of different ethnicities, religions and languages coexist. However, within this diversity there is a predominant Muslim influence, whose origins lie in the arrival of the Tuaregs in the 12th century and which is still present today with a certain radicalization by terrorist groups.

Third, these countries share similar economic difficulties. High poverty rates, poorly diversified economies and a high dependence on agriculture or raw materials. Their economies, as a consequence of the colonial period, are more focused on the exploitation and export of raw materials than on manufacturing. For example, Niger is highly dependent on the exploitation and export of uranium, gold or oil mines.

Fourthly, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso suffer from great political instability. Continuous changes in power, coups d'état, widespread corruption and lack of unity with neighboring countries in the fight against shared problems are the result of the failure of the established political systems. In Mali, Colonel Assimi Goïta has led two coups d'état in the last four years. The first in August 2020 and the second in May 2021. In Burkina Faso, there have also been two coups d'état, the first in January 2022 and eight months later the second in October 2022, which brought Captain Traoré to power. In Niger, the last coup d'état took place on July 26, 2023, with the Nigerian army overthrowing President Mohamed Bazoum.

These coups have had multiple consequences in economic matters and relations with neighboring countries and powers present in the area. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), of which the three countries are members, has applied various sanctions, interrupting diplomatic and trade relations with them, and the African Union (AU) has suspended the three states from the organization.

Finally, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger share a huge regional security problem, caused by the high presence of terrorist groups, especially Islamists. This has a direct and indirect negative influence on the other factors mentioned above.

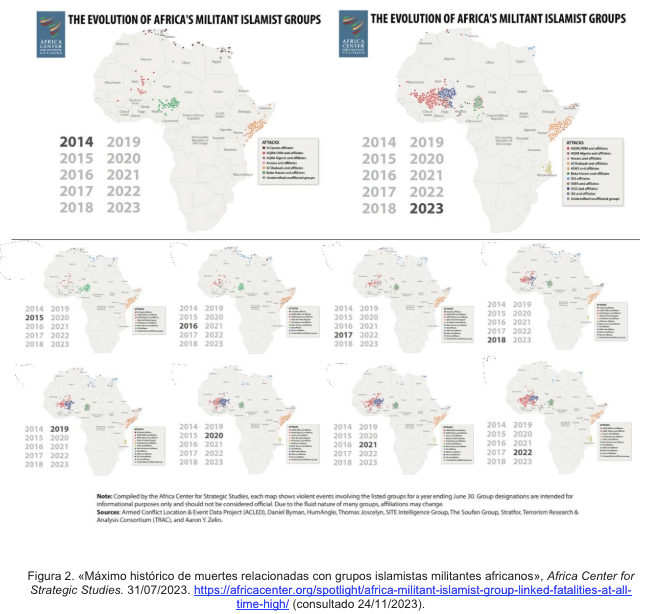

The beginning of this increase in terrorism, which was exploited by jihadist groups to extend their presence in neighboring countries and take over the region, can be traced back to the 2012 Tuareg rebellion4 in Mali. Since then, West African countries have witnessed a devastating war between government forces and armed Islamist groups, including those affiliated with Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. In Figure 2 we can see the exponential increase of Islamist groups, such as AIQM (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb) or ISGS (Islamic State in the Greater Sahara), in the Liptako- Gourma region from 2014 to 2023.

The goal of these terrorist groups has been to control supply routes and increase their areas of influence through sieges, kidnappings, landmines or improvised explosive devices (IEDs) as tactics of warfare. But the more extreme these groups become and the more the security situation in these countries worsens, the more the military campaigns of the ruling juntas harden. A case in point is Burkina Faso5, which has developed a strategy of total war against jihadists, recruiting and organizing tens of thousands of civilians into self-defense militias.

