The Impact of Assad’s Fall on the Tehran-Damascus-Algiers Axis

Since the outbreak of the Syrian war in 2011, Bashar al-Assad has received massive support from Iran, as well as military and diplomatic backing from Algeria. The Polisario Front, a separatist movement operating in the Sahara region and supported by Algeria, Iran, and Hezbollah, even sent armed elements to support Syrian regime forces.

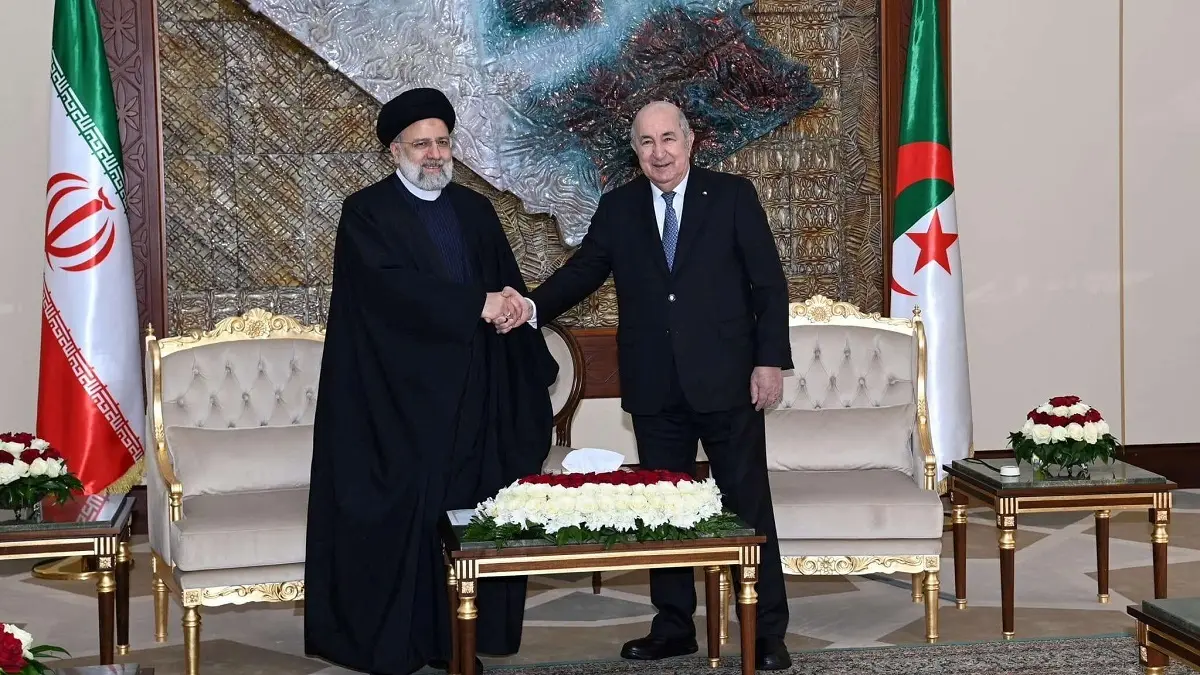

This Tehran-Damascus-Algiers axis is built on a convergence of geopolitical, ideological, and strategic interests, notably a resolute opposition to the West and a shared objective of countering moderate, pro-Western, and economically prosperous Arab states such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Morocco.

The regimes within this axis are also characterized by their propensity to implement heavy-handed, even repressive, policies in response to internal popular protests. Iran is infamous for its waves of arrests and systematic repression, exemplified recently by the crackdown on the anti-hijab movement sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini. Similarly, Algeria experienced a “black decade” following the 1992 coup, plunging the country into a civil war marked by severe human rights abuses. More recently, the Algerian regime suppressed the Hirak movement, which began in 2019, by imprisoning its leaders and targeting dissidents and journalists.

As for Assad’s regime, it stands out as one of the most repressive in the world. Beyond the destruction of Hama in 1982 to quell a Muslim Brotherhood uprising, the regime violently suppressed Syria’s 2011 uprising, characterized by mass arrests, systematic torture, and the use of live ammunition against civilians. Alleged chemical weapons use, such as in Ghouta in 2013, prolonged sieges, and bombardments of cities like Aleppo and Homs have caused famine and immense suffering among civilians. Forced disappearances and arbitrary executions in notorious prisons like Saydnaya further illustrate the regime’s brutality.

This axis, defined by centralized power and often repressive policies, poses challenges to regional stability and the democratic aspirations of its populations. The fall of one of its pillars, such as Assad’s regime, could reshape regional dynamics and weaken dependent movements, such as the Polisario Front.

For Iran, Assad’s fall would mean losing a strategic foothold on the Mediterranean and a key player in its confrontation with Israel and the United States. Syria has acted as a buffer against direct assaults by adversaries and as a corridor to Lebanon for Hezbollah, enabling the transfer of Iranian arms and equipment to its logistical bases. Already weakened by Israeli strikes in Lebanon, Syria, and even Iran, Tehran views the loss of such a loyal ally as a significant blow. Without Assad, Iran’s ability to rely on allied groups and regimes to propagate Shiism and impose a Tehran-dominated regional order would be severely diminished.

For Algeria, isolated on the Arab and North African stage, it has long relied on anti-Western authoritarian regimes like Iran and Syria to support its ambitions in the Sahel and North Africa. Algeria is troubled by alliances between moderate, pro-Western countries with liberal economies and evolving political systems. This has driven its attempts to recreate a “rejection front” through its alliances with Hezbollah, Bashar al-Assad, and Iran’s mullahs.

Algeria also seeks support from these actors in its “cold war” against Morocco, particularly on two fronts: Western Sahara and influence in Africa. Regarding Western Sahara, Morocco has gained an edge by developing the region, attracting major investors, securing recognition of its sovereignty, and opening new consulates. Its “Atlantic initiative,” which also includes Sahelian landlocked countries, has caused anxiety in Algiers, prompting it to attempt creating a Maghreb Arab union excluding Morocco and Mauritania—an initiative that failed before it began.

In terms of African influence, Morocco has surged ahead, investing heavily in West Africa and the Sahel, leveraging the prestige of its monarchy and the agility of its public and private enterprises. In just a few years, Morocco has become one of Africa’s most influential nations. In contrast, Algeria faces setbacks with its neighbors in Mali, Niger, and Libya, in addition to its longstanding closure of land borders with Morocco out of fear of the latter’s growing economic strength.

This has driven Algiers to seek alliances with Iran, Assad, and Hezbollah to counter emerging African partnerships favoring Morocco. The weakening of Iran and the diminishing disruptive capacity of Hezbollah were already bad news for Algeria’s military regime. Assad’s fall delivers a final blow.

What will Iran and Algeria do without Assad? Nothing is clear: weakened, Iran is seeking an understanding with the West to avoid further Israeli strikes and U.S. sanctions. It can no longer invest in its “Shia crescent” or in the Sahel and North Africa, as Algeria had hoped.

Meanwhile, isolated Algeria can rely on its strategic ally, Russia; however, Russia itself is preoccupied with extricating itself from the quagmire in Ukraine. The discord between Russia and Algeria over the presence of Wagner forces in Mali adds another layer of complexity.

The fall of Assad is a heavy blow to the Tehran-Damascus-Algiers axis but presents an opportunity for democracy and human rights in the region. It could help reduce tensions and rebalance power dynamics in the Middle East and North Africa.

For Iran and Algeria, real internal change becomes inevitable. The question remains: will they have the capacity to adapt, or will they remain prisoners of their past choices?