50th Anniversary of the Spanish Cultural Institute in Dublin

- Spanish Cultural Institute in Baghdad

- Spanish Cultural Institute in Dublin

- Creation of the Instituto Cervantes

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the creation of the Spanish Cultural Institute in Dublin (ICD). Neither the Spanish Embassy in Ireland, nor the Instituto Cervantes (IC), which absorbed the centre, have seen fit to celebrate this anniversary. I - who knew and appreciated the meritorious work of this institution - would like to take the liberty of making a spear in its memory. Spain is a medium-sized power in the political or economic sphere, but it is a great power in the cultural sphere, which is why I have always believed that Spanish diplomacy should focus especially on this highly profitable field, but the various Spanish governments have not shared this criterion and have undervalued this wonderful asset, to the point that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, when for economic and financial reasons it had to reduce its staff, the first Directorate-General to disappear was the Directorate-General for Cultural Relations.

Spain has neglected the external projection of its extraordinary culture, and the Ministry of Culture has been considered a "Maria" in which to place some flower minister, has shared functions with Education and Sport, and on many occasions has been relegated to the level of Secretary of State. Its budget allocation has always been minimal. Despite the fact that the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations considers the development of cultural and scientific relations between states to be one of the basic functions of embassies, Spanish governments do not provide them with sufficient means to carry out this essential task, even though they are entrusted with this function. Hence, the exercise of cultural action abroad depends on the capacity of the Heads of Mission and their ingenuity in obtaining resources to carry out this action when they are lacking. The establishment of cultural centres abroad was often the result of the initiative of ambassadors, cultural attachés or professors, as in the cases of the Cultural Institutes in Baghdad and Dublin.

Spanish Cultural Institute in Baghdad

When I arrived in Iraq as ambassador in 1983, I found a small Spanish Institute (ICB) run by a former scholarship holder, Juan Casado, who - together with his wife Mercedes - gave Spanish classes to the Iraqis. The Ministry paid the rent for the modest premises in which the Institute was located and the salaries of the teachers. The rest of the staff - a third teacher, a secretary-interpreter and a caretaker - were paid from student fees. The Embassy did not have any budget for cultural expenses, but - in accordance with my convictions - I devoted a large part of my activity to promoting cultural action, for which I had the collaboration of the ICB.

I enhanced the "status" of the director by appointing him Honorary Cultural Attaché and encouraged cultural action. I established cordial relations with the Director General of Musical Arts, the Chaldean Christian Munir Bashir - a renowned Arabic oud player of international fame - who offered us free premises for events organised by the Embassy and supported us in overcoming the many bureaucratic and administrative formalities. Thanks to his generous help, we were able to organise annual Spanish-Iraqi Cultural Weeks. Moreover, I managed to convince the Directorate General for Cultural Relations and the Spanish-Arab Institute of Culture (IHAC) to include Iraq in the itinerary of artists funded by the Ministry. At first they were reluctant because of their fear of performing in a country at war, but - as they saw that the Embassy's cultural activities were increasing and the situation in Baghdad was relatively calm - they cooperated fully.

During the 1st Week, an exhibition-competition of Iraqi painters in homage to Picasso and Miró was held, in which 104 works were presented, and the winners were paid a trip to Madrid - courtesy of "Iraqi Airways" - to take part in the final of the competition organised by the IHAC in all the Arab countries. A cycle of films by José Luis García Gómez was presented, lute concerts were given by Bashir himself, piano concerts by the Iraqi-Armenian Beatriz Ohanesian, and guitar concerts by Pablo de la Cruz. In the 2nd, an exhibition of "Spanish engravings of the 18th and 19th centuries" was held, films by Luis García Berlanga were shown, Ohanesian gave a concert of Spanish music and the flamenco group "Manolete y la Tolea" performed. In the 3rd, an exhibition of photographs on "Arab Art in Spain" and a series of films by José Luis Garci were presented, the ballet "Estampas de España" by Carmela Greco performed, and there were concerts by the Iraqi Percussion Group, the Bayarek Music Company and the Sumer Chamber Orchestra, which gave a concert of Spanish music. During the four years I was in Iraq, the guitarists Vicente Monje "Serranito", Miguel Ángel Jiménez Arnaiz, Ignacio Flores, Manuel Cortés and Pablo García, the pianists Antonio Baciero and Enrique Pérez de Guzmán, the Spanish Dance Group of Carmen Cubillo and the Company "El Rapsoda" of Enrique Paredes performed there. A magnificent conference was also given by the writer Antonio Gala.