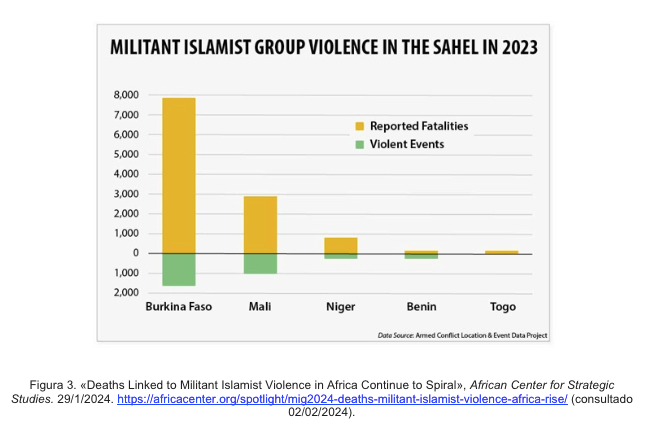

This situation translates into a notable increase in armed conflicts in the area, as we can see in Figure 3, where we can see that Burkina Faso is the country where terrorist activity is most present, especially on the Sahelian side of Al-Qaheda, Jama'at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

This increase in violence and armed conflicts worsens the living conditions of the population, increases tension, alters the political order and hinders economic activity. If we add to this the ineffective response of the elected governments, the consequence is that insecurity and regional violence are the main cause of the sequence of coups d'état and destabilization in the three countries analyzed.

Presence of France and the United States

This instability and growing insecurity in Western Africa has also affected the external actors present in the territory. France and the United States had been, until now, the powers with the greatest presence in the area. Either for political reasons, such as slowing down the expansion of the USSR during the Cold War (1947-1991), or for economic incentives, such as the uranium and oil reserves in Niger.

Since the second half of the 20th century, France has been considered the "gendarme of Africa" and Europe's main representative on the continent. It has maintained close relations with its former African colonies and has carried out dozens of military interventions to maintain its influence in the region, ensure access to strategic markets and natural resources, protect allied regimes and prevent the rise of governments that would go against its interests. A type of relationship that has given the region of African countries with a French presence the name of Franc-Africa6.

The most recent and relevant operations are related to the growing insecurity in the region. Of particular note is Operation Serval7 which began in January 2013 intending to curb the advance of Islamist groups following the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali. In July 2014 it was replaced by Operation Barkhane8. Other European powers also showed interest in intervening through the Takuba Task Force9, integrated into Operation Barkhane.

Nevertheless, in the absence of improvements in the situation, protests by the Malian population increased. This factor, coupled with the two coups d'état in 2020 and 2021, the poor relations of the French government with the new junta and the entry on the scene of the Wagner group, led to the withdrawal of French troops from Mali in 2022.10 This situation was later repeated in Burkina Faso and Niger with their own coups d'état.

These coups have symbolized a revolution for the people of these countries, an opportunity to regain sovereignty and put an end to French influence and privileged access to the political elite and natural resources. At least that is the opinion of some of the African people11, who back their support for the military juntas in the transitional period, arguing that their role is temporary and they will eventually hand over power to a more prepared civilian government.

On the other hand, the United States, which unlike France did not have colonies in Africa, increased its presence in this continent during the Cold War in an attempt to curb the expansion of the USSR's influence. Since then, Washington's main objective in Africa has been to contain jihadism, especially in North Africa and the Sahel because of the growing threat of terrorist groups such as Boko Haram or Al-Qaeda.

In 2007, the US centralized its military actions on the continent through a Unified Combatant Command under the name of AFRICOM. However, after the failure and unfavorable public opinion created by the Iraq war (2003) and the death of US Ambassador Chris Stevens in the Benghazi attack in 2012, the US changed its security policy in the region and reduced its military commitments. Moreover, this international activity was further reduced under the Trump administration.

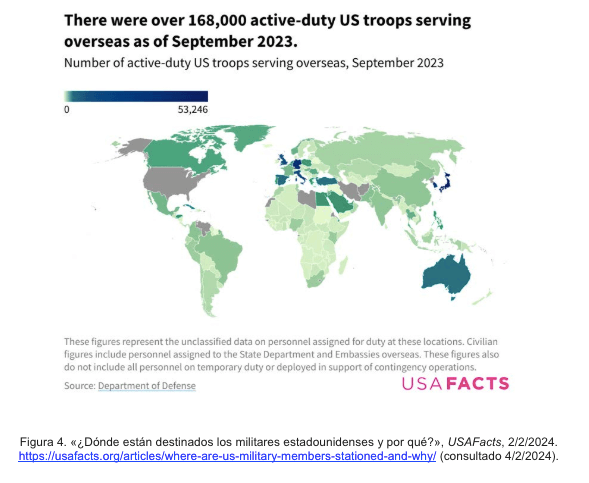

Currently, the US security strategy is focused on the Indo-Pacific, where its main rival, China, is located. In addition, public opinion's refusal to act militarily outside its borders has led the US to intervene only in conflicts where it has very clear and strong interests. Compared to the rest of the world, the U.S. military presence in Africa is negligible.

