Nord Stream, the fate of Europe

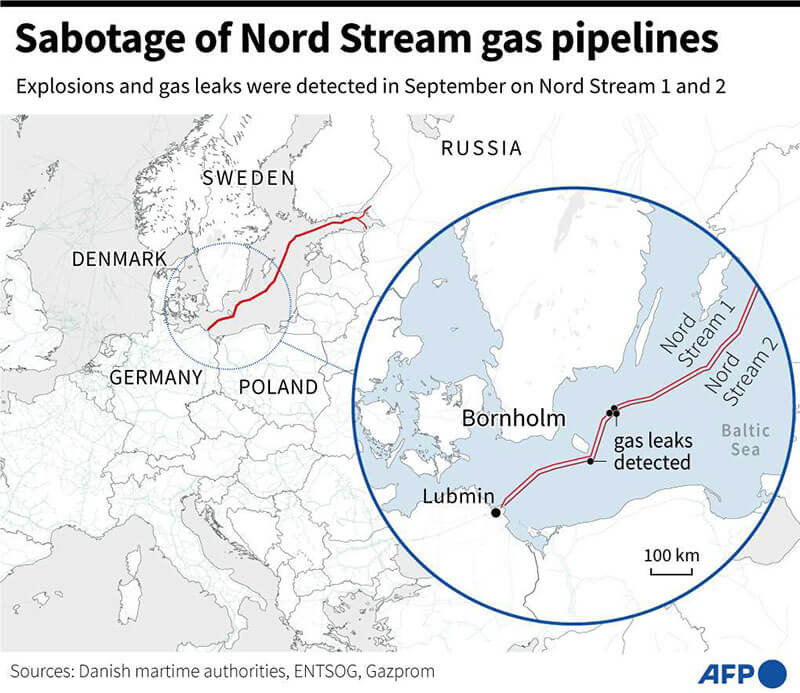

The September 2022 sabotage of the Nord Stream underwater pipelines, designed to transport Russian gas to Europe from Germany, had become one of the central mysteries of the war in Ukraine, giving rise to numerous accusations and conjecture.

The Polish Prosecutor's Office stated that it had received the arrest warrant, issued by Germany, in June for a suspect who was living in Poland at the time. The suspect, in accordance with German privacy laws, left the country before Polish authorities could arrest him, according to a spokesman for the prosecutor's office in Warsaw.

The construction of Nord Stream is one of the most important geopolitical events of the post-Cold War era, as the EU's economy was heavily dependent on Russian gas imports.

Although the Green Pact envisages a carbon neutral Europe by 2050, natural gas remains a key part of the energy matrix, as coal was being phased out and renewable energy was not yet ready to fully absorb that of traditional sources.

EU domestic gas production was declining rapidly and there was not enough gas at affordable prices from alternative suppliers to replace Russian production. The Nord Stream 2 pipeline, launched in 2015, connects Russia and Germany directly across the Baltic Sea, following a similar route to Nord Stream 1, in service since 2011. Construction was delayed for several years, due to legal disputes and, since 2019, also US sanctions. However, pipe-laying continued and was scheduled to be completed in a few months.

Few energy projects have been as hotly debated as Nord Stream 2. The pipeline's owner, Gazprom, a Russian state-controlled company, argued that it was needed to meet the EU's growing demand for gas imports. The German energy sector also considered, and considers, that the pipeline is a viable commercial project. Some opponents point to the environmental impact of the pipeline's construction, as well as the contradiction between the EU's climate objectives and long-term investments in infrastructure for fossil fuel imports. Another contentious issue was why underwater pipelines and not through the Baltic States.

However, the geopolitical implications of the pipeline are its most controversial aspect. Critics, including several EU member states, describe Nord Stream 2 as a Kremlin project to create European geopolitical servitude to Russia. If linked to the TurkStream pipeline that brings Russian gas to south-eastern Europe, it will ultimately allow Russia to deprive Ukraine's ailing economy of much-needed transit fee revenues. The pipeline would be a tool designed to perpetuate Russia's dominance over EU energy markets and compromise Europe's strategic autonomy.

Despite these concerns and objections from the Obama, Trump and Biden Administrations, the German government, under the leadership of former Chancellor Angela Merkel, went ahead with construction of the Nord Stream 2 project. The Biden Administration lifted sanctions against German entities involved in Nord Stream 2 after an agreement with Berlin that it would allow gas to return to Ukraine and take steps to shut down the pipeline if Russia attempted to use it to force political concessions. Gazpron's CEO, it should be noted, was former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder.

Now that Moscow is waging all-out war in Ukraine, Germany has had to reconsider its ties with Russia, which, despite years of warnings from the US and its Eastern European allies, have left Germany deeply dependent on Russian gas. That dependence grew out of a German belief, espoused by a long saga of chancellors, industry leaders, journalists and the public, that a trade-linked Russia would have too much to risk in a conflict with Europe, which would make Germany more secure and at the same time benefit its economy. Proof of this is the shrinking budget for the Bundeswehr.

More than 16 years ago, when the Nord Stream pipeline was little more than an idea, a Swedish government study warned of the risks inherent in installing a geopolitically critical piece of energy infrastructure along the bed of the Baltic Sea. According to analysts, the pipeline would be vulnerable to even the most rudimentary form of sabotage, while underwater surveillance would be unreliable. Already in 2007, a study by the Swedish Defence Research Agency envisaged a scenario where: ‘A single diver would be enough to plant an explosive device’.

Today, European researchers face an almost identical scenario. The Swedish authorities, who are conducting a criminal investigation, have concluded that a state agent was most likely responsible for the September explosion that ruptured the gas pipes. Officials and experts say the explosives, as the Swedish report warned, were placed on the seabed by submarines or divers.

Germany is deeply affected by the war in Ukraine, its government is aware that Europe is facing growing geopolitical and security challenges, not only because of Russia's full-scale war, but also because of other conflicts in the Middle East, Central Africa and North Africa. This war is seen as the end of Europe's post-Cold War security order and represents the greatest threat to European security since the end of World War II. The paralysis of Nord Stream is symbolic.

The fundamental change in relations with Russia has necessitated a rethink of this relationship and of the role Germany wants to play in European and transatlantic relations. The German business model, based on cheap Russian pipeline gas, is a thing of the past. Apart from the demand for greater deterrence, there is no talk of a new German or EU strategy towards Russia, no long-term prospects for relations with Russia and no other strategic approach. The current German government is in crisis management mode, without a vision of its own role in Europe and the world in the new geopolitical and security environment. If this continues, Germany could further lose its role as Russia's chief negotiator and Europe's main crisis manager, a role it has played for the past decades.

This war is a stress test for German policy, which needs a more comprehensive and visionary approach to European security and the European project. Germany's increasing focus on the Global South, as we have seen in the last two MSCs, is not backed by a strategic approach or sufficient resources; as a result, it appears rather instrumental. In the post-Soviet region, we observe the end of Russian hegemony, driven by the enormous amount of resources the country is spending on its brutal war in Ukraine, Western sanctions and the growing interest of countries in Central Asia, the South Caucasus and Eastern Europe in countering Russia's influence.

As Spaniards, we are directly affected by this situation. Spain endures a double danger, the one that affects it due to its geopolitical situation and the one self-inflicted by internal issues, whose infantile component makes us a pariah in the international context. The post-World War II multilateral order guaranteed by the United States is coming to an end and the institutions traditionally supported by Spain, such as the UN, the OSCE and the Council of Europe, are becoming dysfunctional.