The ICB came to occupy a central position in Iraqi cultural life, on a par with the French Cultural Centre and the British Council, and all without costing the Embassy a single dinar. The most original action was the organisation of an exhibition of "Engravings of Spanish cities", whose funds came from the reproduction of engravings in the Chancellery, the Military Attaché's Office, the ICB and the homes of the members of the Embassy. Although they were copies of old engravings, they were very good and the exhibition was favourably received by local critics. I also invited to the residence a friend from Seville, the soprano Fuencisla Martín, and her accompanist, the pianist Marisa Arderius, who gave a recital of Spanish songs, without us having to pay the "cachet", or the tickets, which were given to them by "Iraqi Airways". With a little imagination, an important cultural action could be carried out at no cost to the public purse.

Spanish Cultural Institute in Dublin

When I changed posts, I found that the situation at the Embassy in Ireland was not very different from that in Iraq, except that the Spanish Cultural Institute in Dublin (ICD) was much more developed than the one in Baghdad, as it had a well-established system for teaching Spanish and also carried out some cultural activities. In the absence of a budget, I had to continue resorting to the "sablazo ilustrado" system, so that the Mission and the Institute could develop a cultural action worthy of the name.

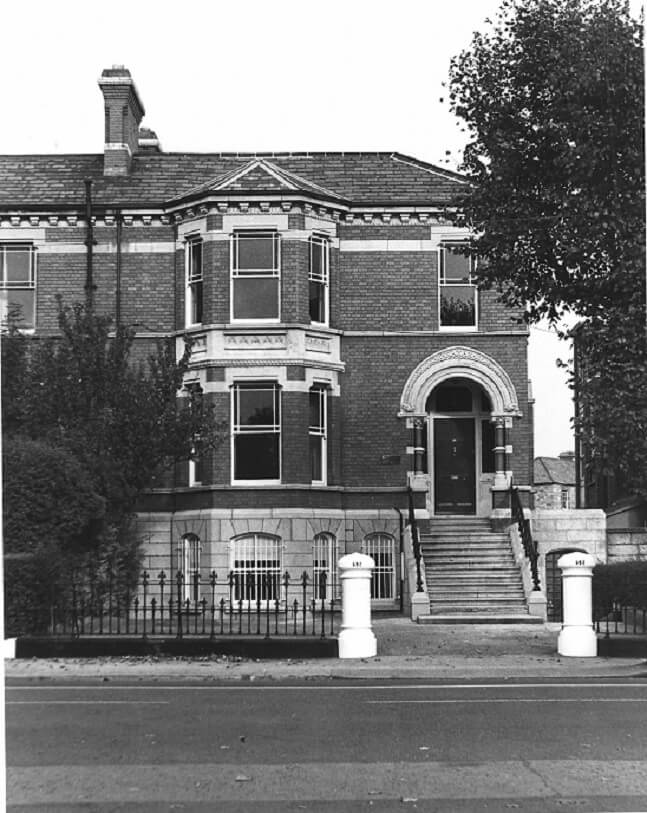

The ICD was officially created in 1975 on the initiative of the then Reader in Spanish at Trinity College (TCD), Antonio Sierra, with the support of Ambassador Joaquín Juste. That year, the Irish Minister for Education, Richard Burke, and the Director General for Cultural Relations, José Luis Messía, inaugurated the Institute in a villa in a residential neighbourhood of Dublin near the Embassy. The Ministry paid the rent for the premises and the salaries of the director, the librarian and a secretary. The salaries of the other staff - between 5 and 7 teachers, an English secretary, a caretaker and a cleaner -, management costs and cultural activity were financed by income from student fees, which were paid into a Special Revenue Account, controlled by the Embassy and the Ministry.