As can be seen in the map in Figure 4, the external presence of the U.S. serves mainly as support to allied states and as a prevention or deterrence measure against possible threats or conflicts on the planet.

In the face of the coups d'état in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, the US has maintained a firm position defending the reinstatement of constitutional order and its support for ECOWAS, as a fundamental body for the transition processes, and for the countries of the region that maintain and defend democratic principles. Proof of the latter are the diplomatic trips12 of the United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Linda Thomas- Greenfield, to Liberia, Guinea Bissau and Sierra Leone. Where she reaffirmed the US commitment to the fight against corruption, disinformation and the defense of freedom of the press. Yet this was not the only visit of the US government to the African continent. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken has been on a tour of West Africa, highlighting the alarming role of the Russian presence in regional conflicts13 and pledging $45 million to boost coastal security and nearly $150 million in humanitarian aid for Western Africa and the Sahel14.

Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger’s own initiatives

Faced with growing mistrust about the ability of external actors, such as France or the US, to address security problems in West Africa, African states have come together on several occasions to seek their own solution and fight a common problem together.

In 2014, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mali, Mauritania and Niger created an alliance to combat regional insecurity through cooperation and coordination, under the name Sahel G5. However, the alliance was born with several root problems. First, the creation of a force out of pre-existing national armies that carry their own structural and operational challenges. Secondly, its limited funding, as its members are among the poorest and least developed countries in the world15. This is why the alliance lacks the means to achieve its objectives. Finally, the vastness of the territory covered by the region exceeds the capacity of the military force at their disposal.

Moreover, the alliance has not managed to maintain a firm independence from external aid from the West. The G5 Sahel has been supported by the EU with the missions EUCAP Sahel Niger, EUCAP Sahel Mali and EUTM Mali16, and has collaborated with France through Operation Barkhane.

As a result, the G5 Sahel has not worked as expected and in the face of the growing situation of insecurity, instability and distrust of Western powers, Mali was the first country to leave the alliance in 2022 and a year later, in 2023, Burkina Faso and Niger followed17.

Subsequently, on September 16, 2023, the military juntas of these three countries decided to create their own initiative by signing the Liptako-Gourma Charter. The Alliance of Sahel States (AES). A pact by which they commit themselves to intervene, including by the use of force, in favor of the members if one of them is attacked by an external power, in order to re-establish and guarantee the regional and national security of each of them. But the aspirations of this alliance have gone beyond that. In addition to defense, the signatory boards intend to take it into the political and economic realm, as they demonstrated in November 2023 after holding a summit with the ministers of Economy, Industry and Trade18.

These moves on the part of the alliance caused some alarm within ECOWAS, as they further marked the distancing of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger from the economic community. Consequently, a first meeting between an ECOWAS delegation and the Niamey junta was convened for January 10, 2024, but was postponed until January 25, 2024, to negotiate the lifting of sanctions and the transition periods from military juntas to democratic governments. However, of the five members of the ECOWAS commission expected in Niamey, only one showed up19, something which was not well accepted by Niger's military junta and consequently by its allies.

On January 28, 2024, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso announced in a televised appearance and without prior national consultation their exit from ECOWAS, giving as main reasons: the illegitimacy of the sanctions imposed, the betrayal of the founding principles of the alliance, the control of external powers and the failure in the fight against regional insecurity of the alliance. Should this decision materialize, it could have multidimensional consequences.

Although this is not the first time that a member of the alliance has decided to leave (Mauritania did so in 200020), the situation and conditions of ECOWAS then and now are very different. Its cohesion and solidity are not the same as it was in 2000, and the departure of one member is not the same as the departure of three. The consequences in this case could put the regional group in a complicated situation. The end of the free movement of people and goods, the breakdown of the free trade agreement or the return of trade barriers are some of the consequences that would harm economic growth, migratory flows and food security. In addition, ECOWAS would lose its role as a mediator in negotiations on democratic transitions with the military juntas, it would lose about 8% of its GDP21 and the response to terrorism would be even more divided.

However, the process of exiting ECOWAS is long and formal steps have not been taken yet.22 The televised announcement by the military boards of the AES has no legitimacy. They should make a formal notification and, if they do so, they should continue to comply with the obligations of membership until their exit is legally formalized.

