Closed elections: Turkey on tenterhooks

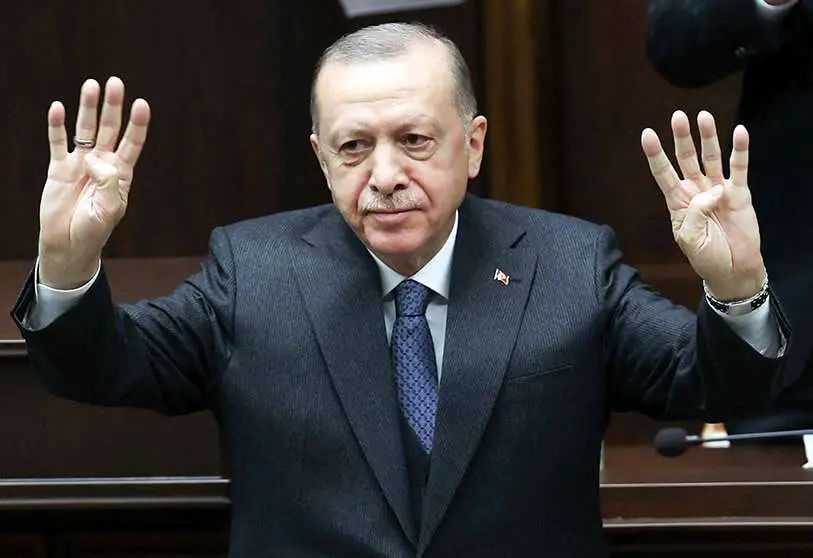

Erdogan has not won the elections in Turkey. If all goes according to plan (at the time of writing this column) there will be a run-off election on 28 May.

The sentimental impact of the unfortunate earthquake of 6 February combined with the weariness of a certain part of the population that wants change in the face of rising inflation and deteriorating purchasing power has taken its toll on this old political wolf: since March 2003, Erdogan has been in power, he did so as prime minister until August 2014 and then won the presidency and has stayed on, election after election.

This time there is a chance, however slim it may seem, that the 69-year-old politician will go home; and not just because his main opponent, Republican Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, is leading a broad coalition of parties against him. It is because a significant part of the Turkish population has been awakened to an ultra-nationalist sentiment.

Five per cent of the votes cast at Sunday's polls favour the ultra-nationalist Sinan Oğan. The definition of who will govern the Turkish people will not be so simple, starting with the composition of the parliament.

Expectations of a close race marked a parliamentary and presidential election vote that has also become a kind of referendum on Erdogan's twenty years in power.

Two decades in which the Turkish nation has undergone constant transformations starting with its own age groups: Turkey has the largest youth population in Europe, most of them were born in the Erdogan era, they have never known another president and many have been able to vote for the first time.

Quite remarkable have been the long queues of voters. When people go out to vote it is because they want change, the question is whether their still president will be able to recognise the victory of his main opponent in the second round.

There is a lot of concern among the Turkish population: some fear that without Erdogan, the rise to power of opposition groups will open the door to a strong political purge with a certain air of revenge. Among the political groups supporting the Republican Kılıçdaroğlu is the party of the Kurdish minority, which during Erdogan's twenty years in power has suffered all kinds of internal and external persecution.

Not only is the new role of minorities at stake, but there are also fears of ethnic-religious conflicts. A few hours before the elections, Erdogan held a mass prayer in the ancient Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia that he himself converted into a mosque three years ago because he wields an all-encompassing Islamist power that he has imposed throughout the country.

A COLLATION

It is not only the future of Turks in Europe as a whole that is the focus of attention in these elections because Turkey's international role in the Erdogan era has not been insignificant - quite the contrary.

Erdogan presumes to get along well with protagonists and antagonists. In the Russian invasion of Ukraine he has been a reasonable mediator; for a start he managed to unblock Ukrainian grain and cereal exports from Russian-controlled ports.

However, the export licence expires every 120 days and will have to be renewed on 18 May under Russian threat of non-renewal. What role will opposition leader Kılıçdaroğlu play in this regard is a matter of concern.

Turkey, Ukraine, Russia and the UN inspect all incoming and outgoing ships. If Turkey withdraws from the agreement it will end up as a dead letter. Kılıçdaroğlu, if he governs, will represent six political parties among which it will be necessary to negotiate and agree, for example, on his role in the invasion of Ukraine and his relationship with Vladimir Putin's Russia. A 360-degree turnaround is also to be expected in the Syrian civil war, which it is partly fuelling with its interventions and arms supplies to rebel groups opposed to Bashar al-Assad's regime.

Turkey's position to accept Finland into NATO, a decision that has been delayed for almost a year since its proposal at the NATO summit in Madrid, has not prospered in the case of Sweden because Erdogan's position has been very clear on the matter, pointing to the Swedish government as responsible for harbouring Kurdish terrorists. If he loses power, perhaps a window of opportunity could open for Swedish membership in the Alliance.

What is most feared in Europe is that at the end of the day, Erdogan's co-religionists and cronies, if he loses the second round, will not accept him and the country will end up in a chaos of instability and ungovernability. The EU, above all, needs Turkey to continue to honour its commitments (for which it receives funding) to keep illegal immigrants trying to reach various parts of the EU on its territory.

For the time being, all is uncertainty and uncertainty until the second round of elections.