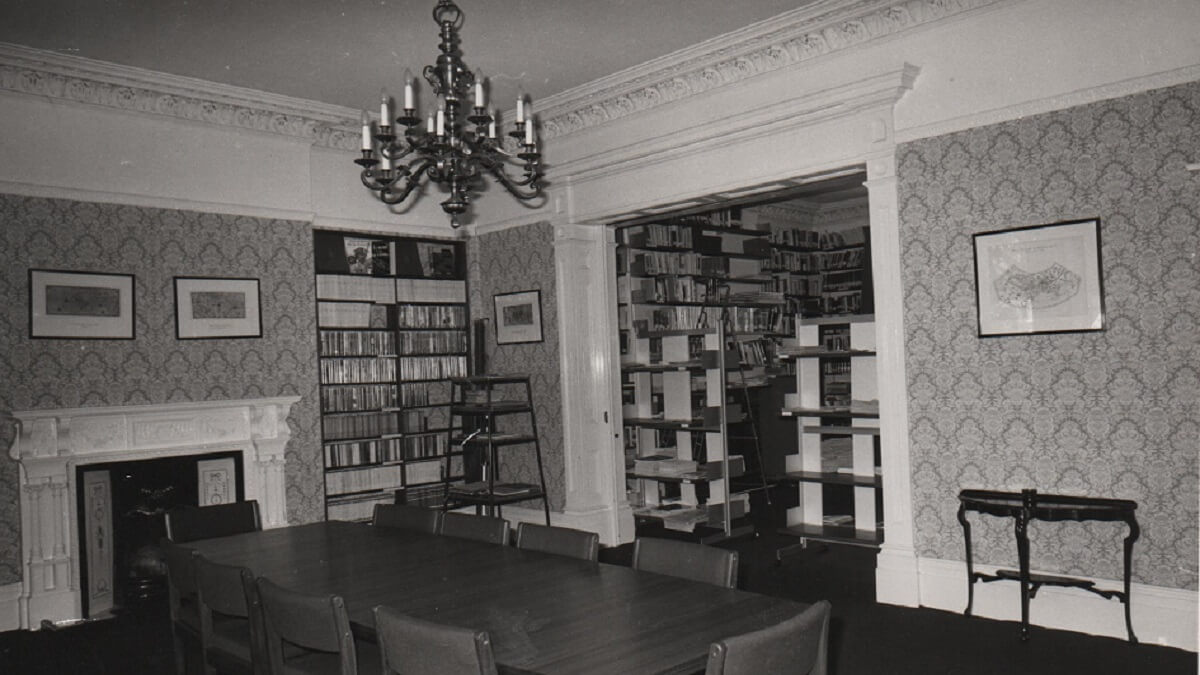

The number of students gradually increased from 379 in 1987 to 950 in 1990. The ICD offered a comprehensive Cultural Information Service and a more modest Commercial and Tourist Information Service, and published a monthly bulletin, "Spanish Cultural Institute News", which outlined its activities and reported on issues of interest to teachers and students of Spanish, and to the Hispanic community in Ireland. It created a Resource Centre and an International Spanish Dissemination Service, which provided the universities with Spanish Departments - TCD, University College Dublin, Galway and Cork, Dublin City University, and the National Institute of Higher Education (NIHE) in Limerick - and hundreds of schools and colleges with newspapers, magazines, books, films, records and cassettes. Catalan, Galician and Basque classes were also offered, provided that a minimum of 10 students could be reached, which was never achieved. The few who showed interest were given the guidance of native teachers versed in these languages.

Students who passed the required tests were given a Certificate of Spanish, which was eventually recognised by the Ministry of Education. An annual prize was awarded to the best Spanish student in all Irish schools and exchanges between Irish and Spanish teachers and students were facilitated. The dissemination of Spanish reached the furthest corners of the island thanks to the work of the ICD.

The cultural activity of the ICD was framed within the framework of the Spanish-Irish Cultural Cooperation Agreement of 1980. The Institute regularly held conferences, film screenings and concerts in its facilities. The video "España día" and one of the films sent by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were shown fortnightly and the First Week of Spanish Cinema in Ireland was organised. Every year it organised a guitar concert in homage to Andrés Segovia at the Museum of Contemporary Art and sponsored a series on the "History of the Spanish guitar", in which native guitarists such as Alan Grundy, Simon Taylor and Luke Tobin participated and collaborated in the concerts of Andrés Segovia, Serranito, Vicente Amigo and Paco Peña.