This whole process diverts attention away from democratic transitions and redirects public debate, thus benefiting the military juntas who take advantage of it to further develop their new alliance. On February 15, 2024, ministers from the three military juntas met in Ouagadougou to design the institutional and legal architecture of a possible confederation to be formed from the AES to achieve broader integration23.

The AES is a recently created alliance that must gradually develop in form and content, as established in articles 3 and 15 of its founding charter.24 It is a project for the future that needs to be complemented by additional texts and to establish the necessary bodies and mechanisms for its operation in order to expand and extend its frontiers25 in West Africa. Nonetheless, in the current context, this uncertainty and lack of development make it a weak alliance.

In short, the members of the Alliance of Sahel States are in a process of transition and restructuring of alliances in an attempt to distance themselves from Western influence. The very creation of the AES and the informal announcement of their desire to leave ECOWAS have been the first steps, but the next ones do not seem to be clear yet.

In the meantime, the AU has ignored what is happening in this part of the continent. MISAHEL, the mission of this organization in the Sahel has been without a leader since August 202326, and the objectives, purposes and principles27 set out in its Constitutive Act28 seem to have been forgotten.

Thus, in the face of uncertainty, the need for external aid and the disenchantment with Western powers and African organizations, Russia presents itself as an ideal alternative for the Liptako-Gourma countries. A country that offers a new framework of relations where political structures, morals and values are not imposed.

Russia as an alternative for foreign aid to emerging governments

Confrontation with the West is the scenario that the Kremlin anticipates for the next six- year period and this is what the National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation establishes in its 2021 update29. There are several regions in which Russia seeks to reduce the sphere of influence of Western powers, including West Africa.

Since 2010, Russia has included the African continent in its foreign policy. During these years, it has been positioning itself as a possible alternative for African states disillusioned with Western alliances, both politically and militarily, through a hybrid strategy.

On the one hand, Russia has actively participated through the Wagner Group, conducted disinformation campaigns and led an anti-colonial discourse.

As we can see in Figure 5, Wagner is present in Mali and Burkina Faso, among other countries, with active military operations, participating in combat, supporting the military juntas in recent coups and controlling mining resources.

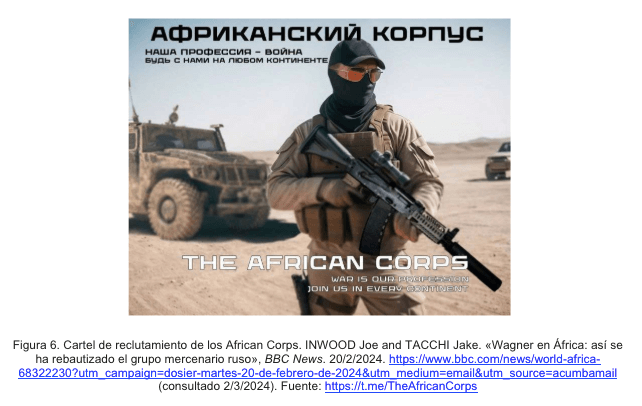

Moreover, following Vladimir Putin's conflicts with the leader of the mercenary group, Yevgeny Prigozhin, and the creation of the AES, this group is being progressively replaced by "Afrikanisky Korpus"30 or "African Corps". A new military corps officially representing Russia on the African continent, taking the security architecture established by Wagner under a more centralized command structure in the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Russia is using the "African Corps" to offer "regime survival packages" to military juntas in exchange for access to natural resources.31 In this way, Russia seeks to expand, obtain mining concessions and establish parallel businesses with which to cover the costs of its operations or even make a profit.32 In addition, with its presence, it manages to dislodge Western companies from an area of strategic importance.

The first major deployment of this new military corps took place in Burkina Faso in January 2024 with 100 Russian military personnel and, since then, it has been gradually taking control of Mali's operations33.

In terms of disinformation campaigns, Russia has relied on the immediacy of social networks to encourage anti-colonialist discourse, revolts against Western-allied governments, and discontent in society. It has also turned to traditional media by expanding the network of the public media outlet Russia Today (RT), through various agreements with African media outlets such as Afrique Media34. These have gone on to disseminate pro-Russian and anti-Western propaganda, emphasizing the decline of the West and presenting Russia as a strong ally that maintains an equal relationship with its partners.

