The spirit of coexistence

It has been published by Mexican writer Ricardo Cayuela in his young publishing house Ladera Norte. The reader will find in this work a selection of articles published in the newspaper between 2018 and 2024 in which he addresses current issues of great concern such as Sánchez's ambition for power, independence in Catalonia, nationalism, the institutional crisis, the fragility of democracy, the press... Also a more international perspective: the war in Ukraine or the political situation in the United States and Latin America.

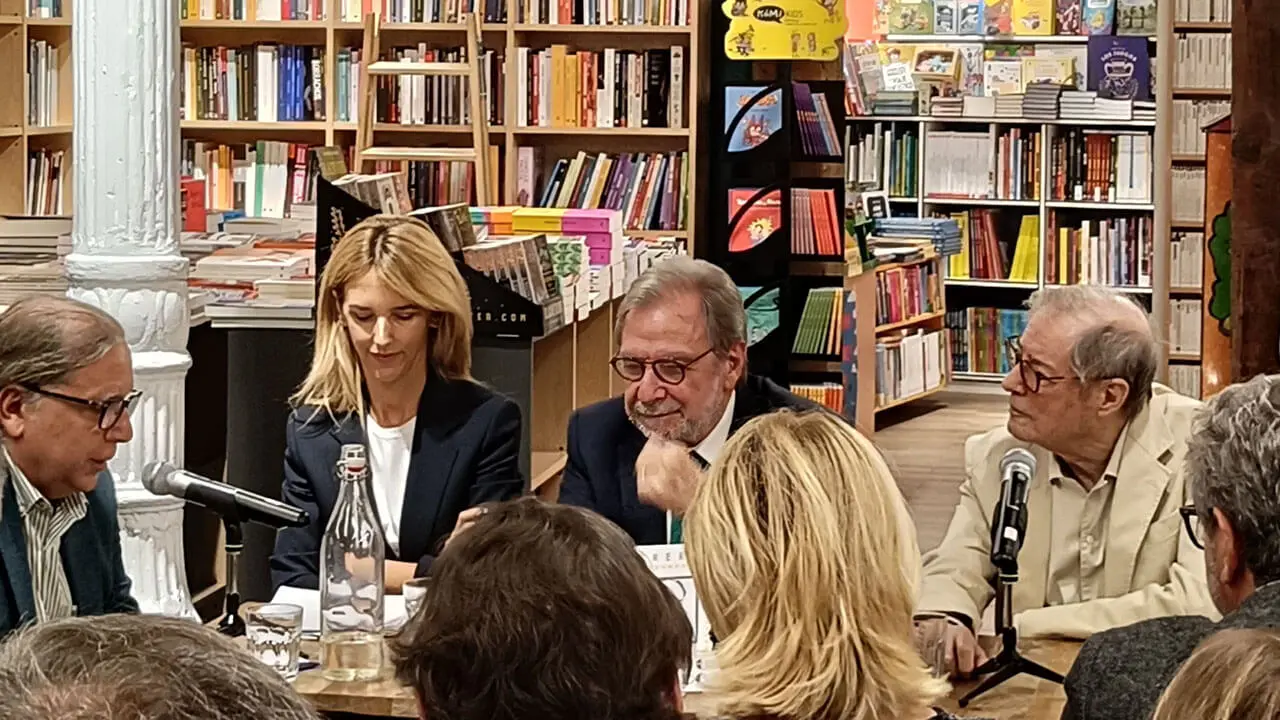

This week, the Antonio Machado bookshop in Madrid hosted the presentation of ‘El efecto Sánchez’. Cayetana Álvarez de Toledo, a PP MP, and the academic Félix de Azúa, as you know, one of the founding intellectuals of Ciudadanos, sat next to Juan Luis Cebrián to talk about the book, also about politics and the rejection of President Pedro Sánchez's desire for power.

I admit that, on seeing the invitation, I thought how much everything was changing for none other than Cebrián, whom no one would label a right-wing man, to choose these table companions for something as important as presenting his work. Curious, because Álvarez de Toledo herself also wondered what Jesús Polanco, the former president of Grupo Prisa and the person to whom the author dedicates his book, would think when he saw her sitting there. She herself replied: ‘That Cebrián has gone mad’.

If all those who ‘have gone mad’, and I am using the word madness, for the same reasons as Cebrián, that is, for wanting freedom of expression and of the press, a united country, that those who commit crimes comply with the law, equality between communities, the right to inform, a real division of powers, a fair justice system and a long etcetera, were in the old so-called madhouses, we would need many millions to build new places to put them.

In 2017, Cebrián retired, and, as he himself acknowledged, he stopped having those cautions that are essential depending on where and how you are, and began to enjoy a freedom ‘like never before’. His articles, many of them collected in this book, confirm this. Sánchez's lust for power at any cost, his lack of transparency, his desire to control the press... ‘his betrayal of the spirit of the Transition’ resounded at this event, where it was also recalled that the world ‘is governed by idiots, both on the right and on the left’. Idiots... very dangerous, I would add. It is enough to open one's eyes and take a tour of the different countries. But Cebrián's great freedom has also had its consequences, because the founder of an essential newspaper at a key moment in Spain's history was dismissed by the current board of directors last April as Honorary President.

These are direct and forceful words from Cebrián that we have already heard from other socialists of yesteryear, each in their own way, such as Felipe González, Alfonso Guerra, Joaquín Leguina..., those who truly knew what it was to conquer democracy after more than forty years of dictatorship, those who lived through exile and persecution, those who bet on the future, on a just society, those who knew that only by overcoming resentment, hatred and vengeance could a better tomorrow be built.

Hopefully, and soon, the optimism of one of the most important journalists of the Transition will come true and the wish said aloud in the crowded Antonio Machado bookshop will be fulfilled: ‘We must recover the spirit of coexistence’.