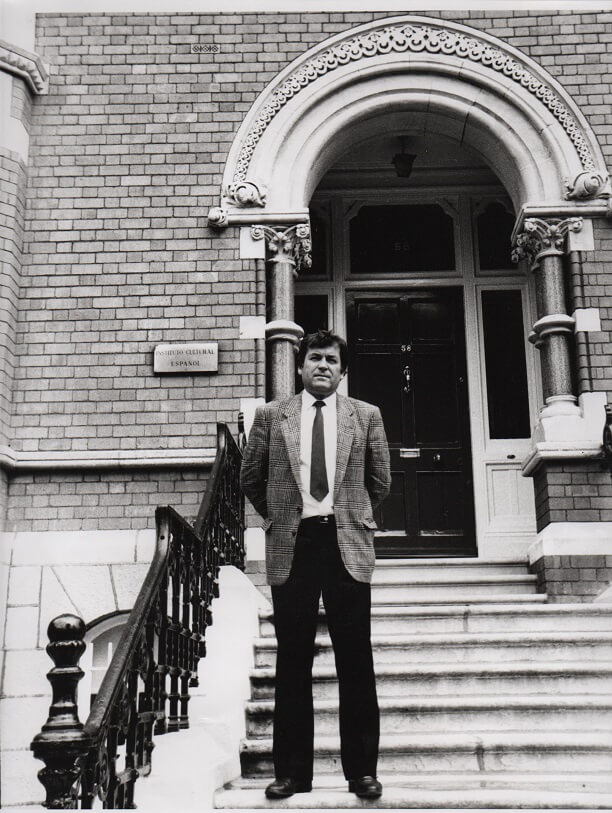

The first thing I did when I arrived in Dublin at the end of 1987 was to appoint the director of the ICD as honorary cultural attaché, I integrated him into the management team of the Embassy and I took an active interest in the educational and cultural activities of the Institute. I took advantage of the good contacts I had with the leadership of the Directorate General for Cultural Relations to ask them to include Ireland in the "tournées" of artists sponsored by them, to which they agreed.

I focused on the organisation of cultural activities, especially on the occasion of the celebration in 1988 of the 400th anniversary of the Great Armada, whose presence had had wide repercussions in Ireland due to the sinking of 26 of its ships off its coasts. With the collaboration of the Institute of Naval History and Culture and the Naval Museum of Madrid, the Simancas Archive, the National Museum of Ireland and Maynooth College, we organised a magnificent exhibition on "The Spanish Navy at the end of the 16th century and Spanish-Irish relations", which was shown at the Civic Museum in Dublin, University College Galway, the Stredagh Armada Museum and the NIHE in Limerick. I attended with the President of the Republic, Patrick Hillery, the unveiling of a memorial in Stredagh in honour of the shipwrecked Great Armada and we sponsored the "Cuellar Trail", a Navy captain who survived the wreck of the frigate "Latvia".

The Embassy organised in Sligo, together with UCD, an international seminar on "The Great Armada, Spain and Europe", during which Seoirse Bodely's cantata "Irish Letter", inspired by the missive in which Francisco de Cuéllar described his spectacular adventures in Ireland, was performed for the first time. I also participated in the Galway Cemetery in the tribute of the "Old Ocean Sea Tertiary" to the 300 crew members of two of the Navy ships ordered murdered by the English Governor of Dublin Sir William Fitzwilliam, and in the unveiling of other memorials in Kinagoe Bay and Dun Chaoin. I attended the Ennis Arts Festival dedicated to the Grand Armada, where Michael O'Suilleabhain's cantata "Nights in Clare Gardens" was premiered, and the Kilkenny Festival, where Victoria de Los Angeles gave a recital of Spanish songs and the chamber group "Hesperion-XX" gave a concert on 16th century Spanish music. I participated with Cardinal O'Fiaich in a meeting of the Donegal Academy of History also dedicated to the Armada and co-chaired with the President of An-Post the launch of a commemorative stamp reproducing the ship "Duquesa de Santa Ana". The ICD organised a literary competition on the Amada among Irish school children.