On the other hand, Russia has used diplomatic channels to increase and improve relations with African countries. The summits in Sochi in 2019 and St. Petersburg in 2023 have played a key role in that process, strengthening Russian-African relations through political, economic and cultural cooperation. At the last summit, Russia announced the cancellation of $90 million in debt, the donation of between 25,000 and 50,000 tons of Russian grain and arms contracts with more than 40 countries35. These measures were prompted by Russia's need for international support in the face of the war in Ukraine, which has deteriorated its public image and diplomatic relations.

Russia has increased its relations with the AES countries following the sequence of coups d'état. In November 2023, Kassoum Coulibaly, the Burkinabe defense minister, traveled to Moscow to meet with his counterpart, and in January 2024 the Nigerian prime minister appointed by the military junta, Ali Mahamane Lamine Zeine, did so to discuss a possible expansion of relations with Russia in defense, agriculture and energy36. Moreover, the very creation of the AES took place one day after the defense ministers of Mali and Niger met with the Russian deputy defense minister, Yunus-bek Yevkurov19, demonstrating the close contact between the governments of the two continents.

Threats of Russian presence to the West

This rapprochement of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger with Russia could generate great tensions with the countries of the Western bloc. If they begin to act in favor of Russian interests, Western countries would be threatened, especially the Europeans, but it would also have repercussions for the Americans, thus making the US and the EU unwilling to cooperate with Russia37.

Uranium mining in Niger and illegal immigration are two examples that could become threats to the West.

If Niger grants uranium exploration and exploitation rights to Russia38, this would be perceived by France as a direct attack on French companies already holding such a license39. This would mean increased competition and loss of control of the raw material.

Similarly, if the AES countries allow mass illegal migration through their territory to continue on the way to Europe, this would be a major problem for the Union. Currently, the EU receives in its countries large waves of illegal immigration that exceed its capacity for coordination and response due to the lack of a common migration policy, generating great political and social tensions in several European countries.

Conclusions

The creation of the AES, the possible exit of ECOWAS and the increase in relations between Russia and the emerging governments of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger anticipate a geopolitical reconfiguration in Western Africa.

The increase in terrorist activity, the growing military presence, the neglect by the AU, the loss of power in the region by the U.S. and European countries, the emergence of Russia as a new alternative and the uncertainty of the future of ECOWAS have led West African countries to a process of change.

The attempt by the Liptako-Gourma military juntas to leave ECOWAS is the clearest expression of their countries' weariness with the passivity of the regional organizations and their inability to respond to the growing insecurity in the area. A departure, which, if it were to take place, would have drastic consequences for the region's economy and security. Conversely, if the Liptako-Gourma countries were to remain in ECOWAS, the mere attempt or willingness to leave would have been a clear and strong demonstration of the need for greater involvement in an effective response by the regional grouping and the AU to security problems.

At the same time, the creation of the AES is evidence of the will for independence, change and new solutions in the region. If the alliance is maintained, neighboring countries such as Guinea and Senegal, which also suffer periods of political instability at the moment, could join in the not-too-distant future. However, the AES is currently a weak alliance, with a structure to be built and a rather uncertain future.

The present situation in West Africa is unsustainable and calls for change. Insecurity has become the main factor of regional instability and external aid is still necessary. The AES states, as has already been demonstrated, lack the necessary economic and military capabilities. The question is who will provide this external assistance? Will the US and France maintain their influence in the area or will they be overtaken by Russia?

A complex question since the future of ECOWAS and AES, on the one hand, and the future of foreign aid, on the other, are closely related and directly dependent on each other. The answer poses two scenarios.

In the first scenario, if Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso leave ECOWAS and strengthen the AES bloc, foreign aid is likely to come from Russia. Likewise, if Russia exerts greater influence in the region, the departure of these countries from ECOWAS will be more likely and the future of the AES more stable.

In a second scenario, if Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso remain in ECOWAS and dissolve the AES, the US and EU are likely to remain allies. Likewise, if the Western powers exert greater influence in the area, ECOWAS will be strengthened, preventing the exit of these three countries, and the AES will be weakened, leading to its dissolution.

What does seem to be clear is that Russia and the AES form one bloc and ECOWAS and the Western powers form another. Two incompatible blocs.

Russia defends the military juntas and the Western powers the return to constitutional order. Russia does so through economic and military aid, with the African Corps, and the US, the first Western power, through support and investment in the countries neighboring the AES that maintain constitutional order.

In short, the geopolitical reconfiguration of West Africa is subject to two factors, regional organizations or alliances and foreign aid. These two factors in turn determine the two blocs that will condition the future of the Liptako-Gourma countries. For the time being, it is difficult to predict which bloc will dominate.

Alejandro López Martínez* International Relations and Global Communication Student

at Universidad Pontificia Comillas

References:

1 «Le franc CFA est-il un impôt colonial?», Libération. 24/12/2019. https://www.liberation.fr/checknews/2019/12/24/le- franc-cfa-est-il-un-impot-colonial_1770794/ (consultado 25/11/2023).

2 Esto se debe a que los Estados que utilizan esta moneda deben depositar la mitad de sus reservas de divisas extranjeras en el Tesoro francés y, si desean retirar una cantidad superior a cierto límite en un solo año necesitan la aprobación de Francia.

3 HERRERA, Rémy. «À qui profite le franc CFA?», Afrique XXI. 3/6/2023. https://afriquexxi.info/A-qui-profite-le-franc- CFA (consultado 16/02/2024).

4 GARCÍA MESA, Beatriz. La rebelión tuareg y la sombra de Al Qaeda. Documento de Opinión IEEE 37/2012. https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_opinion/2012/DIEEEO37- 2012_RebelionTuaregSombraAlQaeda_BeatrizMesa.pdf (consultado 27/11/2023).

5 KINLEY, Salmon. «It’s going to get grimmer in the Sahel», The Economist. 13/11/2023. https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2023/11/13/its-going-to-get-grimmer-in-the-sahel# (consultado 28/11/2023).

6 SALDAÑA, Eduardo. «¿Qué es la francáfrica?», El Orden Mundial (EOM). 17/8/2023. https://elordenmundial.com/que-es-francafrica/ (consultado 28/11/2023).

7 SPET, Stéphane. «Operation Serval: Analyzing the French Strategy against Jihadists in Mali», ASPJ Africa & Francophonie - 3rd Quarter 2015. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ_French/journals_E/Volume- 06_Issue-3/spet_e.pdf (consultado 4/1/2024).

8 FUENTE COBO, Ignacio. El Sahel después de la Operación Barkhane. Situación de seguridad y perspectivas de futuro. Documento de Análisis IEEE 23/2022. https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/BoletinesIEEE3/2022/BoletinIEEE26.pdf (consultado 4/1/2024).

9 CHAMORRO, Andrea. «Francia anuncia la finalización de la Task Force Takuba», Descifrando la guerra. 1/7/2022. https://www.descifrandolaguerra.es/francia-anuncia-la-finalizacion-de-la-task-force-takuba/ (consultado 4/1/2024).

10 «Retrait de la force Barkhane du Mali», Élysée, 15/8/2022. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel- macron/2022/08/15/retrait-de-la-force-barkhane-du-mali (consultado 22/11/2023).

11 JONES, Mayeni. «Francia nos toma por idiotas: la tensión contra el país europeo que se vive en Níger tras el golpe militar», BBC News. 29/9/2023. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/cz5emjzgkz1o (consultado 22/12/2023).

12 ADETAYO, Ope. «Blinken looks to bolster West African security partnerships after setbacks», Al-Jazeera, 25/1/2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/1/25/blinken-looks-to-bolster-west-african-security-partnerships- after-setbacks?utm_campaign=dosier-viernes-26-de-enero-de-2024&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail (consultado 27/01/2024).

13 En una entrevista a Jeune Afrique y The African Report A., Blinken afirmó que en los Estados que han apelado al grupo Wagner la violencia, el extremismo y el terrorismo empeoran. Además, aseguró que solo levantarán las sanciones y reestablecerán los programas contra el terrorismo en la región si estos países vuelven al orden constitucional.

14 JEUNE AFRIQUE. «Antony Blinken : “ Avec Wagner, au Burkina Faso et au Mali, la violence et l’extrémisme s’aggravent “». 24/1/2024. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1529798/politique/antony-blinken-avec-wagner-au-burkina- faso-et-au-mali-la-violence-et-lextremisme-saggravent/?utm_campaign=dosier-africa-jueves-25-de-enero-de- 2024&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail (consultado 27/1/2024).

15 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). «UN list of least developed countries». Diciembre 2023. https://unctad.org/topic/least-developed-countries/list (consultado 1/2/2024).