The highlight of the celebrations was the stay for a few days in the port of Dublin of the school ship "Juan Sebastián Elcano", on board of which a round table on "The Great Armada" was held, a concert on early Spanish music performed by the Chamber Group "Taller Ziryab", and a multitudinous reception attended by "all" Dublin. An unusual procession of the image of the Virgin of the Rosary, "La Galeona", escorted by the Spanish midshipmen to the port chapel, where a solemn "Te Deum" was held along the quays of the River Liffey. It was an excellent calling card for the History and Culture of Spain, hitherto ignored in Ireland because of English propaganda.

From the moment I presented my credentials, I hit it off with the President of the Republic, who was born in Spanish Point, off the coast of which the galleon "San Marcos" had sunk. His wife Maeve had studied at the ICD and both were sympathetic to Spain. He invited me to visit his village, which I did with my wife Mavis, hosted by the presidential couple. Hillery told me he had a flat in Torremolinos where he spent his holidays and said he wanted to learn our language so he could talk to the policemen who served as his escort. I offered to give him lessons and, under this pretext, we met from time to time for lunch "incognito" at the Presidential Palace or at the Embassy residence.

The Minister for Industry, Des O'Malley, invited me to Limerick to attend the annual Cultural Weekend in honour of the writer Kate O'Brien, who had gone to Spain as a young girl as a governess in the Areilza family's house, became attached to the country and wrote a biography of Saint Teresa and several Spanish-inspired novels such as "Mary Lavell", "Farewell Spain" and "That Lady". In 1989, the conference was on "Kate O'Brien's links with Spain", in which I gave the inaugural lecture and José María de Areilza - whom I invited to the residency - gave the closing lecture on "A literary and personal portrait of Kate O'Brien". There was also a seminar on "Literary connections between Ireland and Spain", a reading of Spanish poems by the poet Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill, a recital of Spanish songs by Eithne Ni Uallachail and a concert of Spanish music by the guitarist Michael Smith. The following year's event featured the Spanish version of "Mary Lavelle", translated by UCD Spanish teacher Maribel Folley.

During my four years as ambassador, the sculptor Eduardo Chillida and the architect Rafael Moneo, the musical groups "Atrium Musicae", "Taller Ziryab" and "Alia", the pianists Joaquín Achúcarro, Enrique Pérez de Guzmán and María Garzón, the harpist Marisa Robles, the guitarists Miguel Bibiloni, Pablo de la Cruz, Ignacio Rodés and Agustín Maruri - in the concerts in honour of Segovia -, the singers José Carreras, Victoria de los Ángeles, Leopoldo Rojas, Josefina Arregui and Pedro de la Virgen, and the Flamenco Dance Group of Adolfo de Castro. The owner of the chalet where the ICD was located refurbished the semi-basement floor and a large space was installed in it, which we pompously called "Sala de Arte'92", where conferences were given and exhibitions such as "El sueño de Andalucía", "Sinografías", "Arte y Trabajo", "Colores", "Granada", "Spanish Paintings" or "Escultura multiplicada" were held. The Institute created the "Tomás Luis de Victoria" Choir - directed by June Broker -, founded, in collaboration with "Poetry Ireland", the "Antonio Machado Poetry Circle" - whose inaugural recital was given by Jorge Padrón - and sponsored the publication of Iain Mattew's book "Poems of the Spanish Mystics".

The icing on the cake of the cultural action "gratis et amore", by means of the "cultural sablazo", was the organisation of an exhibition on "Spanish avant-garde painting and sculpture". In 1989, my colleague Álvaro Fernández-Villaverde - who was in charge of international relations at Banco Hispanoamericano - and other senior officials of the bank visited Dublin and I invited them to lunch at my residence. When I heard about the Bank's great wealth of paintings, my alarm light went on and I asked Álvaro if the institution would lend the Embassy some of its works to hold an exhibition in Dublin. He told me that he would check with senior management and the answer was yes. The BHA provided the works, the Ministry paid for the insurance of the paintings and Iberia for their transport, the Irish Administration provided the Kilmainhan exhibition hall, and the Allied Irish Bank co-sponsored the event with the BHA and covered all the installation costs, thanks to my friendship with its chairman, former European Commissioner Peter Sutherland. The brand new President of the Republic, Mary Robinson, opened the exhibition, which was one of the cultural highlights of the year, without costing the Embassy a penny. These were just a few of the many cultural activities carried out by the Embassy and the ICD, but neither the Instituto Cervantes - which absorbed the latter - nor the Embassy in Dublin have had the good fortune to celebrate their anniversary.