16 «The European Union’s partnership with the G5 Sahel countries», 7/2019. https://www.eucap-sahel.eu/wp- content/uploads/2020/10/factsheet_eu_g5_sahel_july-2019.pdf (consultado 27/12/2023).

17 (DSN) Departamento de Seguridad Nacional. «G5 Sahel: Níger y Burkina Faso anuncian su retirada de la organización regional». 7/12/2023. https://www.dsn.gob.es/es/actualidad/sala-prensa/g5-sahel-níger-burkina-faso- anuncian-su-retirada-organización-regional#:~:text=la%20organización%20regional-

,G5%20Sahel%3A%20Níger%20y%20Burkina%20Faso%20anuncian,retirada%20de%20la%20organización%20regi onal&text=En%20mayo%20de%202022%2C%20Mali,Mali%20como%20presidencia%20del%20grupo (consultado 4/2/2024).

18 «Fractura y reorganización regional: La Alianza de Estados del Sahel», OSINT Sahel. 29/12/23. https://www.osintsahel.com/2023/12/29/fractura-y-reorganizacion-regional-la-alianza-de-estados-del-sahel/ (consultado 4/2/2024).

19 «The ECOWAS delegation cancels its negotiation mission in Niger: persistent tensions and complex mediation», Fatshimetrie. 25/1/2024. https://eng.fatshimetrie.org/2024/01/25/the-ecowas-delegation-cancels-its-negotiation- mission-in-niger-persistent-tensions-and-complex-mediation/ (consultado 27/1/2024).

20 KHALILOU Diagana. «Malgré son retrait, la Mauritanie reste proche de la Cédéao», Deutsche Welle. 31/1/2024. https://www.dw.com/fr/retrait-mauritanie-cédéao-burkina-mali-niger/a-68129115 (consultado 28/2/2024).

21 EXPANSIÓN. «Economía y datos de la CEDEAO». https://datosmacro.expansion.com/paises/grupos/comunidad-

economica-estados-africa-occidental (consultado 10 /2/2024).

22 De acuerdo con el artículo 91.1 del tratado que rige la CEDEAO: «Todo Estado miembro que desee retirarse de la Comunidad deberá notificarlo por escrito con un año de antelación al secretario ejecutivo, que informará de ello a los Estados miembros. A la expiración de este plazo, si no retira dicha notificación, dicho Estado dejará de ser miembro de la Comunidad». Y en conformidad con el artículo 91.2.: «Durante el período de un año mencionado en el

art. 91.1, dicho Estado miembro seguirá cumpliendo las disposiciones del presente Tratado y seguirá obligado a cumplir las obligaciones que le incumban en virtud de este».

Revised Treaty of the Economic Community of West African Countries (ECOWAS), ECOWAS Commission. 24/7/1993. https://ecowas.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Revised-treaty-1.pdf (consultado 1/2/2024).

23 «Burkina, Mali, Niger: les ministres de l'AES réunis à Ouagadougou en vue de créer une confédération», Radio France internationale. 15/2/2024. https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20240215-burkina-mali-niger-les-ministres-en-l-aes- réunis-à-ouagadougou-en-vue-de-créer-une-confédération (consultado 16/2/2024).

24 «Charte du Liptako-Gourma instituant l'Alliance des États du Sahel entre le Burkina Faso, la République du Mali, la République du Niger», Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, de la Coopération Regionale et des Burkinabè de l’Extérieur. 18/9/2023. https://www.mae.gov.bf/detail?tx_news_pi1%5Baction%5D=detail&tx_news_pi1%5Bcontroller%5D=News&tx_news_ pi1%5Bnews%5D=897&cHash=8d3d29ada5cf8deec05c453414017c17 (consultado 20/2/2024).

25 De acuerdo con el art. 11 de la Carta de Liptako-Gourma, la Alianza está abierta a cualquier otro Estado que comparta las mismas realidades geográficas, políticas, socioculturales y que acepte los objetivos de la AES.

26 «Eight Priorities for the African Union in 2024», International Crisis Group. 14/2/2024. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/african-union-regional-bodies/b195-eight-priorities-african-union- 2024?utm_campaign=dosier-viernes-16-de-febrero-de-2023&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail (consultado 15/2/2024).

27 Entre dichos objetivos, propósitos y principios resaltan: promover la unidad y la solidaridad de los Estados africanos, coordinar e intensificar su cooperación y esfuerzos para lograr una vida mejor para los pueblos de África, promover la cooperación internacional, establecer una política de defensa común para el continente africano, o el respeto de los principios democráticos, los derechos humanos, el Estado de derecho y la buena gobernanza.

28 Constitutive Act of the African Union, 11/7/2000. https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/34873-file- constitutiveact_en.pdf (consultado 10/2/2024).

29 LABORIE, Mario. «La Estrategia de Seguridad Nacional de la Federación Rusa (julio 2021): un manifiesto hacia la confrontación con Occidente», Global Strategy. 9/9/2021. https://global-strategy.org/la-estrategia-de-seguridad- nacional-de-la-federacion-rusa-julio-2021-un-manifiesto-hacia-la-confrontacion-con-occidente/#_edn1 (consultado 18/12/2023).

30 «Las relaciones de Burkina Faso y Rusia entran en una nueva etapa», OSINT Sahel. 26/1/2024. https://www.osintsahel.com/2024/01/26/las-relaciones-de-burkina-faso-y-rusia-entran-en-una-nueva-etapa/ (consultado 28/1/2024).

31 INWOOD Joe and TACCHI Jake. «Wagner in Africa: How the Russian mercenary group has rebranded», BBC News. 20/2/2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-68322230?utm_campaign=dosier-martes-20-de-febrero- de-2024&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail (consultado 2/3/2024).

32 De acuerdo con el «Blood Gold Report» (https://bloodgoldreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/The-Blood- Gold-Report-2023-December.pdf) en los dos últimos años, Rusia ha extraído oro de África por valor de 2.500 millones de dólares que probablemente han contribuido a financiar su guerra en Ucrania.

33 LÓPEZ MIRALLES, Iván. «Rusia avanza en África: Las African Corps desembarcan en Burkina Faso», The Political Room. 16/2/2024. https://thepoliticalroom.com/blog/rusia-avanza-en-africa-las-african-corps-desembarcan- en-burkina-faso?utm_campaign=dosier-viernes-16-de-febrero-de- 2023&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail (consultado 17/2/2024).

34 «African and Russian Media Unite!», Afrique Media. 15/2/2023. https://afriquemedia.tv/2023/02/15/african-and- russian-media-unite/ (consultado 17/12/2023).

35 MUÑOZ PANDIELLA, Lluís. «Rusia trata de seducir a África: Putin asegura que estudia plan de paz sobre Ucrania», France 24. 28/7/2023. https://www.france24.com/es/europa/20230728-rusia-trata-de-seducir-a-áfrica-putin- asegura-que-estudia-plan-de-paz-sobre-ucrania (consultado 20/12/2023).

36 FAULCONBRIDGE, Guy. «Niger's junta-appointed PM in Russia for talks», Reuters. 16/1/2024. https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/nigers-junta-appointed-pm-in-russia-for-talks?utm_campaign=dosier-africa- miercoles-17-de-enero-de-2024&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail (consultado 20/1/2024).

37 Josep Borrell, vicepresidente de la Comisión Europea y alto representante de la Unión para Asuntos Exteriores y Política de Seguridad ha asegurado que la UE no colaborará con el nuevo cuerpo militar ruso, «African Corps».

Aunque la UE todavía tiene una misión de entrenamiento conocida como EUTM (European Union Training Mission) Mali y una misión civil de gestión de crisis, EUCAP Sahel (European Union Capacity Building Mission) en Mali y Níger, estas podrían llegar a su fin si el acercamiento de estos países a Rusia continúa.

[«EU's Top Diplomat Says Russian Influence Causing Dilemma in Sahel», Reuters. 31/1/2024. https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2024-01-31/eus-top-diplomat-says-russian-influence-causing-dilemma- in-sahel?utm_campaign=dosier-viernes-2-de-febrero-de-2024&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acumbamail (consultado 4/2/2024)].

38 En documentos del Gobierno ruso se han visto plasmadas proposiciones para presionar a Níger y que este corte a Francia los suministros de uranio29. Elemento químico del que el sector energético francés tiene gran dependencia. 39 PÉREZ, Rafael. «Francia responderá "de inmediato y con decisión" en caso de ataque contra sus intereses en Níger», France 24. 30/0/2023. https://www.france24.com/es/áfrica/20230730-francia-responderá-de-inmediato-y-con- decisión-en-caso-de-ataque-contra-sus-intereses-en-níger (consultado 10/2/2024).