Creation of the Instituto Cervantes

In 1989, the Spanish Government decided to create the Instituto Cervantes (IC), following the model of other similar institutions such as the British Council, the Alliance Française or the Goethe Institut, without asking for the opinion of the Embassies or the existing Cultural Institutes. At the end of 1990, we received the draft Constitutive Law of the Institute, the Report and the Curricular Design, together with a letter from the Director General of Cultural Relations requesting the opinion of the Embassy. As Law 7/91 had come into force on 23 March, there was no point in commenting on its content, so I confined myself to drafting some "Reflections on the constitution of the Instituto Cervantes and its impact on the Embassies", which I sent on 4 and 15 April in letters to the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Francisco Fernández Ordóñez, and the Minister of Culture, Javier Solana - who replaced him shortly afterwards - in which I warned them of the shortcomings of the Law and of the negative effects it could have on the Missions abroad, as well as of the urgent need to take appropriate measures during the transitional period to overcome them by drafting its Regulations. According to the Report, the IC Directorate's mission was to "plan, design, coordinate and implement the cultural activities to be carried out in the different Cervantes Centres, in coordination with the latter and with the competent ministerial departments". Nothing was said about coordination with the diplomatic and consular missions, which were also entrusted with cultural activities. On the other hand, it seemed that the ICE would be absorbed by the IC, but nothing was said about when or how, despite the fact that the 1991-1992 academic year was to be planned.

The Law prioritised the educational function of the Institute over the cultural one. Thus, it mentioned among its aims, firstly, "to promote universally the teaching, study and use of Spanish" and, secondly, "to contribute to the dissemination of culture abroad" (Article 2). The IC was attached to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but nothing was said about how this attachment should work or how external action should be carried out. This lacuna would have particular relevance for relations between the Institutes and the Missions abroad. Although the IC was a public entity, its activities should be governed by private law, but a non-profit institution under public law, presided over by the King and whose aim was to promote and disseminate Spanish language and culture throughout the world, should not be managed as a private commercial enterprise. The adjustment of its activities to the private legal system meant that the Institutes abroad were located outside the Spanish Missions, which entailed the non-application of diplomatic status to their staff, the obligation to pay taxes, submission to the regulatory diversity of each State, the application of rules designed for the operation of commercial for-profit entities, and the renunciation of the institutional cover of the Embassy for the carrying out of cultural activities. The provisions on the status of IC staff were succinct, vague and insufficient, and created an atmosphere of legal uncertainty. In my Report, I asked what was the formula foreseen for their incorporation, their contractual regime, their affiliation to the Social Security or the applicable law. No provision had been made and the staff of the IC was subject to the rules of the State in which they would carry out their duties.

The Law granted the IC very broad powers for cultural action and left little room for the diplomatic and consular missions, so there was a risk of interference between the two institutions, as the competences of the two were not clearly delimited.

IC officials visited the ICD and considered that its premises were not in keeping with the "'grandeur" that the new Institute was aiming for and said that a new site should be found in a landmark location in Dublin. The lease was due to expire the following year and we were told not to extend it. Fortunately I ignored them, because then the guy from the Treasury came along with the rebate, and the expected budget manna was considerably reduced. The IC absorbed the ICD and belittled its work, believing that it had to start from scratch as if, until its arrival, there had been no educational or cultural activity in Ireland. This attitude explains his refusal to celebrate the ICD's 50th anniversary. To each his own!

José Antonio Yturriaga, Ambassador of Spain, Professor of Diplomatic Law at the UCM and member of the Andalusian Academy of History.